Raju Das, in an article on ‘The Communist Manifesto’ noted that:

‘Interest in anti-capitalism as well as socialism is growing in many parts of the world. According to a poll conducted in 28 countries, including the United States, France, China, and Russia, 56% agree that “capitalism as it exists today does more harm than good in the world”. A June 2021 poll indicates that 36% of Americans have a negative view of capitalism; this number is much higher among the youth: 46% of 18–34-year-olds and 54% of those aged 18–24 view capitalism negatively. Conversely, and interestingly, 41% of respondents from all ages have a positive view of socialism. This number is higher for the younger people: 52% of 18–24-year-olds and 50% of young adults aged 25–34 have a positive view of socialism. An October 2021 poll shows that 53% of Americans have a negative view of big business . . . The situation outside of the United States within the advanced capitalist world is similar.’

A more recent opinion poll by the magazine Jacobin also recorded promising results on the advance of the idea of socialism in the US. Believing these views can be advanced further by more hate, as we have reviewed in previous posts, is a mistake, not least because it already exists is copious amounts. What is required is clarification and direction, not a greater emotional charge which is unlikely to provide either.

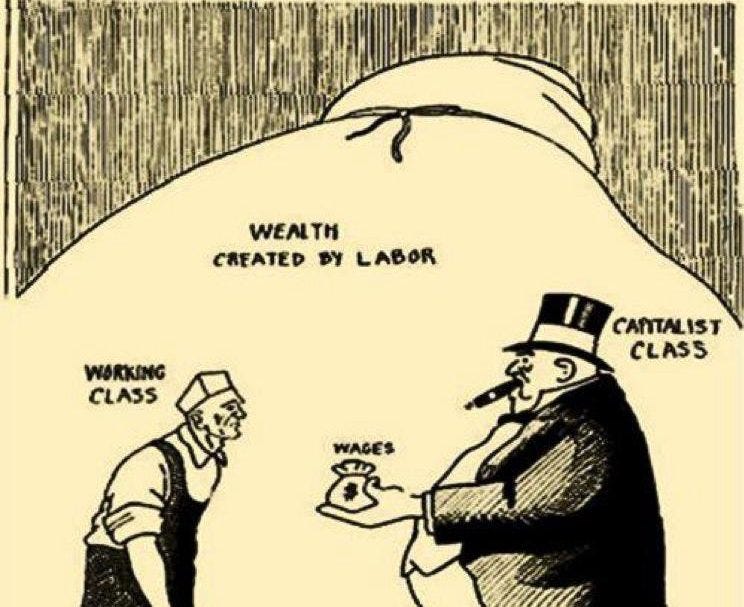

Anger and hatred at the iniquities of capitalism on their own, or even fore-grounded, invite moralistic evaluations that do not in themselves form an understanding of how capitalism can be replaced or the nature of the alternative. The influence of capitalism on the working class, in terms of illusions, pessimism, demoralisation, passivity, and backward ideas, can cause those opposed to it to look for an alternative in various ideas and movements that ignore or reject the working class as the force that can bring about the alternative.

Historically, revolts based on hatred have been the province of peasant rebellions that fail to achieve any lasting change, even in circumstances where they appear to be successful. Provocations by the capitalist state rely on hatred of their regimes in order to suppress developing movements before their time has come; something only clear-headed judgement can hope to determine. Hate is not therefore a distinguishing mark of successful movements and while extreme subjectivism may have become more prominent it is not an answer to objectively unfavourable circumstances or contributory to the working out of strategy.

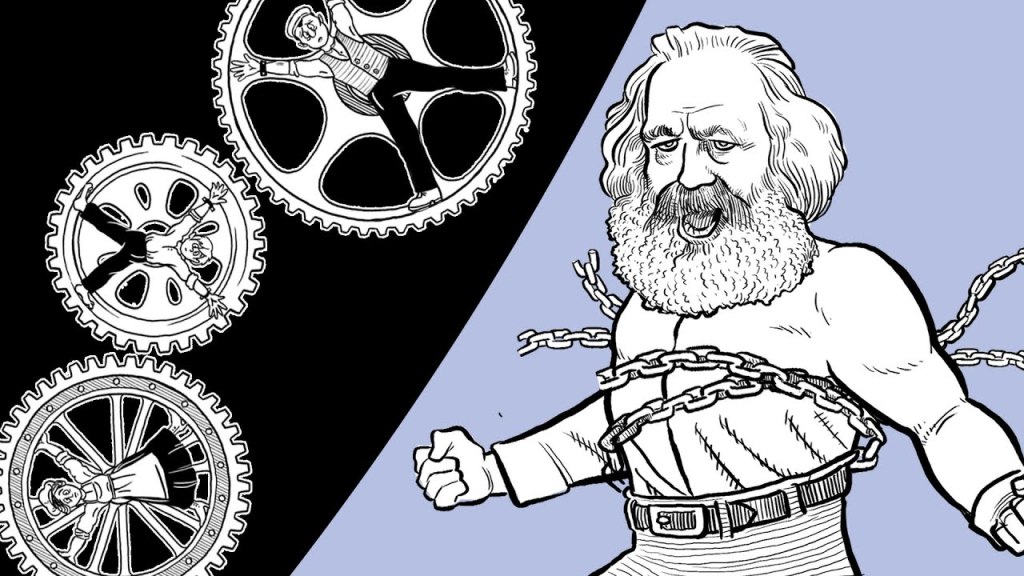

For Marx the primary need for socialist revolution is not so much to overthrow capitalism as to make the working class fit for its own rule – the transformation of the working class so that the economic, social and political system can be transformed. This involves opposition to ideas and practices that divide the working class such as nationalism, racism and sexism but hatred of these should not lead to the belief that these can and must first be completely eradicated within the working class before the building of a working class movement can be commenced or continued.

Marx and Engels stated in ‘The German Ideology’ that ‘Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things’. This includes the existing working class that must make itself capable of creating this movement, which is only possible through struggle, not the assumption that it can come when the class has first purified itself.

Marx had no illusions about the shortcomings of the working class and refused to simply follow it when its actions were antithetical to its long term interests. In the ‘Critique of the Gotha Programme’ written in 1875, he explained the character of society following the capturing of political power by the working class:

‘What we have to deal with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society, which is thus in every respect, economically, morally and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges.’ The working class will itself still be stamped with this birthmark, both ‘morally’ and ‘intellectually’, something that intensifying hatred will do nothing to remedy.

Even alienation, which we looked at before, through which the workings of capitalism disorients and oppresses the working class while also acting to suppress and hide its true nature, has its positive as well as negative character, which more hatred would do nothing to illuminate. As Sean Sayers set out in an article:

Alienated labour ‘is also the process by which the producers transform themselves. Through alienated labour and the relations it creates, people’s activities are expanded, their needs and expectations are widened, their relations and horizons are extended. Alienated labour thus also creates the subjective factors – the agents – who will abolish capitalism and bring about a new society.’

‘Seen in this light, alienated labour plays a positive role in the process of human development; it is not a purely negative phenomenon. It should not be judged as simply and solely negative by the universal and unhistorical standards invoked by the moral approach. Rather it must be assessed in a relative and historical way. Relative to earlier forms of society – strange as this may at first sound – alienation constitutes an achievement and a positive development. However, as conditions for its overcoming are created, it becomes something negative and a hindrance to further development. In this situation, it can be criticized, not by universal moral standards but in this relative way.’ (Sean Sayers 2011, ‘Alienation as a critical concept’, International Critical Thought, 1:3, 287-304).

Advocating greater hatred in order for workers to advance towards greater awareness of their class position assumes it is a pedagogical aid for a politics that is already sufficient for its task. It is not such an aid and the politics sufficient to its objective is still in the process of elaboration.

Karl Marx’s alternative to capitalism part 70

Back to part 69

Forward to part 71