In a Facebook discussion on why socialists should oppose the war I received a reply that stated:

‘In ninety cases out of a hundred the workers actually place a minus sign where the bourgeoisie places a plus sign. In ten cases however they are forced to fix the same sign as the bourgeoisie but with their own seal, in which is expressed their mistrust of the bourgeoisie. The policy of the proletariat is not at all automatically derived from the policy of the bourgeoisie, bearing only the opposite sign – this would make every sectarian a master strategist; no, the revolutionary party must each time orient itself independently in the internal as well as the external situation, arriving at those decisions which correspond best to the interests of the proletariat. This rule applies just as much to the war period as to the period of peace.’

This of course is a quote from Trotsky. The problem is not to quote this as if this explains left support for the Ukrainian/Western imperialist alliance, but why this combination requires socialists to place a plus sign when the chances are only one in ten of that being correct.

If we look at the examples in the article from which the quote is taken, we see the sort of circumstances in which this would be correct. These include when a ‘rebellion breaks out tomorrow in the French colony of Algeria’ and receives help from a rival imperialism such as Italy. The second is when ‘the Belgian proletariat conquers power . . . Hitler will try to crush the proletarian Belgium’ and’ the French bourgeois government might find itself compelled to help the Belgian workers’ government with arms.’

In a footnote, Trotsky says that: ‘We can leave aside then the question of the class character of the USSR. We are interested in the question of policy in relation to a workers’ state in general or to a colonial country fighting for its independence.’

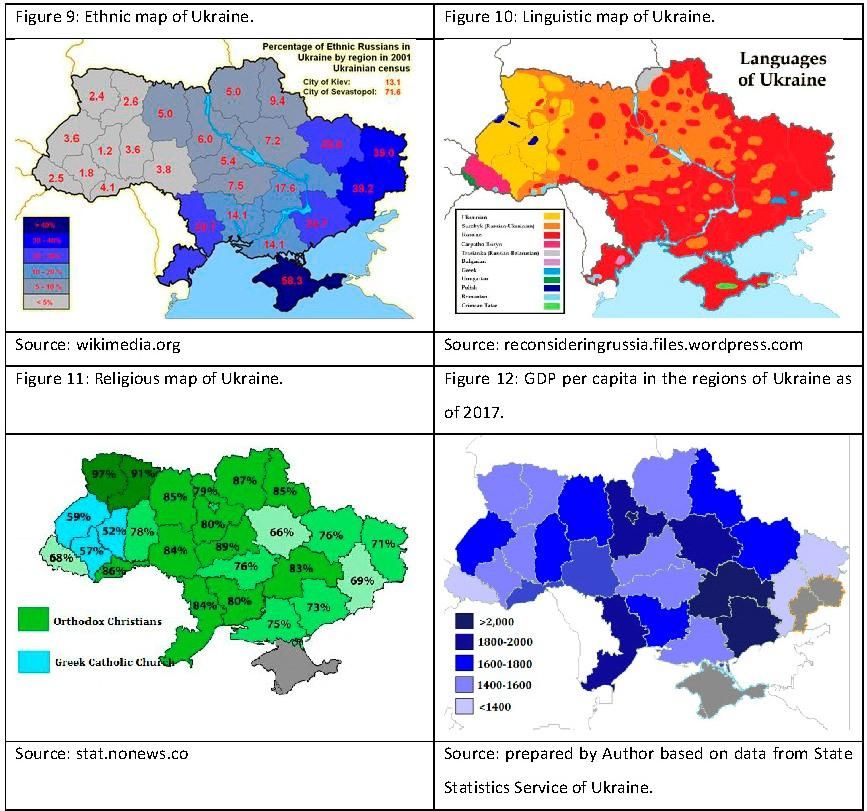

The Ukrainian working class has not come to power; Ukraine is not a workers’ state and has just celebrated Independence Day, so it is not a colony. Some have tried to squeeze in the ridiculous idea that it is an oppressed country, but this is false. It is a country backed by the whole of Western imperialism; is in an open alliance with it, and the war was provoked by both parties to this de facto alliance which sought to make it formal.

Ukraine will most likely lose territory but will not be totally occupied, unless Russia does something stupid, which it has not signalled it will do. At least part of the territory occupied is pro-Russian so that it is not possible to see either sides’ occupation as being unambiguously liberating. In other words, thinking in terms of oppressor and oppressed states does not provide a solution; more fundamentally because this is an imperialist war in which Ukraine is on one of the sides, and cloaking it with oppression does not explain either the origin and nature of the war or the approach that socialists should take to it.

Victory for Ukraine, it is claimed, would be a victory against Russian imperialism, but it would also be a victory for Western imperialism with which Ukraine is now an ally. Claims that this is any sort of anti-imperialist war are therefore obviously spurious. Only from a campist position can it be claimed that a victory for the camp of western imperialism is preferable to a victory of the Russian. Complete disorientation and political degeneration explains why supporters of this position regularly accuse those opposed to it of ‘campism’ and describe themselves as ‘internationalist.’

It is irrelevant who fired the first shot, as Trotsky noted elsewhere:

‘Imperialism camouflages its own peculiar aims – seizure of colonies, markets, sources of raw material, spheres of influence – with such ideas as “safeguarding peace against the aggressors,” “defence of the fatherland,” “defence of democracy,” etc. These ideas are false through and through. It is the duty of every socialist not to support them but, on the contrary, to unmask them before the people.’

“The question of which group delivered the first military blow or first declare war,” wrote Lenin in March 1915, “has no importance whatever in determining the tactics of socialists. Phrases about the defence of the fatherland, repelling invasion by the enemy, conducting a defensive war, etc., are on both sides a complete deception of the people.”

He goes on: ‘The objective historical meaning of the war is of decisive importance for the proletariat: What class is conducting it? and for the sake of what? This is decisive, and not the subterfuges of diplomacy by means of which the enemy can always be successfully portrayed to the people as an aggressor. Just as false are the references by imperialists to the slogans of democracy and culture.’

Trotsky makes the following summary judgement: ‘If a quarter of a century ago Lenin branded as social chauvinism and as social treachery the desertion of socialists to the side of their nationalist imperialism under the pretext of defending culture and democracy, then from the standpoint of Lenin’s principles the very same policy today is all the more criminal.’ Over one hundred years has passed since Lenin’s judgement, how much more does this criminal treachery deserve condemnation today?

The depths of disorientation can be gleaned from one article reviewing the latest film documentary on the war, in which the author states that the film 2000 Meters to Andriivka is ‘the Ukrainian working class at war.’

‘The young men we see in this documentary about the capture of a village called Andriivka by the 3rd Assault Brigade of the Ukrainian army are a snapshot of the country’s working class. One is a lorry driver, their commander previously worked in a warehouse and a third is a polytechnic student studying electronics. They are virtually all in their early twenties and all volunteered to fight the Russian invasion.’

‘Ukraine continues to resist against overwhelming odds at the price of losing its bravest and most self-sacrificing young people’, while telling us why they are fighting, reminding him of the Soviet ‘partisans fighting Nazi invaders.’ What a pity for such a claim that it is the 3rd Assault Brigade of the Ukrainian army that the author lauds, which is composed of today’s Nazis, and hails as its historic heroes the Ukrainian fascists who collaborated with the Nazis in World War II and who fought Soviet partizans.

Aleksei ‘Kolovrat’ Kozhemyakin looks at a photo of himself. Exhibition opening in Kyiv, September 27, 2023. Source: Vechirnii Kyiv

The author, like me, will have been stopped in the streets of Belfast many times by soldiers of the British army who may have previously been lorry drivers or worked in a warehouse; certainly more or less all of them would have been working class. This would not in the slightest have determined the nature of the British army or answered Lenin’s questions ‘What class is conducting it? and for the sake of what?’ Nor would – who fired the first shot? – have defined the conflict in the North of Ireland.

The working class British squaddies were fighting for an imperialist army in the interests of their imperialist state just as the Ukrainian workers in the 3rd Assault Brigade are fighting for the capitalist Ukrainian state in its alliance with western imperialism, from whom it will have received its funding, training, weapons and intelligence. That the neo-Nazis within it are not the least bit interested in ‘democracy’ and are bitter enemies of anything remotely resembling socialism just puts the tin hat on the preposterous claims of the social imperialist supporters of Ukraine.

Quotes from Trotsky won’t therefore exculpate today’s social-imperialists who support imperialism while proclaiming socialism. Even the isolated passage quoted at the start of this post assumes an independent working class movement to apply its own seal, but no such movement exists in Ukraine. In raising the demand “Don’t betray Ukraine” the Ukraine Solidarity Campaign has fixed a plus sign to the actions of imperialism where no independent working class movement exists in Ukraine to place its own.

The demand “Don’t Betray Ukraine” is not therefore a call to take advantage of a contradiction within imperialism but to take one side of it instead of opposing both. It is a demand for capitalist solidarity; that one section of it remain united in its struggle against the other. It is a call for Western imperialism to be united in full commitment to a particularly rotten capitalist state, signalling the total abasement of those declaring it.

Back to part 2