A recently published book has examined the influence of republicanism on Marx’s politics and explained that it was the main rival to socialism for the allegiance of the developing working class for much of the 19the century. (Citizen Marx: Republicanism and the formation of Karl Marx’s Social and Political Thought, Bruno Leipold) It explains that socialism at this time was largely anti-political, in that it thought political struggle was irrelevant to the emancipation of the working class, and that it was Marx (and Engels) combination of socialism with political conceptions from republican political thought that propelled them to elaborate their politics, including the fight for the political rule of the working class (see Marx’s own statement of what he considered his own contribution to be).

In doing so they superseded both non/anti-political socialism and radical democracy that did not seek the overthrow of bourgeois private property. Marx condemned those republicans who see “the root of every evil in the fact that their opponent and not themselves is at the helm of the state. Even radical and revolutionary politicians seek the root of evils not in the nature of the state, but in the particular state form, which they wish to replace with a different state form.” As Leipold notes, Marx thought that ‘Workers thus needed to move on from seeing themselves as “soldiers of the republic” and become “soldiers of socialism.” (The King of Prussia and Social Reform, Marx quoted in Citizen Marx p161 and 163).

It would therefore be a mistake, in acknowledging the contribution of republican thought to Marx, to give it a centrality to his politics that it doesn’t have, which danger depends of course on what might be claimed for it.

It should be noted that Marx was to develop his ideas on the political power of the working class and the state considerably from 1844 and also that the vast majority of what is called socialism today, including the claims of many ‘Marxists’, wholly propagate what Marx criticises here, often professing to agree with him while doing so.

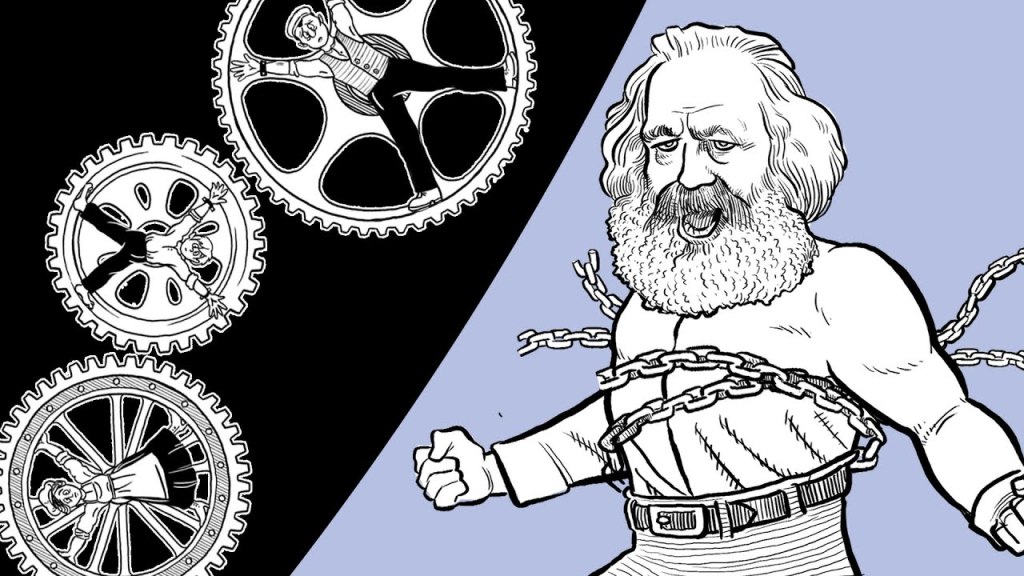

Leipold argues that Marx moved beyond republicanism after coming to an awareness of the shortcomings of existing republican revolutions in America and France; from meeting prominent socialists and social critics in Paris, including reading the writings of his future friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels; and meeting French and German workers in their various underground communist worker organisations. One result was Marx’s identification of the role of labour in human flourishing, rather than overturning the exclusion of workers from full political participation, which was the centre of republican politics (see the previous posts on alienation). The emancipation of the working class was not only its alone since “in their emancipation is contained universal emancipation”. (Marx, quoted Citizen Marx p175).

This did not mean the exclusion of the fight for political rights, which Marx and Engels both thought was vital to and for the political development of the working class, but that democracy ‘had become completely inextricable from social issues so that “purely political democracy” was now impossible and in fact “Democracy nowadays is communism”’ as Engels put it in 1845. (Citizen Marx p 172).

This new political commitment led to disputes with republican revolutionary thinkers even before Marx and Engels’ writings on the nature of their communism had been fully published and made known. Many of the criticisms made by their opponents are still common so the responses to them are still important to a presentation of their politics today.

Their political opponents at this time also consisted of a diverse group that they termed “true socialists”, who substituted moral claims for class struggle, and eschewed the fight for political rights that Marx considered “the terrain for the fight for revolutionary emancipation” even if it was “by no means emancipation itself.” (Citizen Marx p190). These rights included trial by jury, equality before the law, the abolition of the corvée system, freedom of the press, freedom of association and true representation.” (Citizen Marx p213).

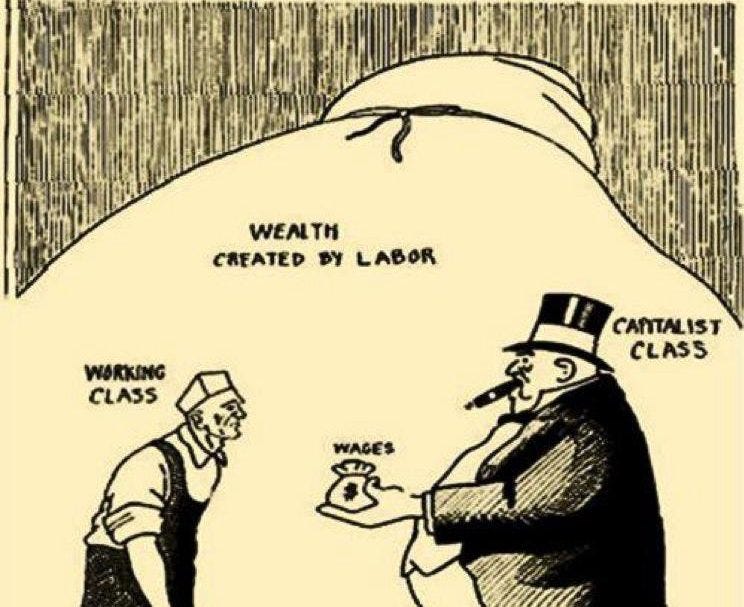

Through this approach Marx and Engels were able to rebut the criticism of radical republicans that they were effectively on the side of reaction in the political struggle against autocracy. In turn they denounced republican revolutionaries as petty bourgeois who demanded a ‘social republic’ or ‘democratic republic’ that did not “supersede [the] extremes. Capital and wage-labour” but “weaken their antagonism and transform them into harmony”. (Marx 1851-52, quoted in Citizen Marx p222).

Republican politics was petty bourgeois because it did not reflect the potential collective working class ownership of the forces of production, which required such ownership because of their increased scale and division of labour, but instead sought the widening of individual property ownership. This reflected the still large number of artisan workers whose individual ownership and employment of their own labour was being undermined by expanding workshop and factory production. For Marx, to seek to go back to craft production was a harkening to a past that could not be resurrected and was thus reactionary.

The grounds for Marx and Engels criticism of revolutionary republicans and non/anti-political socialists was their materialist analysis of existing conditions (which various forces were opposed to) and which included identification of the social force – the working class – that was to overthrow these conditions and inaugurate the new society. In the previous posts of this series, we have set out how these conditions were to be understood – centring on the developing socialisation of the productive forces – and the necessary role of the working class. These grounds required the prior development of capitalism and the irreplaceable role of the working class in the further development of the socialisation of production.

The alternative to capitalism developed by Marx was therefore an alternative to capitalism, not to some prior feudal or semi-feudal society; not dependent on some overarching moral ideal or future model of society, and not on the basis of the degree of oppression suffered by different classes or parts of the population under existing conditions.

In the first case there would be no, or only a very small, proletariat as a result of underdeveloped forces of production, which would limit their existing socialisation and therefore preclude collective and cooperative production. In the second, Marx and Engels were averse to ideal models arising from individual speculation about the future form of society, and were aware that the application of moral criteria to the construction of a new society was subject to the constraints of the existing development of the forces of production and attendant social relations. In the final case, there were more oppressed classes than the working class, the peasantry for example, which until recently was also much more numerous, and more oppressed layers of society, including women, and working class women in particular.

Their ideas and politics were therefore not crafted to be superficially appealing but to be appealing because they corresponded to reality, one that was to be humanised by a class that itself had to undergo as much change as the society it was called upon to transform. As Marx and Engels noted in The German Ideology:

‘Both for the production on a mass scale of this communist consciousness, and for the success of the cause itself, the alteration of men on a mass scale is necessary, an alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; this revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew.’

In his book ‘Citizen Marx’ Leipold notes that the implications of this were “a hard pill for workers to swallow.” (p243):

‘But we say to the workers and the petty bourgeois: it is better to suffer in modern bourgeois society, which by its industry creates the material means for the foundation of a new society that will liberate you all, than to revert to a bygone form of society, which, on the pretext of saving your classes, thrusts the entire nation back into medieval barbarism.’

Part 62 of Karl Marx’s alternative to capitalism.

Back to part 61

Forward to part 63

Part 1 here