The second set of changes to the Constitution proposes deleting the current Articles 41.2.1 and 41.2.2 and inserting a new Article 42B.

Article 41.2.1 states “In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.”

Article 41.2.2 states that “The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.”

These are to be replaced by inserting a new Article 42B:

“The State recognises that the provision of care, by members of a family to one another by reason of the bonds that exist among them, gives to Society a support without which the common good cannot be achieved, and shall strive to support such provision.”

The two existing Articles are said to be sexist and based on Catholic teaching, such as the encyclical from 1891 in which Pope Leo XIII stated that ‘a woman is by nature fitted for homework . . .”, while it is believed that the Article was written by the Catholic archbishop, John McQuaid.

A socialist might note that it is not the role of working class women, or men, to support the State and that the State is not about “the common good” but about what is good for bourgeois private property, something the Irish State’s constitution is well known to be very good at protecting.

The commitment to “ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home” not only assumes that it is women who must carry out domestic labour but also pretends that the state will help them avoid the economic necessity to go out to work. The necessity to go out to work is a requirement of capitalism, otherwise there would be no working class to exploit, and it would not make much sense to effect equality by limiting this to only one sex, if it were possible, which it is not.

The Article had not much success in keeping many women “in the home” because economic necessity compelled them to seek paid employment. In fact, it did not have much success in keeping them in the country, as hundreds of thousands emigrated in search of a better life. This led to agonised concern that there were “moral dangers for young girls in Great Britain”, including that they might get pregnant.

As the Irish economy expanded in later decades more and more women entered the labour force although there is now concern that their presence is still relatively low. Women’s participation in the labour force grew only slowly, from 28 per cent in the early 1970s to 32 per cent in 1990, rising rapidly during the economic boom to over 63 per cent in 2007. In the third quarter of 2023 the participation rate for females was 60.8% compared to 71.1% for males. Nothing of this had anything to do with the words in the constitution and everything to do with the workings of the capitalist economy.

Socialists should welcome the higher participation of women in the workforce both for the position of women in society and for the potential unity of women and men in the struggle to emancipate themselves from the domination of capitalist accumulation. Domestic labour should be shared equally, and as far as possible should be socialised so that individuals of both sexes are able to exercise greater choice over whether, and how much, to work. This, however, recognises that those able to work should work and under capitalism have mostly no choice.

There are some things that cannot be shared equally, but the concern to be ‘progressive’ in the sense of what has been called ‘virtue signalling’ and ‘performative activism’ means that this has been deliberately ignored. The wording of the replacement Article is instructive not only because of what it says but because of what it doesn’t say.

If almost everyone is a member of a family and part of some sort of ‘durable relationship’ then the support given to Society by the care shown to each other by members of a family is simply the support given to all members of a family by Society. It’s a truism that it is people in society who care and support each other. The question is, what is the Irish State, through its Constitution, going to do to help? How will it address the large additional labour carried out by women in paid employment through domestic labour?

The answer, if we look at the Article, is nothing much. It “shall strive to support such provision” of care but commits to nothing, which means its ‘striving’ is meaningless, but rather points to the concept of caring being an individual concern of “members of a family” but of no fundamental responsibility of the state.

The state, however, is supposed to represent the general interest, “the common good”, as it is called here. I suppose socialists should welcome the clear message for anyone that cares to discern it, that the provision of care is a private matter, or perhaps a privatised matter that the state will rely on becoming a wholly commodified service to be produced like all commodities in capitalism–for a profit.

It has been pointed out, and is also referenced above, that the Article drops any refence to women, while the two existing Articles reference them, albeit in reactionary terms. The current Governing parties are not keen on talking about women and their rights because they have decided that women are some sort of thing that men can become if they put their mind to it. I will be posting soon on Gender Identity Ideology but suffice to say here that the Irish State recognises that men can legally change sex by declaration.

The state cannot therefore recognise the role of women in society, and their specific contribution has to be ignored and covered under the general rubric of “care”. Except “care” doesn’t cover it; it doesn’t cover what many women do, and only women can do. Within whatever definition of family that the Governing parties want accepted, if it includes women, the contribution they make not only may include a major share of the care of others, but also the carrying of new humans to birth through pregnancy and breastfeeding thereafter.

This, however, would be to recognise the essentially biological nature of women and the Governing parties have decided to reject this. They are therefore unable to recognise the real role of women in society and so substitute a new form of sexism for the old.

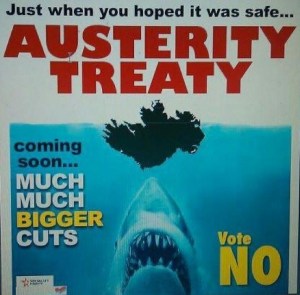

Given all these considerations in this and the previous post it is clear that the changes to the constitution should be rejected. The false promises of extra funding to social services as a result of a yes vote from some, and the ‘unenthusiastic’ support of People before Profit because of its vacuousness are pointers. This, and the previous, post have argued that these are the least of the reasons to vote No.

Back to part 1