Alexis Tsipras justified his humiliating U-turn, and commitment to imposition of austerity worse than he had just rejected, by saying that he had no mandate for Greece to exit the Euro. Very true. But he had just claimed that the referendum a week before had not been about the Euro. By 61 to 39 per cent he has no mandate for austerity, which is what he said the referendum was really about.

Alexis Tsipras justified his humiliating U-turn, and commitment to imposition of austerity worse than he had just rejected, by saying that he had no mandate for Greece to exit the Euro. Very true. But he had just claimed that the referendum a week before had not been about the Euro. By 61 to 39 per cent he has no mandate for austerity, which is what he said the referendum was really about.

He came into office promising an end to failed bail outs and has ended with a third one bigger than the first. He called for debt reduction and now seeks support for debt inflation.

Such is the scale of the crushing terms of the latest ‘bailout’ that no one is attempting to say that it is nothing other than complete humiliation for Greece. Even the Eurozone bureaucrats stated the truth behind the unpalatable words spewed out by their leaders – Tsipras had been subjected to “mental waterboarding” and had been “crucified”.

What has been mental torture for Tsipras will be brutal and catastrophic austerity for the Greek people.

I could write a whole blog on the capitulation of Tsipras and what looks like the majority of Syriza, and there would be good political reasons for doing so. The policy and strategy of Syriza has been endorsed by Irish opponents of austerity such as Sinn Fein and these now lie in tatters.

In fact in my own view Sinn Fein is not even as radical as Syriza and this is an easy claim to substantiate. It has already implemented austerity in the North of Ireland while hiding behind opposition to some welfare cuts. In the South it supported the fateful decision to make the debts of corrupt banks and property speculators the burden of Irish workers and in doing so made the struggle against paying this odious debt much more difficult.

But there will be plenty of voices pointing out that what radical politics Sinn Fein has to offer have been trialled in a real life laboratory and been found wanting. The capitulation of Syriza is in principle no greater than the Republican’s own acceptance of British rule in Ireland, acceptance of partition, surrender of weapons and dissolution of the IRA. But that is all now a history that no one wants to talk about.

What is more important therefore is to try to understand what has happened and whether it could have been any different. Not that it must be accepted that the ‘coup’ against Greece cannot or will not be resisted. It can and will but it would be blindness to reality not to acknowledge that under Syriza the fight against austerity has suffered a demoralising defeat.

As that new aphorism says: it’s not the despair, I can take the despair. It’s the hope. Syriza gave hope.

Working out what has happened is not easy. For the man or woman on the street they see television reports of quantitative easing by the Eurozone involving the figurative printing of millions of Euros by the European Central Bank, yet this same institution is involved in the vindictive pursuit of Greece for sums it could easily accommodate.

The proposals of the conservative leaders of the EU seem equally hard to understand or justify. In fact for many they seem stupid, if not crazy. So draconian are they that they seem designed to achieve the very opposite of what they claim to be for.

The imposition of yet greater austerity when this austerity has demonstrably failed might be explained by ideological blindness. And the humiliation involved might seem to invite rejection while being another attempt to remove Syriza from office. But many commentators have explained that Syriza may possibly remain the only force that can push austerity through without complete chaos and collapse.

This humiliation is perhaps not just a message to a small and weak Greece but an unmistakeable one to a larger Italy and France: that the development of the EU will be under a model defined by Germany and its allies. Yet even here the degree of malevolence can only invite small countries with parties equally blinded by reactionary ideology as Germany to wonder just what fate would befall them in an EU with such a definition of ‘solidarity.’

So while ‘good’ reasons might be found for what would appear to be ideological blindness the proposal for a “timeout” exit by Greece from the Euro appears as simply stupid; unless of course it is also a means of pushing Greece out permanently. But then it is such a stupid idea as justification that its purpose might only seem to be how open the imperial bullying can become, ‘pour encourager les autres’.

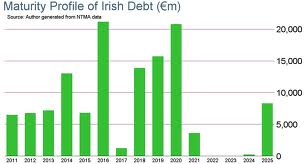

For the Greek people the surrender of even nominal control of their affairs is way beyond what has gone before. The original proposal to ring fence €50 billion of Greek assets under German control, to be sold at the discretion of its creditors, was such an open declaration of debt bondage as to render the humiliation utter and complete. What is yours is no longer even yours to sell. Now it is reported it will simply be wasted on insolvent Greek banks with the needs of financial capital once again talking precedence not only over people but over real productive activities.

Thus in many ways, its failure to actually work being the first, its effects on undermining the legitimacy of the EU second and materially weakening the incentives to solidarity among its members third, all make the bailout deal a defeat for the idea of a European Union. This is not even a European imperialism to rival the US, Russia or China but an imperial core and vassal periphery.

The price being paid seems so unnecessary because the main demand of Syriza – in order to give hope and reduce the impact of austerity, i.e. debt forgiveness, will be given and is already hinted. Not in the shape of outright reduction but in the form of postponing or extending repayments and similar measures on the interest due. After all, what cannot be repaid will not be repaid.

What matters however to the right wing conservative leadership of Germany, the Netherlands etc. is that their strength, and by extension that of the European imperialist project, is not diluted by the weak European nations and that the Euro remain in position as a world currency and not a vehicle for default and certainly not by what is considered an advanced nation. Greece must be bled dry in order that the Euro remains strong and the pretensions of the EU remain in place.

The vision of a united Europe is not being abandoned by Germany etc, but it is one in which austerity is the bond that unites. It can be claimed that austerity will be inflicted on German workers if crisis hits the German banks; except of course that Germany has broken the rules before and would do so again. It is easier to be ideologically blind when the price is paid by someone else.

Could it have worked out differently? Syriza had hoped that enlightened self-interest would have combined with pressure from the US and the legitimacy gained by the referendum to mitigate the demands for austerity by Germany, The Netherlands and all the other little right-wing led states that curry favour with the powerful. They have been rudely disabused of their illusions.

The more fundamental reason for this outcome is the weakness of the alternative at an international level. Where were the left wing Governments calling for debt forgiveness, an alternative to austerity or even its reduction? Where were the mass movements pressurising their Governments to accede to Greek requests? Greece could not push back the demands of much stronger states on its own but on its own it was.

The demand for a revolutionary socialist alternative seeking the destruction of the Greek capitalist state and take-over of the Greek economy by its workers fails to provide any sort of immediate alternative, which is what we are discussing, for two rather obvious reasons.

Such a strategy relies on the aspiration and activity of the working class and the Greek working class neither desires nor is organised to destroy the existing state, create its own and take over the running of Greek production. The anti-capitalist ANTARSYA for example got less than 1 per cent of the vote and Syriza, it should not need to be said, is not a revolutionary party. How does a revolution arise out of this except through a long and painful process of learning lessons and making advances on this basis?

I was recently reading an article entitled ‘Marxism and Actually Existing Socialism’ written, what seems like a long time ago, before the collapse of the Soviet Union, and which defended Marx’s theory and politics. In it the author wrote that:

“Marx envisaged that socialism would come first in the most advanced industrial societies of Europe, and it has not done so. Arguably, however, Marxism is capable of comprehending this fact. In any case, this is a matter of detail, even if an important one; and it seems difficult to resist the conclusion that, in its broad and general outlines, Marx’s account of the historical tendencies of capitalism has been remarkably confirmed by historical events.”

But of course the coming of socialist revolution not to the most advanced countries is not a detail, not even an important one. It has been fundamental to the development and future possibility of socialism and has led to the very definition of socialism being distorted and disfigured.

Socialism is not possible in Greece alone any more, and certainly less, than it was in Russia not least because it is too weak and poor. It is obvious that no other working class within any other country in Europe is at a stage of development where it could either join or support working class rule in Greece.

This does not mean Syriza should not have taken office or that it should not have engaged in negotiations with the Troika. Its strength however derives fundamentally from the class consciousness and organisation of the working class and not from any superior moral position. The building of an international European party of the working class, of a militant current within the working class movement including trade unions, and of international workers’ cooperatives is the only road to creating the foundations for a successful conquest of political power.

On the other hand capitalist economic and political crises and socialist propaganda are, respectively, simply the occasion for such a conquest and the means of spreading word of the need for it.

As I have said before: the worst result would be Syriza implementing austerity. It should now reject the bailout, call fresh elections on such a platform and if elected pursue an alternative. If in opposition it should develop a movement as set out above.

The alternative it should pursue is that which the Irish should have carried out in 2008. Let the banks go bust and let its owners and lenders take part in a ‘bail-in’ in which they pay the price for their investment in insolvent companies. This is sometimes known as capitalism.

A radical Greek Government would encourage Greek workers to turn the banks into cooperatives that would shed their bad debts into a ‘bad bank’ (like NAMA in Ireland, in theory if not in its practice) and guarantee deposits that would fund development of worker owned enterprise.

The Greek debt would thereby suffer default and the reactionary gamblers Merkel, Juncker, Schäuble, Draghi and Dijsselbloem would see where the chips fall.

The blogger Boffy has suggested that a solution to the currency problem would involve electronic Euros that would allow circulation of money without the requirements for additional notes etc. from Brussels. While this could work for the domestic economy I cannot see how it could function as a means of payment for international trade and, while Greece is a relatively closed economy, it cannot function without it.

In any case the leadership of the EU would, on current form, expel Greece from the Euro and introduce its own capital controls on the country.

Greece would be forced into issuing a new currency, a new Drachma, which the people do not want. This could not be done quickly or without significant disruption. It has been asserted that the argument that this would result in devaluation and a massive reduction in Greek living standards is false because the catastrophe predicted has already happened. ‘Internal devaluation’ has already achieved what external devaluation of the new currency would otherwise have done.

I am not convinced by this argument but this too might be academic if the EU decided that Greece would no longer be part of the Euro.

The strategy suggested therefore provides no guarantee of success. There is no ‘technical’ solution or answer in this sense. And why should one be expected?

I have said that socialist revolution depends on the prior creation of a working class power consisting of an international party, international trade union action and development of workers’ cooperatives on an extensive scale. What on earth could substitute itself for these?

What is suggested is a strategy for struggle and not a ‘solution’ but we have reached the stage where not even the leaders of the EU can present false promises on this with any credibility. Austerity will continue not to work. Struggle is what we have.