I was walking down Buchanan Street in Glasgow on Saturday afternoon when I came across a group that all had large red stickers on them saying ‘Red Tories Out’, which is Scottish nationalist-speak for the Labour Party. The leaflets they were giving out called for a vote for the Scottish National Party so that it could ensure that a new Labour Government was socially just. What on earth is going on?

I was walking down Buchanan Street in Glasgow on Saturday afternoon when I came across a group that all had large red stickers on them saying ‘Red Tories Out’, which is Scottish nationalist-speak for the Labour Party. The leaflets they were giving out called for a vote for the Scottish National Party so that it could ensure that a new Labour Government was socially just. What on earth is going on?

‘Red Tories Out’?? The Labour Party is not in office in Holyrood in Edinburgh and equally obviously not in office in Westminster in London, so what exactly do this group of nationalists want Labour out of? Since they assume (for the sake of their argument) that they are utterly opposed to the real Tories being in power and the only real alternative is the Labour Party, the only answer consistent with their proclaimed strategy is that of no Labour MPs in Scotland but a majority in England and Wales, one big enough to allow their favoured scenario of a Labour Government dependent (or so they want) on SNP support.

No matter how they dress it up the reactionary nationalist logic of division surfaces each time the left in Scotland trumpets its supposedly radical political credentials. The Labour Party is shit; Scots need an alternative but Labour’s good enough for English workers, and we’ll just ignore the fact that we need it as well in order to defeat the hated Tories. But just to show how this isn’t really our strategy we’ll support other parties in England and Wales standing against Labour.

‘Red Tories Out’ turns out to be not just out of Scotland but everywhere. Except if successful this would let the real Tories in as Labour voters supported the Greens and Plaid Cymru, assisting the Conservative Party to capture marginal seats where Labour is the only conceivable alternative.

Of course this would mean that these nationalists wouldn’t be open to the charge of hoping to foist Labour on the English while it wasn’t good enough for them, but then they would have to explain to everyone what’s left of their supposed overriding priority in this election of getting rid of the Tories.

Something in their argument has to give and what gives is their proclaimed support for a Labour Government supported by the SNP. What you see is what you get and when you see ‘Red Tories Out’ stickers it means what it says, no more and no less. When you see aggressive heckling of Labour in a Glasgow street you’re seeing the real vitriolic hatred of the Labour Party.

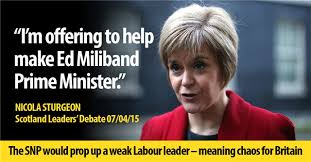

It is the Labour Party that has stood in the way of the SNP objective of ‘speaking for Scotland’; the SNP having some time ago captured swathes of Scottish Tory support. It is a Tory Government in Britain that strengthens their claims that only independence can rid Scotland of the Tories and it just such a Government that would provide the grounds upon which another tilt at separation might be launched.

So the ‘Scottish Sun’ newspaper calls for a vote for the SNP while the English version supports the Tories. The Tories demonise the SNP, making their nationalism more attractive in Scotland in the process, and the SNP ride the wave of increased nationalist division by decrying opposition to their participation in government in England as anti-Scots while basing their whole rationale for existence on the baleful influence of the English.

So it turns out that it is the position of the Sun that is the most consistent of the publicly proclaimed stances – Tories in England and Wales and the Tartan variety dressed in ‘anti-austerity’ clothing in Scotland.

Both on the face of it (‘Red Tories Out’) and looking at underlying political calculation, it is clear that Tory little-Englandism and SNP nationalism is seeking to exploit nationalist division to their own benefit while undermining the causes they say they aspire to – unity of the UK in the case of the Conservative Party and anti-austerity in the case of the SNP.

Reading ‘The Herald’ newspaper on Saturday it reported from focus groups that voters have stopped listening to the political arguments and have bought into the narrative of empowerment, derived from the independence referendum, and the perceived possibility of standing up for Scotland in the General election. ‘No’ referendum voters are therefore voting SNP.

This doesn’t look like a simple unthinking or emotional vote to me but a buying into nationalist assumptions that don’t withstand political analysis and argument. And the most fundamental of these is that there is a ‘Scottish’ interest oppose to that of ‘London’. The conflation of nationalism with the interests of workers allows promotion of nationalism to appear as the promotion of workers’ interests even while it does exactly the opposite.

The double standards and scarcely conscious hypocrisy of the Scottish left are symptoms of this nationalism and an apparent disengagement from political argument an expression of the soporific effect of nationalist illusions.

But it would be wrong to blame the nationalists alone. The Labour Party, that object of nationalist hatred, deserves its own fair share of blame. For a long time it has channelled Scottish workers opposition to what is now called austerity into nationalist and constitutional demands in order to avoid a response based on workers’ own struggles and socialist policies. In this way it could pioneer the conflation of workers’ interests with Scottish interests, when the latter might be seen to be reflected in their own political dominance in the country.

This could be seen in their impotent opposition to Thatcher and support for devolution and now in the appointment of Jim Murphy as Scottish Labour Leader and his proclaiming of the Labour Party as the party best based to fight for Scottish national interests. When it comes to fighting for national interests it’s hard to out-do nationalism. It has taken Ed Miliband to make the most prominent case for workers interests irrespective of nationality.

While over in Glasgow I took in the Celtic match and logged on to a fans blog. One poster derided concerns over the barracking of Jim Murphy while canvassing in Glasgow city centre, saying the guy was a Blairite and had responsibility for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He had blood on his hands and deserved no sympathy.

Fair enough point you might think. As far as it goes. But where is it supposed to go? A bit of shouting and obstruction hardly seems sufficient punishment for mass murder, does it? But what would be appropriate punishment if that was the purpose of the barracking?

Well, for a socialist it is not this or that particular bourgeois politician that is the problem (and certainly not the answer). So the SNP is opposed to ‘illegal’ wars? Is legal mass murder any more acceptable? Does a UN mandate legitimise imperialist murder? Just what sort of alternative is the SNP that the protestors against Murphy support? Just what sort of political mobilisation is it that rallies round a nationalist party whose fiscal manifesto is not essentially different from Labour’s yet considers itself self-righteously anti-austerity?

What matters for the future is building an alternative not only to bourgeois politicians but to the system itself that creates the social basis for these politicians, one which relies precisely on workers lack of engagement in political argument and analysis.

Right now such an alternative requires opposition to nationalist division. It therefore means voting for the best option, given the choices available. A vote for the Labour Party can be justified as one that will provide the best circumstances for fighting austerity, both by virtue of rejecting Scottish nationalist illusions and facing a reduced austerity offensive.

Nationalist separation on the other hand is a counsel of despair, one that asserts that British workers can never fight for an alternative.

- A friend has alerted me to an interview in Jacobin magazine with Neil Davidson, a supporter of Scottish separation, and I will take up the arguments raised by him in a future post.