The most damning judgements in Fragments are that the movements since 2008 ‘failed to identify an avenue through which society might be changed’; ‘it is unlikely the Trotskyist People before Profit will manage to articulate a viable alternative . . . and the steps between the current situation and the long-term goal of socialism are less clear than ever before. The radical left ‘were engaged in a form of politics incapable of realising its own aims.’ (p183, 191, 192 & 181)

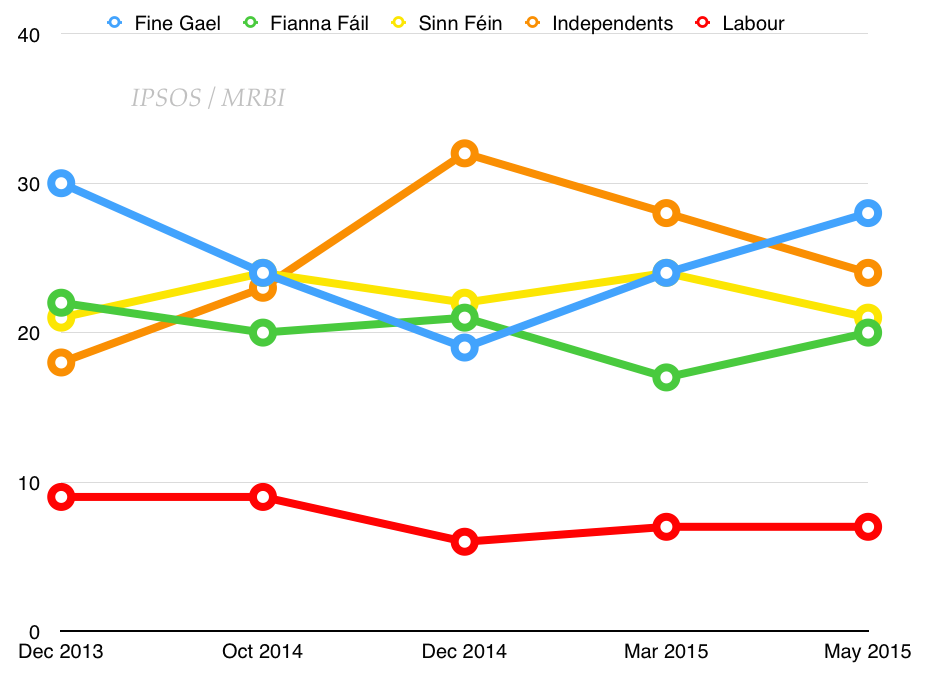

The left made gains during the years covered by the book, expressed in some relatively modest electoral successes, but this was achieved though pursuit of a strategy and practice that might be considered as one of least resistance, which had inevitable shortcomings and meant these ‘steps’ were not an ‘avenue through which society might be changed’; entailed a lack of articulation of ‘a viable alternative’; lacked clarity over how to achieve ‘the long-term goal of socialism’ and gave rise to the perception that its politics was ‘incapable of realising its own aims.’

This is not only a question of an absence of a revolutionary socialist programme, which we have already noted in previous posts. The left has worked under the assumption that achievement of its objectives requires a revolutionary party, which alone would understand the necessity for revolution and how it may be achieved, and that in its various forms it is the nucleus of this party, which is considered to be revolutionary because its leaders truly believe in revolution (regardless of how it looks from outside). This obviously means that its own activity and building its own organisations are the absolute priority.

I am reminded of the slogan that the duty of a revolutionary is to make the revolution, except socialist revolutions are not primarily made by revolutionaries but by the working class in its great majority. The emancipation of the working class can be the work only of the working class itself, as someone famous once said. This is one of many principles widely acknowledged but without understanding what it entails. Revolutionaries are ‘the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class . . . which pushes forward all others [with] the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement.’ (Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto).

The working class party is built not solely or even mainly by the activists of the left but mainly by the working class itself, with the socialist movement playing the role just mentioned. Instead, the mantra of building the party is reduced to building the existing left organisations not as a consequence of the development of mass working class movements but separate from them. Revolutionary organisations can only develop if they find within the working class this growth of socialist consciousness, which is itself partly a result of their own activity but only as an integral part of the struggles of the working class itself.

We have noted the need to challenge the existing leadership of the trade union movement as an example of what is needed to begin addressing these tasks. We have noted that the limits of single issue campaigns means that they were not a substitute, however useful they may be otherwise, and that the political education that was given was the failed statist politics that subordinates the class’s own activity to that of the capitalist state. This view has come to dominate understanding of what ‘socialism’ is and reflects the historical domination of social-democracy and Stalinism.

This was rudely demonstrated by the left’s customary call for nationalisation being appropriated by the state in relation to the banking system when it faced collapse; which was carried out to protect both capitalist ownership and itself, while dumping the cost on the working class. I have seen it defended on the grounds that this was not ‘socialist’ nationalisation, but this complaint just admits its unavoidably capitalist character. Could capitalist state ownership be anything other than capitalist? How could the capitalist state introduce working class control and ownership when it was its own ownership that was asserted?

Progress through the lines of least resistance does not necessarily involve conscious opportunism, precisely because it does involve progress, but like all opportunism it sacrifices long term principle for short term gains. Gains which can more readily dissolve as circumstances change and change they always do. The approach of appearing more ‘practical’ and attuned to workers’ existing consciousness by declaring that one can leverage the state to do what the workers movement itself must do, through a ‘left government’ for example, does not educate, in fact miseducates, the working class.

This does not invalidate the struggle for reforms that of necessity are under the purview of the state, but these are of benefit not only, or so much, for their direct effects but for their arising from the agency of the working class through the struggle to impose its will on the state and capitalist class. Reforms are ultimately required to create the best conditions for a strong workers’ movement, and not as solutions to their problems that act to co-opt workers to dependence on the state. Handed down from above they can primarily be seen as performing the latter role.

The alternative of seeking to mobilise workers when their organisations are bureaucratised and the majority are either apathetic or antipathetic, is often seen as less practical, less advised, and ‘ultra-left’. However, the point of socialist argument and agitation is often not with the expectation of eliciting immediate action but to advance political consciousness, which sometimes might be seen as widening what is called the ‘Overton window’.

This approach addresses the argument that only in revolutionary times or circumstances can one advance revolutionary demands. All independent action by the working class is a step towards its own emancipation, no matter how small, just as reliance on the state is not. Reforms won from the state are significant such steps if they involve independent organisation of the workers’ movement to achieve them. As Marx said in the Communist Manifesto in relation to workers’ struggles: ‘Now and then the workers are victorious, but only for a time. The real fruit of their battles lies not in the immediate result, but in the ever expanding union of the workers.’

Something similar was pointed out by James Connolly, who knew that temporary victories would not yield permanent peace until permanent victory was achieved, and that for such victories ‘the spirit, the character, the militant spirit, the fighting character of the organisation, was of the first importance.’ Fragments’ statements that the left ‘failed to lay deep social roots’ and ‘failed to develop a mass political consciousness’ is the authors judgement that this didn’t happen.

It is banal and trite to acknowledge that demands need to be appropriate to their circumstances, but this must also encompass two considerations. First, that even in situations in which it is almost impossible to achieve the working class mobilisation that is required, it may still also be necessary to say what must be done in order to achieve the desired outcome.

Second, only by always putting forward an independent working class position, which most often does not involve any call to more or less immediate revolutionary overthrow, is it possible for workers to begin to realise that an independent working class politics exists that has something to say about all the immediate and fundamental issues of the day. As I have previously noted, this begins by instilling in workers the conception of their own position and power as a class, not that of an amorphous ‘people’. What this involves in any particular circumstance is a political question and the subject of polemical differences that are unfortunately unavoidable.

The fall of the Celtic Tiger demonstrated that such crises on their own will not bring about the development of socialist consciousness – that capitalism is crisis-ridden and must be replaced by a society ruled by the working class. One of the earliest posts on this blog noted evidence that these crises most often do not. In order that they deliver such object lessons it is necessary for a critical mass of the working class to already be convinced that their power is the alternative to capitalism and its crises. This requires a prior significant socialist movement integral to working class life and its organisations.

We are a long way away from this, with one reviewer of the book in The Irish Times noting that its editors had excessive optimism about the experience of the Irish Left over the period. The reviewer makes other comments that are apposite. The argument of this review is that the book records enough experience to show that optimism is unjustified, at least on the basis of continuation of the political approach recorded by it.

The project of a left government that would be dominated by Sinn Fein, with secondary roles for the Labour Party, Social Democrats and Greens is not the road to address the failures noted at the top of the post. The project is a chimera that is incoherent and cannot work. In (un)certain circumstances it might spur a further development of consciousness and independent working class organisation and activity, but this is by far the less likely outcome and is not, in any case, what is being argued by the projects’ left supporters.

The left is always in a hurry, partly because of the preponderance of young people involved but more decisively because of the project itself, which is not based on building the strength and consciousness of the class as a whole but of building the left organisations themselves, particularly through elections. The next one is always the most vital. The former is the work of years and decades to which the project of ‘party building’ and ‘the immediacy of revolution’, understood as insurrection, does not lend itself. These are outcomes that cannot be willed by socialists but determined ultimately by the wider class struggle and the decisions of countless workers as well as by their enemies.

Elections allow socialists ‘a gauge for proportioning our action such as cannot be duplicated, restraining us from untimely hesitation as well as from untimely daring’, and ‘a means, such as there is no other, of getting in touch with the masses of the people that are still far removed from us, of forcing all parties to defend their views and actions.’ It is not a means to arrive at a government that is ‘left’ of the current bourgeois duopoly but right of socialism, and that peddles illusions that the current capitalist form of democracy can deliver fundamental change.

Back to part 5