Volodymyr Zelensky has said that World War III has already started. If so, Ukraine is fighting it, supported by Western imperialism, which means that the ‘left’ supporters of Ukraine have already picked a side. From the point of view of opposing the further development of this war they are worse than useless.

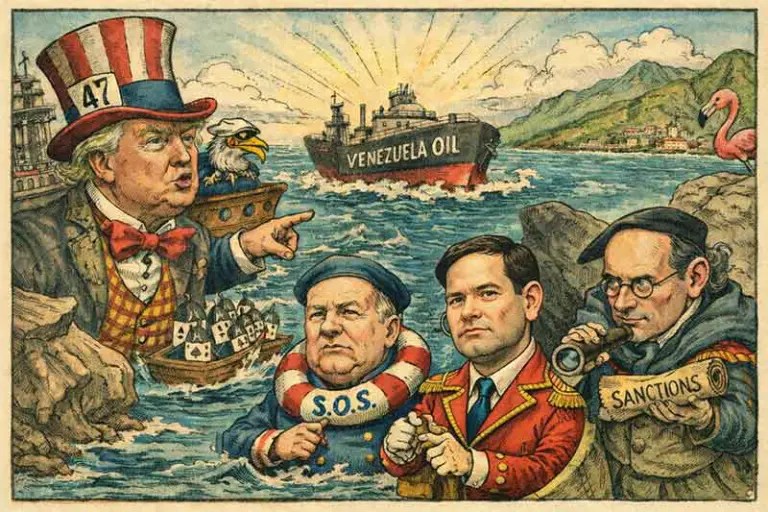

Its development includes attacks on Venezuela, and now once again on Iran. In the first day this involved the destruction of an elementary school, killing over one hundred young girls, barely acknowledged with a shrug and a lie, plus the sinking of an unarmed Iranian ship with its sailors left to drown. This is a war crime that even the Nazis adhered to at the start of World War II. As one commentator noted the US had “now dropped below that level.”

This statement would be true were the word ‘now’ removed. While each atrocity is treated as a singular act of barbarity with its own characteristics, it is unfortunately the case that this level is all too familiar. It is not only ‘now’ that US imperialism, its Zionist attack dog and the ‘civilised’ European states have involved themselves in atrocity. What is worse than a rolling genocide in which ‘peace’ is declared as a real estate project to build a golden holiday resort over the ashes of the dead?

The working class is constantly invited to compartmentalise the world into discrete and separate events that are unrelated, so that they are unable to understand or remember them as more than individual examples of immoral turpitude. The foreign policies of states are somehow different from domestic policy, one foreign policy has nothing to do with another, and what happened in the past stayed there.

The ‘left’ supporters of Ukraine excel in this–western imperialism is condemned in relation to Palestine and Iran while approved for support for Ukraine. It supports a Ukraine that supports the attack on Iran and states that it wants to be a “big Israel” in Europe. It now also seeks to provide help to the reactionary and authoritarian Arab states collaborating with the attack. Yet the pro-Ukraine left justify their position by claiming a war between democracy and authoritarianism.

The authoritarian policies of Trump and Starmer demonstrate what a deception it is to provide political support to any imperialist state. Inconsistent opposition to imperialism can only be justified by claiming that imperialism itself is inconsistent: not an irradicable feature of capitalism but a choice that sometimes means imperialist war is progressive.

Authoritarian politics inside the West is directly related to its foreign wars. This is evidenced in country after country: Starmer treats anti-genocide protesters as terrorists; the German state represses Palestine supporters, and Trump unleashes State paramilitaries on the working class while elected not to engage in foreign wars.

In Ukraine, credentials for the good fight against authoritarianism include the ban on opposition parties and media; martial law; the ‘busification’ of men into the army; the conscription of the working class and poor while the sons of the rich and connected are free, and millions seeking escape to avoid the draft.

In Ireland, the Irish bourgeoisie trumpets its anti-colonial history while the state has become an integral part of imperialism. Shannon airport has become an important hub for US supply of war material to Israel; the Irish Central bank has facilitated the sale of Israeli bonds that have helped finance the genocide, and booming trade with Israel has made it that state’s second biggest trading partner.

The Irish pretence at neutrality is increasingly an obstacle to the state’s international political role aligning with its economic. This is why the ‘threat’ from Russia, like everywhere else in Europe, is paraded as justification for massive rearmament with the objective of joining NATO. The Irish left defends ‘neutrality’ and opposes joining while much of it supports Ukraine’s war for NATO membership and the arming of it by the alliance.

Western hypocrisy in relation to the attack on Iran finds refuge in its denunciation of the repressive character of its state while the Western media fixates on questions of the purpose and endgame of Trump’s attack. The crazed and criminal intentions of the Zionist state are simply reported as a natural and accepted condition of that state, which of course is true, but without the moral approbation it would normally entail.

The dismay among media commentators that there is a complete lack of strategy in Trump’s actions, and no endgame ,fails to understand that war is itself a strategy, albeit an inadequate one, and that the inter-imperialist rivalry that lies behind it does not have an end outside of human catastrophe or an end to imperialism itself.

We have seen one attack on Iran end without resolution and there may be another. The weakening of it can be expected to continue in any event, as one aspect of exerting US power against China and its Russian ally. The remaining power of the US is displayed both by its attack on Iran together with the relative weakness of the Russian and Chinese responses, alongside the extreme reluctance to ‘put boots on the ground’, and the analogous but opposite situation in Ukraine.

The endless horror of war requires greater censorship and repression at home. The Russian invasion cannot be mentioned without it being called ’unprovoked’, ignoring the obvious provocations by NATO and Ukraine, while the word ‘unprovoked’ disappears from the dictionary when describing the attack by the US and Israel on Iran.

This is obvious propaganda. It has largely succeeded in relation to the war in Ukraine but not regarding genocide in Gaza, and many can also see the hypocrisy involved in the attack on Iran. It doesn’t translate into opposition because there is no pre-existing political opposition to imperialism that can navigate the cascading conflicts and present an alternative, although this is simply to declare the current weakness of socialism.

We have already noted the stupidity of much of the Irish left in opposing the push to Irish NATO membership but supporting the Ukraine war for it. The rest of the Western left supporting Ukraine must explain how it can oppose imperialist rearmament while calling for more weapons to Ukraine that require it. Why doesn’t it support Russian arms to Iran since it is the subject of an unprovoked attack by imperialism? That way it could demonstrate its otherwise ridiculous claim not to be ‘campist’ by supporting the US against Russia in Ukraine and Russian against the US in Iran. Instead of opposing both it could achieve this feat by the truly remarkable device of supporting both!

The propaganda succeeds because the invasion should be opposed but not by supporting the Ukrainian state in its alliance with western imperialism, which began before the invasion. In addition, the Iranian regime is brutal and reactionary, but US imperialism has paraded its callous cruelty with bombastic pride since the start of its attack. Without a working class perspective there is no third force or policy to consistently pose a coherent response.

The petty bourgeoisie, with moralistic beliefs, is incapable of overcoming in politics the limitations of its social position that reduces social questions to good versus bad without any deeper social critique. No understanding can arise from it of the differences between the Ukrainian state, its people or its working class and that they should be considered to have separate and opposed interests. When the Ukrainian state unites with imperialism; its corruption involves its bourgeoisie siphoning off millions of dollars of aid; when it attacks working class people in the street to cart them off to the front; when it celebrates the fascist units in its armed forces–all this does not fit the desired narrative of a good victim, so is effectively ignored.

In Iran, the perceived need not to ‘complicate’ the narrative leads to reluctance to separate the interests of the Iranian state and its regime from that of the Iranian people and its working class. Yet the reality that they are not the same was proved by the regime killing thousands of protesters only a couple of weeks ago. The idea that these were all Mossad agents shows only the susceptibility of many to the view that only the Iranian regime and its imperialist enemy matter. That opposition to one means support for the other. Yet the future of Iran and its people depend on this not being true.

For many on the left old formulas of ‘self-determination of nations’ and ‘anti-imperialism’ show only that they seek to hit a target but miss the point. The socialist movement has witnessed many imperialist wars, and it is now some time since they held up the banner of socialism as the only way to stop them.