In Ireland it has been common to hear left-wing nationalists claim that Marxists support the nationalism of oppressed nations.

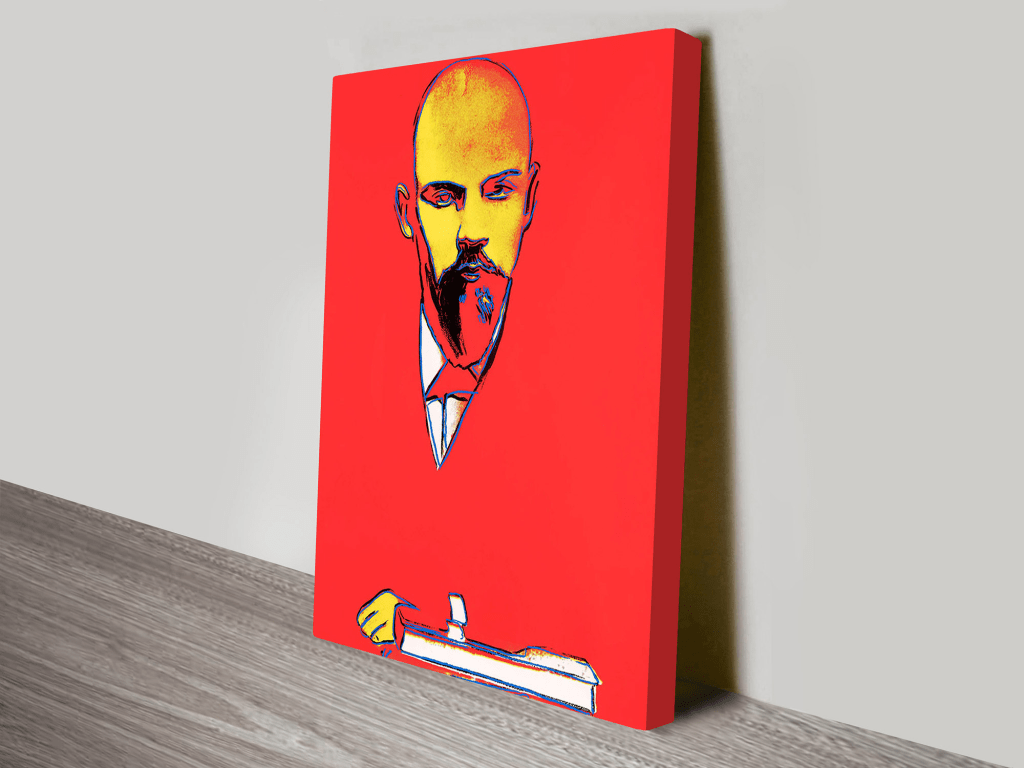

In ‘Critical Remarks on the National Question’, quoted in the previous post Lenin writes:

‘The principle of nationality is historically inevitable in bourgeois society and, taking this society into due account, the Marxist fully recognises the historical legitimacy of national movements. But to prevent this recognition from becoming an apologia of nationalism, it must be strictly limited to what is progressive in such movements, in order that this recognition may not lead to bourgeois ideology obscuring proletarian consciousness.’

‘The awakening of the masses from feudal lethargy, and their struggle against all national oppression, for the sovereignty of the people, of the nation, are progressive. Hence, it is the Marxist’s bounden duty to stand for the most resolute and consistent democratism on all aspects of the national question. This task is largely a negative one. But this is the limit the proletariat can go to in supporting nationalism, for beyond that begins the “positive” activity of the bourgeoisie striving to fortify nationalism.’

‘To throw off the feudal yoke, all national oppression, and all privileges enjoyed by any particular nation or language, is the imperative duty of the proletariat as a democratic force, and is certainly in the interests of the proletarian class struggle, which is obscured and retarded by bickering on the national question. But to go beyond these strictly limited and definite historical limits in helping bourgeois nationalism means betraying the proletariat and siding with the bourgeoisie. There is a border-line here, which is often very slight and which the Bundists and Ukrainian nationalist-socialists completely lose sight of.’

‘Combat all national oppression? Yes, of course! Fight for any kind of national development, for “national culture” in general? — Of course not. The economic development of capitalist society presents us with examples of immature national movements all over the world, examples of the formation of big nations out of a number of small ones, or to the detriment of some of the small ones, and also examples of the assimilation of nations.’

‘The development of nationality in general is the principle of bourgeois nationalism; hence the exclusiveness of bourgeois nationalism, hence the endless national bickering. The proletariat, however, far from undertaking to uphold the national development of every nation, on the contrary, warns the masses against such illusions, stands for the fullest freedom of capitalist intercourse and welcomes every kind of assimilation of nations, except that which is founded on force or privilege.’

So we see the progressiveness of nationalism, as the political framework for the development of capitalism against feudal restrictions, but not as support for capitalist states or their various nationalisms that develop thereafter. Thereafter, the development of capitalism creates a working class with the interests of this class the same across national borders and therefore opposed to the division of the class that nationalism entails.

Support for nationalism beyond the negative sense of opposition to national oppression is to capitulate to bourgeois nationalism. Support against national oppression is limited to what is progressive in any nationalist movement and although there may be a border-line between this and betraying the working class to bourgeois nationalism, what we have in the approach of much of the left today is an instinctive and automatic rush to reach for the policy of self-determination of nations in order to justify the decision to support one state in any particular conflict.

Lenin’s ‘formula’ of self-determination of nations has been carried forward as the key to unlocking any national issue without regard to its historical limitation and by ignoring Lenin’s explicit subordination of this justification to the determining interests of the working class.

Instead of the unity of the working class coming first, the demand for self-determination for a particular nation is placed beforehand, with the assumption that this leads to the former. Since the demand for self-determination is a bourgeois democratic demand it cannot even on its own terms be seen to lead to the unity of the working class. We have countless historical examples of self-determination being enacted through creation of new nation states with capitalist social relations and no progressive working class unity established.

Supporters of ‘Ukraine’ have, for example, said that ‘the people of Ukraine must be allowed to exercise freely their right to democratic self-determination, without any military or economic pressure’. This has been accompanied with calls to cancel Ukraine’s foreign debt – ‘it is important in ensuring that, when they have reconquered their independence, Ukrainians won’t be even more dependent on creditors or domestic oligarchs over whom they have no control.’

But we have demonstrated that the demand for self-determination is not only not applicable to an independent country like Ukraine in this war, but is a capitulation to bourgeois nationalism, with the long quote above demonstrating why.

As Lenin says – self-determination is not support for anything other than the right to secede and form an independent state, and in doing so to reject feudal or dynastic chains such as were forged by the Tsarist, Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires. This will allow for the free development of capitalism by that particular state. It is no job of socialists to uphold that state’s capitalist economic development that is built on the exploitation of workers, except in so far as we welcome this development by its creation of a working class that will overthrow it, and which more and more removes national differences. It is therefore, not our job to seek to constrain such development through reactionary political projects such as Brexit or splitting already established states, such as Britain.

When left nationalists welcome that ‘Ukrainians’ have ‘reconquered their independence’ but complain that foreign debt must be also be cancelled, so that they won’t be dependent on foreign creditors or domestic oligarchs, they fall exactly into the camp of bourgeois nationalism.

Firstly, the cancellation of past debt will without doubt be followed by incurring new debts, debts that will be paid from the surplus produced by Ukrainian workers who will not be free and independent of either this debt or the domestic oligarchs, who can only be disposed of through socialist revolution and not mitigation of foreign loans. It is no job of socialists to defend the capitalist development of smaller or weaker capitalist states as if they are somehow oppressed and exploited when the real exploitation involved is class exploitation.

While, on its own, socialists will not object to the cancellation of foreign debt (but why just foreign? what would these socialists demand if the debt was gifted to domestic creditors? ) this cannot be as part of support for a programme of capitalist economic development. To repeat, for us the development of capitalism is of benefit because it creates the working class, and its greater development objectively prepares this class for its historic task of becoming the new ruling class and undertaking the task of abolishing class altogether.

The capitalist development of new nations inevitably involves insertion into a world system that will rob the innocent of any illusion that their nation is really independent of the forces that determine its future. Overwhelmingly these forces are based on the interests of the most powerful states and the largest capitals. Just as big capitals destroy small ones within the framework of their own state, these capitals get too big for the nation state and seek existence across states, creating multinational capitals and multinational para-state bodies, which determine the fortune of smaller states and smaller capitals.

In attempting to counter such forces Lenin goes on to say that ‘Consolidating nationalism within a certain “justly” delimited sphere, “constitutionalising” nationalism, and securing the separation of all nations from one another by means of a special state institution—such is the ideological foundation and content of cultural-national autonomy. This idea is thoroughly bourgeois and thoroughly false.’

‘The proletariat cannot support any consecration of nationalism; on the contrary, it supports everything that helps to obliterate national distinctions and remove national barriers; it supports everything that makes the ties between nationalities closer and closer, or tends to merge nations. To act differently means siding with reactionary nationalist philistinism.’ This is the ground on which socialists oppose all varieties of nationalism and oppose reactionary national movements.

In one Facebook discussion a supporter of the Ukrainian state argued that self-determination required the ability of Ukraine to decide its own international alliances. When someone tries to argue that socialists should fight for the right of a capitalist state to join an imperialist alliance such as NATO you know you aren’t dealing with any sort of socialist, and certainly not arguing with support from Lenin’s formulation of self-determination of nations.

to be continued

Back to part 1

Forward to part 3

Karl Marx’s Alternative to Capitalism – part 34

Karl Marx’s Alternative to Capitalism – part 34 As we argued in the

As we argued in the  For some people, getting a simple majority in the North of Ireland is not sufficient to justify a united Ireland, and Taoiseach Leo Varadkar is not the first leading southern politician to question whether it would be enough. The unionist leader Peter Robinson has also said that any border poll on Northern Ireland’s future in the UK could not be conducted on the basis of a simple majority. Varadkar has said that an Irish unity poll would be divisive and “a bad idea”, that the idea of a “majority of one” would lead to chaos, and questioned whether it would be a “good thing”.

For some people, getting a simple majority in the North of Ireland is not sufficient to justify a united Ireland, and Taoiseach Leo Varadkar is not the first leading southern politician to question whether it would be enough. The unionist leader Peter Robinson has also said that any border poll on Northern Ireland’s future in the UK could not be conducted on the basis of a simple majority. Varadkar has said that an Irish unity poll would be divisive and “a bad idea”, that the idea of a “majority of one” would lead to chaos, and questioned whether it would be a “good thing”.

I have

I have  My daughter wrote in her Facebook page that “I’ve attempted to write how disappointed and shocked I am over the results and I just can’t put it into words.”

My daughter wrote in her Facebook page that “I’ve attempted to write how disappointed and shocked I am over the results and I just can’t put it into words.”