I remember giving out leaflets at a Sinn Féin demonstration on the Falls Road in about 1993. The demonstration was called to support the Hume-Adams Agreement, hammered out between the leaders of the SDLP and Sinn Féin after several secret meetings. No one knew what was in the Agreement, but thousands of republican supporters came out to show their support for it.

I don’t think my comrades, or I, ever had such a keen and eager crowd as the demonstrators queued up to get a copy. It was clear that they thought they might find out what it was they were demonstrating in support of. That in itself told us an awful lot about the political consciousness of rank and file republicans at the early stages of the peace process – they were going to faithfully follow their leadership, wherever it led them and swallow whatever they were told.

Many, many subsequent leaflets, and meetings through the long peace process changed nothing of their approach, or raised in them any consciousness that they might require a more critical approach, one that involved some scepticism of where their leadership was taking them.

Only a few years before, in 1987, Sinn Féin had published a document called ‘A Scenario For Peace’ in which it set out its proposals for a settlement to end the conflict. It included that Britain should declare its intention to withdraw; the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Ulster Defence Regiment would be disbanded; ‘political’ prisoners should be unconditionally released; and Britain should provide a subvention for an agreed period to facilitate harmonisation of the northern and southern economies. In return, unionists would be offered equal citizenship within the new Ireland.

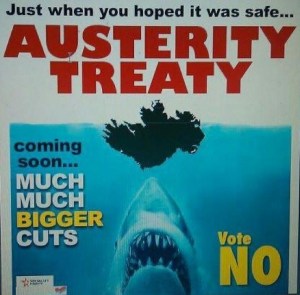

Well, the Hume-Adams talks were not about this agenda, and neither was the peace process. The British have not gone, the RUC and UDR were indeed disbanded but the former was replaced by the PSNI and the latter were a unit of the British Army, and it certainly hasn’t gone away. Political prisoners were released but not unconditionally, Britain imposed austerity (and Sinn Féin helped implement it).

The peace process in its various guises is now longer than the war it was supposed to end, and the former looks harder to get to the end of than the latter did. When it was announced that the devolved Stormont Assembly was coming back, and a Sinn Féin leader, Michelle O’Neill, would be first minister, it was declared by Mary Lou McDonald that this showed that a united Ireland was “within touching distance”. Of course, the Provisional republican movement has been promising a united Ireland since the early 70s, that is, for over half a century. A unionist commentator noted recently that a recent opinion poll showed no increase in support for a united Ireland in the North over the last couple of decades.

Some columnists have claimed that the real significance of the return of the DUP to the Assembly and Government is this accession to the post of first minister of Sinn Féin, even while they admit that this is symbolic since the unionist deputy first minister has equal power. No decision can be taken by the first minister if not agreed by the deputy and the post cannot be filled in the first place without unionist agreement.

In order to minimise unionist opposition to the deal between the DUP and British government over the ‘Irish Sea border’ the process of getting DUP agreement and all it entails is being rushed through. The DUP Executive thus voted for the deal without seeing it; fittingly appropriate to the return of what passes for democracy in the North of Ireland.

This democracy, in the shape of the Stormont Assembly, has been suspended at least eight times, ranging from a single day to a couple of years. It has been functioning for only sixty per cent of its existence and subject to a number of reviews and changes with yet more changes now widely canvassed. The sectarian, corrupt, incompetent and clueless governance it has provided and the future problems considered inevitable by everyone who thinks about it (and many don’t) means that the rules are not the problem.

Public services, from health to roads, are routinely described as being in crisis, while others such as education and voluntary organisation are subject to open sectarian practices. It has been claimed that these issues can only be put right by local governance, but its track record shows that it is as much responsible for the decay as British rule. The repeated suspension allows the alibi to be sold that were it not for suspension public services would be much better. The previous suspension following the Sinn Féin walk-out, after the DUP-implicated Renewable Heat Incentive scandal, showed levels of incompetence that could more easily be explained as corruption.

The return of Stormont is therefore no step forward, never mind a panacea, and is mainly an unstable framework to accommodate sectarian competition, one that has not proved to be very stable. It stands on its rotten foundations only because there is no outside force to push it over, while those that have knocked it over temporarily have been internal. It is widely accepted among the population and further afield because no alternative seems possible, which is why the DUP have gone back in. This also helps explain why the misgivings of many unionists, and significant opposition, will be unsuccessful in stopping the Assembly’s return.

The opposition has no credible leadership, which would have to come from within the DUP itself, and there is as yet no real sign of this. Further demoralisation of unionism is therefore one (welcome) result.

That this is the case throws light on the claim by the DUP leadership that their new deal is a significant victory. Packaged as a joint British government/DUP initiative, and launched by a joint press conference, there is not the slightest pretence at non-partisanship by the British: ‘Safeguarding the Union’ is the name of Command Paper1021.

Its content in 77 pages could safely be accommodated at one tenth of the length. The measures introduced include proposed legislation to say that Northern Ireland is part of the UK – who would have thought it? It has proposed legislation to ‘future-proof the effective operation of the UK’s internal market by preventing governments from reaching a future agreement with the EU like the Protocol’, which by definition cannot achieve what it claims. It also includes a ‘commitment to remove the legal duties to have regard to the “all-island economy” in section 10(1)(b) of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.’ A bit of red meat for the DUP, and sticking it to Irish nationalism North and South, that will make little or no difference.

It promises that ‘Legislative change to recognise the end of the automatic pipeline of EU law . . . which applies in Northern Ireland is now properly subject to the democratic oversight of the Northern Ireland Assembly through the Stormont Brake and the democratic consent mechanism.’ This implies either future bust-ups with the EU if single market changes are not incorporated into the Northern Ireland market, or a formality to cover regulatory alignment. The Brexiteers in Britain are aghast at this as they no doubt realise it might not be the former.

Media reporting has suggested that the EU Commission has yet to look at the Agreement but that ‘no red lines’ have been crossed; however, it is hard to believe it has not been agreed and only kept quiet in order to help the DUP sell it as an act of undiluted British sovereignty.

The ‘democratic consent mechanism’ that is held to act as a check on unwelcome EU encroachment states that it can be triggered by a majority of local members of the Assembly and not by some ’cross-community consent’ mechanism. It is hard to be optimistic that this whole area will not entail future argument.

Other measures include promises on maintaining trade flows that can’t be honoured and a number of new quangos that will deliver more red tape that Brexit promised to get rid of.

The main gain pointed to by Jeffrey Donaldson is the removal of routine checks on certain exports from Britain to Northern Ireland that were set to reduce anyway but are now declared to be zero. This is on goods, such as retail to consumers for example, that will stay in Northern Ireland and not considered to be at risk of going further into the Irish state and thus the EU single market proper.

Donaldson has, however, claimed too much – that there is unfettered trade between GB and NI and therefore no sea border. The command paper states that ‘there will be no checks when goods move within the UK internal market system save those conducted by UK authorities as part of a risk-based or intelligence-led approach to tackle criminality, abuse of the scheme, smuggling and disease risks.’

‘Abuse of the scheme’ must mean that checks will be made if it is suspected that goods purportedly sent for sale only in Northern Ireland are actually heading further. The acceptance of such controls by the DUP has so far been rather successfully sold by the leadership as simply a common sense measure that ensures that checks are made at the Northern Ireland ports instead of a long and windy North-South border.

This problem arises only because of Brexit, which the DUP supported, and of course the argument makes sense in its own terms; except those terms mean acceptance that there is a trade border on the Irish Sea because there had to be one somewhere, and its not south of Newry and north of Dundalk. The opponents of the Agreement among unionists are therefore right that single market membership means EU law applying in Northern Ireland. They go wrong when they, like the other hard Brexiteers, assume that the British government must pursue widespread non-alignment, without which Brexit makes even less sense that it already does.

In the last few weeks public sector workers in the North have engaged in very large strike action in pursuit of wage demands designed to recover some of their lost real incomes. It has, however been subsumed under the politics of Stormont return, even while the trade unions have demanded that the British Government pay up and not use the lack of an Assembly as an excuse. It was supposedly putting pressure on the DUP to get back so the workers could get payed when the DUP didn’t, and doesn’t, give a toss.

The return of Stormont has not been lauded and celebrated as in previous ‘returns’ and the population is jaded by repeated failure and broken promises of a ‘new approach’. The real new approach required is, unfortunately, a long way off.