![rr06[1]](https://irishmarxism.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/rr061.jpg?w=584&h=386) In my review of the programme put forward by the left in Ireland, generally no different from other countries across Europe and further afield, I have argued that while it may be better for workers than the current austerity policies it is not socialist. By this I mean that it does not involve a class alternative, an alternative to capitalism, one that involves ownership of the means of production moving to the working class.

In my review of the programme put forward by the left in Ireland, generally no different from other countries across Europe and further afield, I have argued that while it may be better for workers than the current austerity policies it is not socialist. By this I mean that it does not involve a class alternative, an alternative to capitalism, one that involves ownership of the means of production moving to the working class.

Only in one area is this not the case: the Left’s occasional demand for workers’ control. Even in these cases I have argued that the proposals are not put forward within any real practical perspective but put forward in such a way that they must assume a near revolutionary situation. Demands for widespread workers’ control are only a practical proposition in such circumstances.

In current conditions demands for workers’ control simply demonstrate a lack of seriousness by those proposing them. In the article by Trotsky previously quoted, he states that “before this highly responsible fighting slogan is raised, the situation must be read well and the ground prepared. We must begin from below, from the factory, from the workshop.”

This is to be done by revolutionaries gauging the moods of other workers – “to what extent they would be ready to accept the demand to abrogate business secrecy and to establish workers’ control of production. . . . Only in the course of this preparatory work, that is the degree of success, can (we) show at what moment the party can pass over from propaganda to further agitation and to direct practical action under the slogan of workers’ control.”

“It is a question in the first period of propaganda for the correct principled way of putting the question and at the same time of the study of the concrete conditions of the struggle for workers’ control.”

One small means of doing this recently was, when the banking crisis erupted, members of Socialist Democracy leafleted bank workers in Dublin asking them to let other workers know what was going on in the banks through leaking internal emails etc. This small step abrogating business secrecy is a first step to workers’ control. The poor response showed that the preparatory work described by Trotsky had yet to begin.

In this post I want to look at what is meant by workers’ control and how this is a result of the working class’s historical experience of this means of struggle. The experience shows that it inevitably arises as a result of a crisis, and crises are by their nature temporary, occasioned by a society-wide political crisis or by the threatened closure of a particular factory that is producing unnecessary products, is working in an obsolete manner or is otherwise failing to compete successfully in the capitalist market.

How to institutionalise such control in periods of relative calm is a central problem we will look at in future. Relying on temporary crises to quickly provide workers with answers to the problems posed by their taking control has not resulted in success. Revolutions of themselves do not give all the answers to the problems posed by revolution, at least not unless they are prepared for and prepared for well. Since revolution is the task of workers themselves we are talking about how they can be prepared to take on the tasks of control. Such preparation involves convincing at least some of them them that they should want to control or manage their own places of work as well as how they might be able to do so. Only in this way can the superiority of worker owned and managed production be demonstrated.

The historical understanding of what workers’ control means derives mainly from the experience of the Russian revolution in 1917; the only successful workers led revolution. Yet the goal of this revolution was initially a democratic republic, not a workers’ state, with the result that only a ‘transitional’ social and economic programme was on the agenda. A decision to seize power by the Bolshevik Party could not change the level of economic and social development in itself. We can see from an earlier post that this informed Lenin’s view that the immediate economic programme was one more akin to state capitalism than complete working class ownership and power over the economy.

This is decisive in understanding the development of the revolution. The workers could seize state power in order to stop the war, support distribution of land to the peasantry and attempt to put some organisation on production but workers could not by an act of will develop the Russian economy under their own control and management, at least not outside of a successful international revolution, and this never came.

Workers’ control in such a situation did not, and at least initially could not, equate to complete management. In Russian ‘kontrol’ means oversight; a “very timid and modest” socialism, as the left Menshevik Sukhanov put it. The Bolsheviks understood that workers’ control was not socialism but a transitional measure towards it. Capitalists would and did continue to manage their enterprises. (The historian E H Carr reported that in some towns workers who had driven out their bosses were forced to seek their return.)

This approach was supported by the factory committees created by the workers during the revolution. These committees initially hardly went beyond militant trade unionism but did not accept management prerogatives as inevitable and, as the bosses increasingly sabotaged production, they increased their interventions to take more radical measures of control.

The workers nevertheless saw the solution to their problems as soviet power and state regulation, evidence by their acceptance of a purely consultative voice in state-owned (as opposed to privately owned)enterprises. This reflected the worker’s weakness, expressed by one shipyard worker on the eve of the October revolution at a factory committee conference: “often the factory committees turn out to be helpless . . . Only a reorganisation of state power can make it possible to develop our activity.” Thus much of the activity of the factory committees was attempting to find fuel, raw materials and money simply to keep factories going and real management was sometimes consciously avoided.

Trade union leaders criticised the factory committees for only looking after the interests of their own plants and for not being independent of the capitalists who owned them. The workers in the committees were themselves keenly aware of being compromised by the capitalist owners, of being given responsibility without effective power.

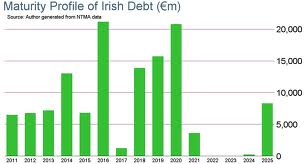

While the revolution was supposed to have a transitional character in economic terms, workers were faced with greater and greater sabotage and recognised that the worsening crisis required a solution that could only come from the state, which would provide the centralised control that would combat economic dislocation. The weakness of the workers themselves can be quantified by the decline in their number. In 1917 the industrial workforce in Petrograd was 406,312 but fell to 339,641 by the start of 1918 and only 143,915 by May of that year.

Although more active forms of workers’ control were sanctioned after the revolution, it had been increasing anyway, the steps towards the central state regulation that had been championed were constrained by the lack of an “organised technical apparatus, corresponding to the interests of the proletariat”, as the resolution unanimously adopted by the January 1918 Factory Committee conference put it. Nevertheless the conference called for the immediate nationalisation of factories in a good physical and financial situation.

The economic situation however was desperate as the new state faced immediate armed attack. The Factory Committee conference noted that: “Every one of us knows that our industrial life is coming to a standstill and that the moment is fast approaching when it will die. We are now living through its death spasms. Here the question of control is no longer relevant. You can control only when you have something to control.”

Widespread nationalisation was introduced but it was viewed as a necessity compelled by circumstances, not a positive choice and not one driven by socialist ideology. Alongside this nationalisation was increasing centralisation of economic decision making, which was imposed on the factories.

But of course if the workers were unable to run the factories how could they run the state? Complaining that the factory committees were ignoring everything but their own local interests and themselves disorganising production one section of the state’s economic organisation stated that reorganisation would not happen “without a struggle of the worker’s government against the workers’ organisations.”

All these quotes are taken from the article by David Mandel in the collection of articles on workers’ control in the book ‘Ours to Master and to Own: Workers control from the Commune to the Present.’ In this he states that the contradiction between planning and workers self-management can be resolved if there are conditions allowing for significant limitations on central control and these conditions also provide workers with security and a decent standard of living. Both, he says, were absent in Russia. More important for the argument here is his view that there must be a working class capable of defending self-management.

This too did not exist in Russia and our very brief review shows this. The Bolsheviks were acutely aware of the low cultural development of Russian workers, evidenced through their lack of education, high levels of illiteracy, lack of technical skills and lack of experience in the tasks of economic administration and management. That their numbers declined dramatically, not least because of the demands of the Red Army, leaves no grounds for surprise that this experiment in workers’ control did not prove successful.

The limited character of the initial steps in control and the awareness workers had of their lack of skills were revealed in their calls for the state to reorganise production. While certain centralised controls over the economy are a necessity, and this is doubly so in order to destroy the power of the ruling classes, the socialist revolution is not about workers looking to any separate body of people to complete tasks that it must carry out.

If workers could not control production they could not be expected to control state power. This was to turn out to be the experience of the revolution and in its destruction by Stalinism the state turned into the ideal personification of socialism.

This identification of socialism with the state in the minds of millions of workers across the world continues, a product of Stalinism and of social democracy but gleefully seized on by the right. Since the state is organised on a national basis this also entailed socialism’s corruption by nationalism.

The path required to developing and deepening a genuine workers’ revolution lay not in seeking salvation in the state but in workers creation of this state themselves out of their own activity in the factory committees and soviets. The coordination, centralisation and extension of the functions of these bodies would ideally have been the means to build a new state power that could destroy and replace the old. It would also have been the organisation that would have combatted economic dislocation and provided the means for cooperative planning of production and trade with the independent peasantry.

In this sense the Russian revolution is not a model for today. While workers control came to the fore in this revolution its limitations must be recognised and a way looked to that would overcome them in future.

It might be argued that the backward cultural level of the Russian working class, while acknowledging its high class consciousness, is not a problem today. After all the working class in Ireland, Britain and further afield is literate, educated and with a large number educated to third level education. The working class is the vast majority of society, which it was not in Russia in 1917. Many workers are now highly skilled albeit specialised. This however is a one sided way of looking at things.

Firstly on the technical side the very specialisation that makes some workers skilled reflects an increased division of labour that in so far as it is deep, widespread and reflected also in a division of social roles militates against the widespread accumulation of the skills and experience of management and control.

Many workers reflect their specialisation in a narrowing of outlook but illustrates that the increased division of labour is foremost a question of political class consciousness which is at least in part a reflection of social and economic stratification of the class. Thus some workers see themselves as professionals – engineers, accountants, managers etc. and regard themselves as middle class. Just like white collar workers and state civil servants in the Russian revolution they do not identify themselves as workers with separate political interests along with other workers slightly below them in the social hierarchy. They do not identify with socialism.

Modern society in this way reflects early twentieth century Russia: the working class does not rule society, even at the behest of the capitalist class, but there are numerous social layers (the middle classes) who help the capitalist class to do so, and they imbue into themselves and others the political outlook of their masters.

Because the division of labour is increasingly an international phenomenon the road of revolution at initially the national level poses even bigger problems for workers management of production than existed in Russia in 1917. Especially in Ireland production is often a minor part of an internationally dispersed process so that control of the whole is exercised elsewhere. How then do workers take control of such production in any one country especially one lower down the value chain?

For these reasons revolution needs to be prepared. It needs prepared in the sense that workers must be won to a fully conscious commitment to their becoming the ruling class of society; a rule based on their ownership and management of the forces of production. In order to achieve this, the force of example rather than simply the power of argument is necessary. In other words workers must have seen and experienced ownership and management. This can provide many with the experience and knowledge necessary to lead the whole class to own and manage the whole economy when such control is the basis for their own state power, after capitalist state power has been destroyed.

The best, in fact only way, to prepare for socialism is through practice, practice in asserting the interests of the working class as the potential new dominant class of society. Demands for nationalisation are demands that someone else, the state – because the state is a group of people – create the good society. And when anyone is asked to create the good society it is always what is good for them.

Such dominance is more than simple resistance to the exploitation of the old society but must in some way herald the new. Opposition to austerity for example can only ameliorate the effects of capitalism and does not provide panaceas – not even ‘taxing the rich.’ The real importance of fighting austerity therefore lies in the building of the organisation and class consciousness of the working class. This is what Marx meant when he wrote in ‘The Communist Manifesto that:

“the Communists fight for the attainment of the immediate aims, for the enforcement of the momentary interests of the working class; but in the movement of the present, they also represent and take care of the future of that movement.” The future is that in its “support (for) every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things” communists “in all these movements, (they) bring to the front, as the leading question in each, the property question, no matter what its degree of development at the time.”

This then is the importance of workers’ control and workers ownership. It is the question of the future of the movement of the working class because it brings to the fore “the property question.”

I shall look at it some more in future posts.