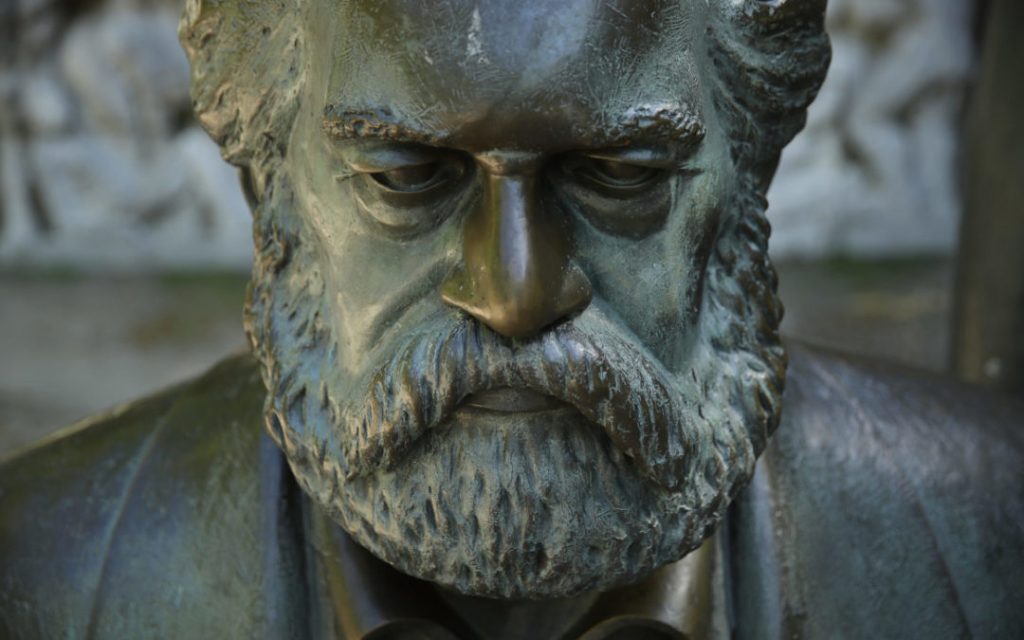

It is ironic that Marx’s idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat is held up as evidence of his authoritarian and oppressive politics when his view was advanced against such conceptions, held by many of his immediate socialist predecessors and contemporaries. These included such figures as the utopian socialist Saint-Simon, Blanqui, Wilhelm Weitling and Ferdinand Lassalle, who are no longer so well known, but whose views are still the staple of many today who are unaware of their ancestry.

In the previous posts on the book Citizen Marx, we noted that early in his political career he was on the extreme democratic wing of republicanism, and against the constraints on democracy supported by liberalism, going much further in identifying the road to a positive conception of freedom. The first ‘dictatorship’ championed by him was the dictatorship of democracy in 1848 during the bourgeois revolutions of that year, which the bourgeoisie betrayed. Such a democratic “dictatorship” would energetically repress any counter-revolution to defend itself from reaction.

For Marx the dictatorship of the proletariat was synonymous with terms that now sound less jarring, such as the ‘political power of the working class’ or the ‘rule of the proletariat’, and meant nothing more nor less than these. In his book Citizen Marx, Bruno Leipold suggests that the various terms Marx used to describe the Paris Commune could also be employed – “Communal Constitution”, “Communal Republic”, “Republic of Labour” and “Social Republic”. What this entailed was set out in the previous post, most particularly the abolition of classes leading to the abolition of the state, understood by Marx as the mechanism for imposing and defending class rule.

As Engels set out, ‘the state is nothing but a machine for the oppression of one class by another, and indeed in the democratic republic no less than in the monarchy; and at best an evil inherited by the proletariat after its victorious struggle for class supremacy, whose worst sides the victorious proletariat just like the Commune, cannot avoid having to lop off at once as much as possible until such time as a generation reared in new, free social conditions is able to throw the entire lumber of the state on the scrap heap.’ (Engels Introduction to Karl Marx’ s The Civil War in France 1Vol 27 p 190)

Marx ventured some views on how the state would develop that history has confirmed:

“The bourgeois state is nothing more than the mutual insurance of the bourgeois class against its individual members, as well as against the exploited class, insurance which will necessarily become increasingly expensive and to all appearances increasingly independent of bourgeois society, because the oppression of the exploited class is becoming ever more difficult.” (Marx, Le Socialisme et l’Impôt, par Emile De Girardin, Collected Works Vol 10 p 333)

Hal Draper, in his third volume of Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, entitled The Dictatorship of the Proletariat ventures that ‘Marx’s term ‘rule of the proletariat’ was reformulated as ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ when Marx had to confront the Blanquist mind. (KMTR Vol III p 293). Draper also notes the comparatively few times – six – that Marx used the term, within two defined periods: 1850–52 and 1871–75. What matters is that it follows from the idea of a working class political struggle, leading to a working class revolution, and new collective property relations based on the working class.

Draper further states that ‘Not before the “Critique of the Gotha Program” and not after it did Marx ever indicate that the party program should include the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, or any formulation involving the word ‘dictatorship’. (KMTR Vol III, p 305)

We have also seen in the posts on Citizen Marx that Marx and Engels believed that a democratic republic provided the best conditions in which to fight for socialism and was therefore more important to the working class than the bourgeoisie. The latter could, if it had to, have its interests defended by dictatorial political regimes that rested on capitalist property relations, while collective and cooperative property relations are inimical to such political forms. Whether the form of the bourgeois state was a bourgeois democratic republic or an authoritarian regime, all entailed the dictatorship of the capitalist class in their understanding of the term since the property relations were capitalist and defended by the state.

As The Communist Manifesto put it “All previous historical movements were movements of minorities, or in the interest of minorities. The proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority, in the interest of the immense majority.”

“The immediate aim of the Communists is the same as that of all other proletarian parties: formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat.”

What distinguished Marx’s conception from that of others was that the “dictatorship” was to be one of the proletariat not over it. As Engels said of one who advanced the latter view:

‘Since Blanqui regards every revolution as a coup de main by a small revolutionary minority, it automatically follows that its victory must inevitably be succeeded by the establishment of a dictatorship—not, it should be well noted, of the entire revolutionary class, the proletariat, but of the small number of those who accomplished the coup and who themselves are, at first, organised under the dictatorship of one or several individuals. (Engels, The Program of the Blanquist Fugitives from the Paris Commune Collected Works Vol 24 p 13)

Emancipation was to be achieved by the working class itself, counterposed to the schemes of the supporters of Blanqui:

‘Brought up in the school of conspiracy, and held together by the strict discipline which went with it they started out from the viewpoint that a relatively small number of resolute, well-organised men would be able at a given favourable moment, not only to seize the helm of state, but also by a display of great, ruthless energy, to maintain power until they succeeded in sweeping the mass of the people into the revolution and ranging them round the small band of leaders. This involved, above all the strictest, dictatorial centralisation of all power in the hands of the new revolutionary government.’ (Engels Introduction to Karl Marx’ s The Civil War in France 1Vol 27 p 188)

This was to be true not only of the workers’ party in relation to society but within the party itself. As Engels put it in a letter in 1890 regarding the German Workers Party: “The biggest party in the empire cannot remain in existence unless every shade of opinion is allowed complete freedom of expression, while even the semblance of dictatorship à la Schweitzer must be avoided.” (Marx and Engels, Collected Works Vol 49 p 11)

Back to part 73