“Not only do the opinion polls say that Labour will win back working class areas in Northern England it lost in 2019, but it is also expected to do well in wealthy parts of the south that were once Tory heartlands.” So read the full-page article in the Financial Times at the start of the week. The reason? “There’s only one answer to that: Brexit”, according to the Tory Chair of the House of Commons justice committee.

One section of the Tory base is leaving while the other in the so-called Northern ‘Red Wall’ is also departing, and since only one third of the electorate now still thinks Brexit was a good idea, the pool the Tories are fishing in – against the competition of the Reform party – is getting a lot smaller. Since Starmer’s Labour Party also claims that it can get Brexit to work, and is also not talking about it, it is not a surprise that the share of the vote of the two main parties is now the lowest since 1918. Only 35 % of those polled think Starmer would make the best prime minister against 19% for Sunak, the former’s rating lower than all of the recent election winners.

It is obvious that the predicted Labour landslide victory has more to do with the unpopularity of the Tories than anything to do with Starmer, so that while Labour’s support has declined during the election so has that of the Tories. The Financial Times reported that Tory support has fallen by a third since January and the view that the only issue that matters is getting rid of them has continued to dominate.

Both parties have embraced the politics of waffle with commitments that are as few and vague as the waffle is ubiquitous. “Growth” is the answer to every problem yet the Brexit elephant in the room that squats on growth is ignored. Starmer has followed Tory policy like its shadow while dropping every promise he ever made to become leader, parading his patriotism with “no time for those who flinch at displaying our flag”.

He has presented himself as a strong and tough leader –in such a way that his rating for being trustworthy has fallen from 38 to 29; his rating for honesty from 45 to 34; his rating for authenticity from 37 to 30 and, for all his posturing, his rating for charisma from 20 to 18. What we don’t have therefore is popularity born of personality to explain why it’s not born of politics or principle.

The vacuousness of the politics of the election is covered up by trivia such as Sunak taking himself off early from commemorating the D-Day landings and the betting scandal, which shows that low-level corruption is always more easily exposed than the bigger stuff. All this however is for the consumption of the masses.

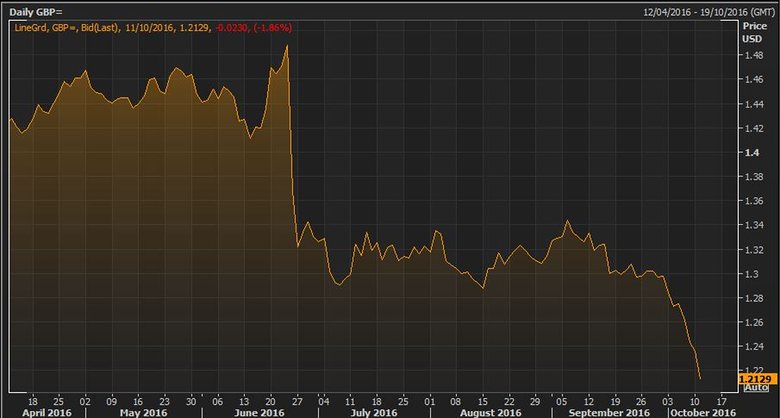

The ‘get the Tories out’ mantra that also characterises the left is perfectly acceptable to the ruling class since the Tories have failed to govern properly, leading to Brexit and Truss’s unfunded tax cuts that briefly threatened the currency and suddenly raised interest rates. Being anti-Tory is no longer a solely left-wing pursuit, which makes the primacy of getting them out (which is going to happen anyway) illustrative of the poverty and bankruptcy of many on the left.

Bourgeois commentators lament that the lack of honesty of the election ‘debate’ will lead voters to “distrust politicians and so our democracy itself” (Martin Wolf FT), while the more cynical shrug their shoulders and accept it. “The UK is approaching a general election of vast importance for its future. It just has to get next week’s one out of the way first” (Janan Ganesh FT). The first worries that the British public will not be ready for the radical attacks that are coming their way while the second is concerned only that they learn to accept them next time. Clearly both are more interested in what happens next, which doesn’t mean what happens to the Tories but what happens when we have Starmer.

One Irish commentator described him as “legendarily boring” and “resolutely moderate”, which fatuousness is what often passes for informed political commentary in the Irish press. The ruthlessness of Starmer’s dictatorship in the Labour Party and his pathological record of lying to become its leader should give even the dimmest observer pause to wonder what he will do with the exercise of real power. What struck me ages ago was the unwillingness to wonder what decisions someone so innocent of due process in the Labour Party made when he was Director of Public Prosecutions.

The Starmer government is now the threat to the working class in Britain and to us in the north of Ireland, while the Tories are receding in the rear view mirror. Preparing for this can best be done in the election by robbing this government of as much legitimacy as possible and using the election to organise potential opposition. This means not voting for the Starmer’s Labour Party but only for those on the left of the party who might be considered as some sort of opposition, including those deselected and standing as independents.

The first-past-the-post electoral system is not designed to elicit people’s true preferences but incentivises many to vote against parties and not who they are for. When there is widespread disenchantment with the major parties this can be muffled and stifled. Yet even with the current system we have seen support for the two main parties fall and ‘wasted’ votes for others may encourage further politicisation.

The Financial Times report that behind the steady gap between the Tories and Labour that will give Labour a ‘supermajority’ is a drop in Labour’s polling matching a fall in that of the Tories. These trends may reverse as voting approaches but at the moment they show that their ‘competition’ is not strengthening either. The FT claims that the Labour Party is experiencing high levels of turnover in its support, losing a quarter of those who had previously (January this year) said they were planning to vote for it. Three per cent were undecided, 9 per cent were less likely to vote, and 4 per cent were going to vote for the Lib Dems while potential Lib Dem voters were travelling in the opposite direction, perhaps for tactical reasons.

The proportion of voters who switched parties in elections used to be about 13 per cent in 1960 but is nearer 60 per cent now. Some might lament that this illustrates a decline in class consciousness but since this was often an habitual Labourism it is not the loss that it may appear. What has suffered a greater loss is the coherence of the left that now mainly rallies behind its own ruling class, today in a war that has the potential to escalate catastrophically and which involves endorsement of all the hypocritical claims of the British state and ruling class it claims it oppose. The consensus on the war is something that the war itself may have to break.

Those of us on this side of the Irish Sea have looked on with a wry smile at the sudden discovery by many in Britain that the Democratic Unionist Party is ant-women and anti-gay.

Those of us on this side of the Irish Sea have looked on with a wry smile at the sudden discovery by many in Britain that the Democratic Unionist Party is ant-women and anti-gay.

Some people might object to the view expressed in the previous

Some people might object to the view expressed in the previous  One of the very few things that has made me smile in the whole Brexit debacle has been the leader writers and columnists of the financial press, including the ‘Financial Times’ and ‘The Economist’. Brexit is almost universally regarded by these people as a disaster and some have blamed David Cameron for being a reckless gambler and bringing them to their current predicament.

One of the very few things that has made me smile in the whole Brexit debacle has been the leader writers and columnists of the financial press, including the ‘Financial Times’ and ‘The Economist’. Brexit is almost universally regarded by these people as a disaster and some have blamed David Cameron for being a reckless gambler and bringing them to their current predicament.