It’s always been said that if you’re going to tell a lie, tell a big one. The more outrageous the better. It immediately requires a big denial that itself feels like it is making a big claim. A big lie also has numerous and wide consequences, so denial equally requires a lot of follow-through.

For many people the social opprobrium of denial is enough to impose silence and there are lots of incentives to keep schtum, including entreaties to ‘be kind’, be ‘on the right side of history’, not to be a bigot – or what seems to work better – not have anyone call you one. And so many people on ‘your side’ seem to go along with it, and so many not on ‘your side’ seem to be against. Anyway, it all involves a small number of people so let’s not get exercised about it.

An additional factor is the temptation not to think too hard about it all, lest you end up having the debate in your head that you have been insistently told you can’t have outside it. The ‘no debate’ mantra of some trans activists thus functions at two levels. It immediately fences off from acceptable discussion disagreement with the view that men can become women – and in doing so claim all their rights – and treats such disagreement as akin to racism or homophobia. The assertion itself is therefore free from questioning.

Since there is now a fashion for the introduction of hate crimes in certain countries, the subjective views of those carrying out alleged criminal acts are also taken into account; meaning that what you think can also be taken as an aggravating factor and in effect become an ancillary crime itself. We are not quite in ‘thought-crime’ territory but we are definitely in the land of ‘impure thoughts’, so you must not only do as you are told but believe it as well.

I have written before that this ‘no debate’ mantra is the cause of the ‘toxicity’ of the (non) debate, so is largely the result of the virulence of tans activism. Of course, this is a product of the preposterous nature of the claim itself but the consequence of this combination – of the outlandish claim and command to agree – results in the anger of those critical of the claim, and their exasperation at those who just want to ignore it, or turn a Nelsonian eye to the whole thing.

Again and again, however, the ideology hits you in the face, with the claim to be a uniquely vulnerable and marginalised minority clashing with the obvious support accorded to it by the state and other institutions. Often, when it does, it’s because the consequences of the claim once again conflict with reality.

Let’s take an example I came across in the past week.

My wife was asked to complete a survey originating from Kings College in Britain, the purpose of which was stated as follows:

‘We would like to invite you to participate in this online survey which will explore how anxiety, emotion and wellbeing are experienced in the body after primary breast cancer and in secondary breast cancer. Before you decide whether you want to take part, it is important for you to understand why the research is being done and what your participation will involve’

‘We know that many people struggle with their mental health after primary breast cancer and in secondary breast cancer. Breast cancer and our emotions are also both rooted in the body. However, research has not yet explored how people feel emotions in their body during and after breast cancer, and how this can impact people’s general wellbeing.’

The survey is designed to take about 30 minutes, so not a quick on-line poll: ‘The purpose of the study is to understand how interoceptive sensibility – how someone feels able to sense their internal bodily sensations – impacts people’s experiences of mental health and wellbeing after primary breast cancer and in secondary breast cancer.’

By way of context, Cancer Research UK records that there are around 56,800 new breast cancer cases in the UK every year and that it is the most common cancer in females with around 56,400 new cases every year (2017-2019) but not among the 20 most common cancers in males, with around 390 new cases every year (2017-2019). This translates into an annual death toll among women of 11,415 and among men of 85 with a mortality rate of 33.9 and 0.3 respectively. This means that women account for over 99 per cent of deaths from breast cancer.

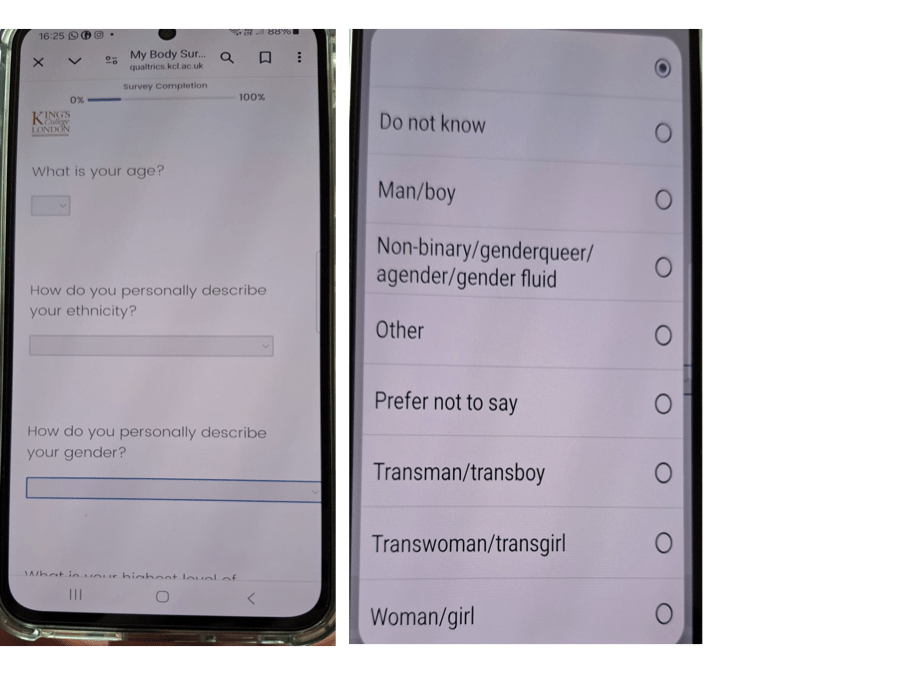

So, if men can also suffer from breast cancer and it is not a women-only disease, perhaps we can accept the use of the word ‘people’ in the survey from Kings College. What is hard to accept is one of the questions at the start of the survey, which I captured on my phone and the range of potential answers expected and requested:

Question and permitted Answers:

If we were to be (very) charitable, we might say that the survey is about subjective responses to having had or still having breast cancer and that it is a valid objective to distinguish, and then compare, the subjective response of women, men and trans individuals. The permitted answers forswear the outer reaches of trans ideology by lumping together a number of ‘identities’ and excluding the myriad of others of uncertain number.

In doing this however, we would have to ignore the biological basis of cancer and that the overwhelming risk attaching to it is not ‘gender’, whatever that is, but sex. We would also have to pass over the recognition by the survey’s authors that the study already recognises the primacy of biology by stating that ‘Breast cancer and our emotions are also both rooted in the body’ and that ‘The purpose of the study is to understand how interoceptive sensibility – how someone feels able to sense their internal bodily sensations. . .’

The problem is that the question is designed to find out not only what ‘gender’ someone thinks they are but what sex they are, and if someone were to reasonably state that non-binary/genderqueer/agender/gender fluid are not a sex then the question is at best ambiguous. At worst it is an invitation to accept gender identity ideology; that all the answers are equivalent and gender = sex and there are more than two. If you don’t accept this equality then you would be entitled not to answer the question on the grounds that you do not have a gender identity.

In this case, from any scientific perspective, the survey is flawed. And in any case, anyone studying the responses who thinks ‘I don’t know’ is a valid answer to the question ‘how do you personally describe your gender’ has a big problem. Is the respondent stupid, confused or does she or he think that the question is stupid or the result of confusion?

Occam’s Razor would lead one to the conclusion that the survey is an example of gender identityideology positing the salience of self-ID to the feelings of women who have or are suffering from cancer. Does this matter?

This is often the question used to puncture opposition to expressions of gender identity ideology. In this case the scientific soundness of the survey is called into question by mixing incommensurate concepts. The introduction of the survey, on the stresses of having cancer, to be read by participants before they complete it, is keen to avoid causing further stress, advising ‘that you contact your GP in the first instance.’ One wonders how a question relating to a disease that by over 99 per cent affects women could put this category at the bottom of eight when attempting to identify its public.

Perhaps this will also be excused as a mistake, but that would be to deny the claims of gender identity ideology for which such a question is totally appropriate and absolutely necessary. Don’t ask why, because that is to presume an explanation that itself presumes reasoning that itself must be open to interrogation, and that would require a debate.

Back to part 4

Forward to part 6