When five political commentators were asked for the main moment of the election campaign, they all mentioned the TikTok Taoiseach’s snubbing of a disability care worker when he was on one of his many walkabouts. It “cut through” to the public, as the saying goes, and probably did lower the Fine Gael vote a little. However, in the grand scheme of things all it demonstrated was the irrelevance of the campaign, which has been described as a non-event. Unlike recent general elections in many other countries, the incumbents were returned to office, providing evidence of political stability that does not exist elsewhere. This stability rests on uncertain foundations.

The election was called following a large give-away budget of tax reductions and increased state spending, followed by a campaign where everyone promised even more tax cuts and increased spending. This included the previous austerity-merchants in Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. Halfway during the campaign, when Sinn Fein joined the club, Fine Gael launched hypocritical denunciations that it was about to break the “state piggy bank”.

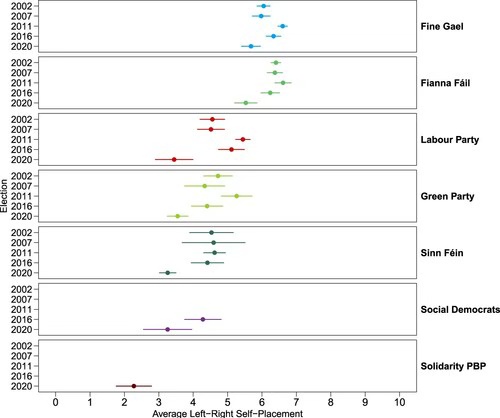

On the surface, the only difference between the governing parties and the different varieties of opposition was how much they would spend. People before Profit claimed that their clothes were being stolen by everyone, at least for the election, while media commentators claimed that the widespread consensus on increased state intervention showed what an essentially leftwing country Ireland was. Since PbP argues that such intervention is an expression of socialist politics these claims would be right – if PbP was also right, which it’s not. The view of politics as a spectrum from left to right implies no fundamental difference between the government and opposition but only shades or degrees of difference.

If this didn’t provide the grounds for major change, and the existing alignment of party support made it unlikely, the most important reasons for continuity are the foundations of the state itself and the economic success that has satisfied a significant part of the population, if only on the grounds that it could be a lot worse and recently was. The ‘left’ appeared as wanting to share the gains more equally. Unfortunately, those seeking equality inside the Irish state have to reckon on the giant inequality outside on which it would have to be based and which determines it.

The largesse of recent budgets, and the promises of more during the election, rest on the existence of the Irish state as a tax haven where many US multinationals have decided to park their revenue for tax purposes alongside some of their real activities. Over half of the burgeoning corporate tax receipts come from just ten companies, with the income taxes of their employees also significant. Trump has threatened tariffs on the EU, which threatens the massive export by US pharmaceutical firms to the US, and has promised to reduce corporate taxes, which also reduces the attractiveness of the Irish state to multinational investment. It is not so long since the shock of the Celtic Tiger crash, so very few will not be aware of the vulnerability of economic success and the finances of the state.

This vulnerability was ignored in recent budgets and election promises while the electorate is blamed for seeking short term gains that are all the political class can truthfully promise. Failure to invest in infrastructure has weakened the state’s long term growth with the major shortfalls ranging wide, across housing, health, transport, childcare and other infrastructure such as energy and water. This has led to calls for increased state expenditure as the existing policy of throwing money to incentivise private capital has fallen short even while the money thrown at it has mushroomed. Bike sheds in Leinster House costing €336,000, and a new children’s hospital that had an estimated cost of €650m in 2015, but costed at €2.2 billion at the start of the year – apparently the most expensive in the world – are both examples of the results of a mixture of a booming capitalist economy and state incompetence.

The consequences are an electorate that wants change but doesn’t want or can’t conceive of anything fundamental changing. Government and opposition differ on degree but avoid the thought of challenging the constraints their lack of an alternative binds them to. Trump is only one of them; Irish subservience to the US has already destroyed all the blarney about Irish support for the Palestinian people. Gestures like recognition of a corrupt Palestinian state are nauseating hypocrisy beside the secret calls to the Zionist state promising lack of real action; selling Israeli war bonds to finance genocide by the Irish central bank, and the three wise monkeys of the three government parties ignoring the use of Irish airspace to facilitate the supply of weapons employed in the genocide.

The Irish state is not in control of its destiny and its population is aware of its vulnerability. For a left that bases itself on the capacity of the state this is a problem; involving not just the incompetence, the bottleneck constraints on real resources, and the international subservience to Western imperialism. The fundamental problem is in seeing the state as the answer. Were the Irish state stronger, it would have joined NATO and more directly involved itself in the war in Ukraine; it would have intensified its support to US multinationals, and perhaps been a bit better at building bike sheds and a children’s hospital.

Parts of the left seems to think the current Irish state can oppose NATO, oppose war and perhaps tax US multinationals a bit more. It is, however, currently on the road to effective NATO membership; is more or less unopposed in its support for Ukraine in its proxy war; and already taxes multinationals on a vastly greater scale than almost any other country I can think of.

The left doesn’t have an alternative ‘model’ because its alternative isn’t socialist, but simply development of the state’s existing role, presided over by some sort of inchoate left government, the major distinguishing characteristic of which is that it doesn’t include Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. This is so anaemic a strategy it avoids all the above reasons why it has minority support.

The terms in which this is popularly understood do not go in the direction of a socialist programme because of the generally low level of class consciousness, but a genuinely socialist path requires rejection of the current statist approach of ‘the left’. That this too is currently very far away reflects not only the very low level of class consciousness but also how the forces that are responsible for this have also debased the left itself, especially the part that thinks itself really socialist. Instead, we have the stupidities arising from the commonality of increased state intervention among all the parties repeatedly declared to be proof that Ireland is a left wing country.

These constraints explain the difficulty in creation of a left alternative to a Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael government; the fragmentation of the left and its Oliver Twist policies of simply asking for more. There are numerous permutations possible before any purported left government would arise, with Sinn Fein, Independents, Social Democrats, Labour Party, and others all willing to go into office with either (or both) of them. About the least likely is a ‘left’ government (in any meaningful sense) that excludes them and is composed of Sinn Fein – the austerity party in the North – and the Labour Party and Social Democrats whose whole rationale (as the good bourgeois parties that they are) is to get into office – they don’t see the purpose of being involved in politics if you don’t.

All the calls for a ‘left’ government free of the two uglies is based on the same bourgeois conceptions. Even if only on the grounds of the Chinese proverb – to be careful what you wish for, the failure in the election to achieve such a government is not grounds for mourning, even if the result invites it.

Back to part 1

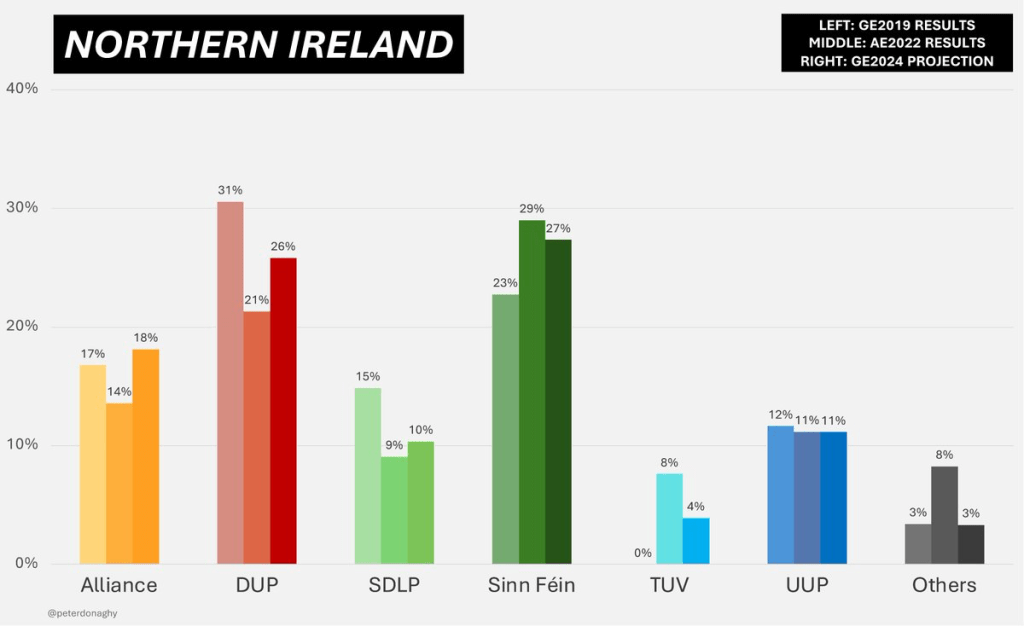

Lots of superlatives have been employed to describe the results of the Irish general election, almost all reflecting the dramatic growth of the vote for Sinn Fein, which is now the largest party in terms of popular support with 24.5%. In 2016 it had only 14 % of the vote.

Lots of superlatives have been employed to describe the results of the Irish general election, almost all reflecting the dramatic growth of the vote for Sinn Fein, which is now the largest party in terms of popular support with 24.5%. In 2016 it had only 14 % of the vote. This week’s Irish Times/Ipsos MRBI opinion poll reported that Sinn Fein is potentially headed to be the biggest party in this weekend’s general election, While it’s on 25% support, the governing party Fine Gale is on 20% and the opposition Fianna Fail on 23%. Sinn Fein has almost reached these levels of support before in the Irish State but never in first place.

This week’s Irish Times/Ipsos MRBI opinion poll reported that Sinn Fein is potentially headed to be the biggest party in this weekend’s general election, While it’s on 25% support, the governing party Fine Gale is on 20% and the opposition Fianna Fail on 23%. Sinn Fein has almost reached these levels of support before in the Irish State but never in first place.