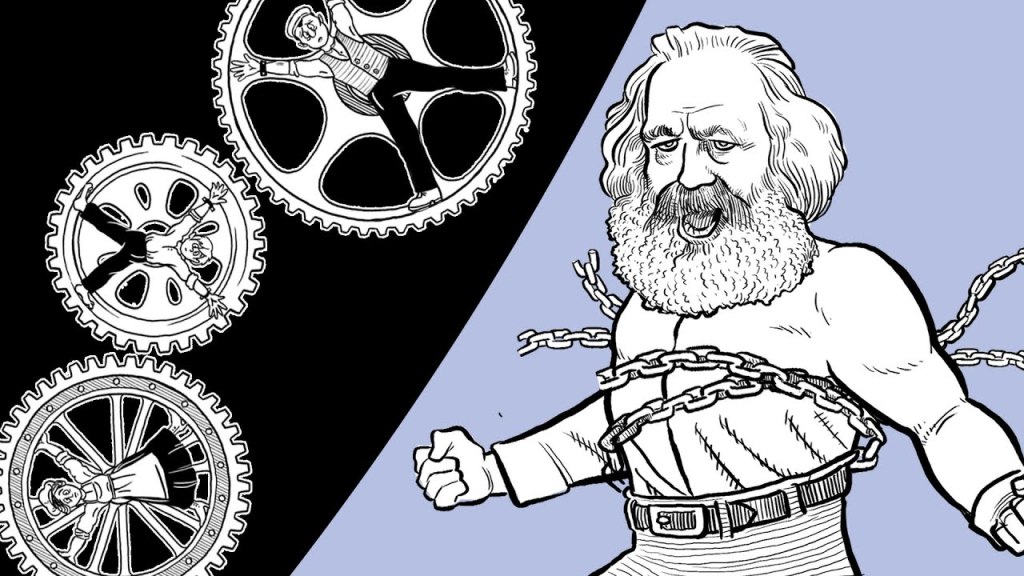

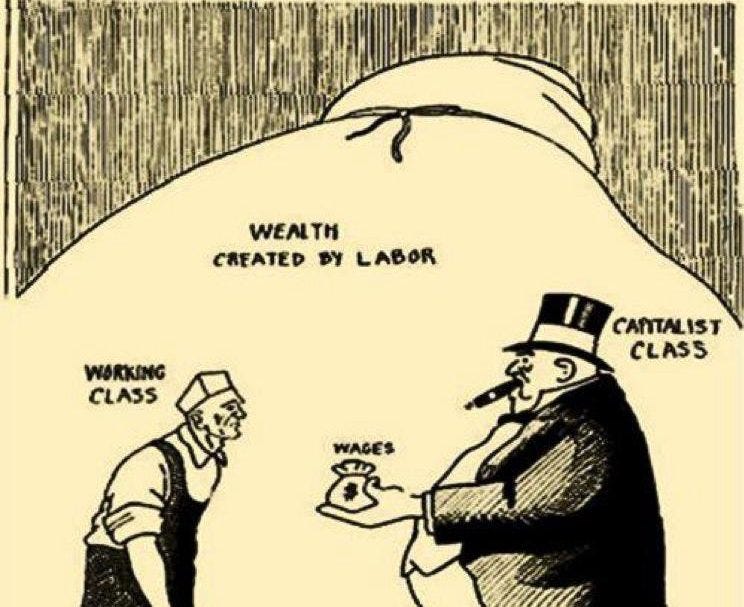

Marxists believe that power in society resides in capital, in the capitalist system and its property relations in which ownership and control of the means of production etc. are monopolised by one class. In the form of money, capital can be otherwise employed to gain political influence through the media, buy politicians and discipline governments through speculation on the bond markets. Capital strikes can disable economies just as individual capitals can close down workplaces overnight destroying the livelihoods of their workers.

On top of this are states that defend these property relations through a multitude of laws bolstered by assumptions about the primacy of bourgeois private property rights that are considered holy writ. Should this be questioned the state is also composed of forces armed with the monopoly of violence to police and impose the requirements of these property relations. Since such relations involve the exclusion of ownership and control by the majority there is nothing democratic about them and no bourgeois claims to democracy entertain the notion that there should be democratic ownership and control of the economy.

Instead such claims to be democratic rely on parliamentary institutions that are dignified with reverential rules and procedures, the better to elevate their status above their essential subordination to the real power in society. Incantations about their sacred embodiment of democracy cover for this subordination while most people vaguely register their awareness of the sham through a view of all politicians as essentially liars.

This, however, is a purely cynical reaction and is not the ground for either an adequate understanding of what is going on or the envisioning of a genuine democratic alternative. Nationalism provides additional glue to bind workers to their (nation) state and the claims it makes for itself on their behalf, but more and more decisions are taken at an international level where real democracy is even more obviously absent. It is generally considered in most of Europe that its people live in a ‘democracy’. The job of socialists is to make them aware that this is bourgeois democracy and that it is a sham that they should seek to change. Moreover they need to be convinced that the state they are invoked to give allegiance to does not defend their interests.

One very small example of the fraudulent character of bourgeois parliamentary democracy has erupted in Ireland as the governing parties have voted to restrict the speaking time of the opposition, reduced its own exposure to questioning, and allocated opposition time to a group of ‘independents’ who have all declared full support for the government and have a number of members as ministers within it. As all the opposition parties have put it, you are either in the government or in the opposition – you cannot be in both.

Dáil sitting has been suspended before in much disorder but was suspended again yesterday when the change in Dáil standing orders was pushed through without debate by the Ceann Comhairle (the Speaker of the House). She is supposed to be independent but was elected as a member of the same ‘independent’ group and appointed as part of the secret deal that no doubt lies behind the speaking privileges now given to it.

This is no doubt a cynical political stoke that should be opposed. The up-its-backside liberal propaganda news sheet ‘The Irish Times’ opined that “normal Dáil business” must “resume immediately” so that a list of issues can be discussed. These include climate and health care that “normal Dáil business” has failed to successfully address for decades. Even these relatively minor attacks on democratic functioning do not find this liberal mouthpiece defending it.

Of course, the government is committing much greater crimes against democracy than these latest shenanigans, including allowing planes delivering arms to Israel to pass through Irish air space. Like governing party claims before the general election about the number of houses that were being built or support for the Occupied Territories Bill, this is a government that cannot be trusted to tell the truth.

The opposition parties, including People before Profit, have united to ‘stridently’ oppose this ‘alarming’, ‘outrageous’ and ‘unprecedented’ plan and to defend the ‘fundamentals of parliamentary democracy’. There has been a lot of talk about the government’s changed procedures reducing their ability to ‘hold the government to account’ and to ‘represent their constituents’.

But this follows People before Profit centring their recent electoral campaign on ending 100 years of unbroken office by the two ugly twins who nevertheless won the recent general election. When has either Fianna Fail or Fine Gael been held to account over this 100 years? When has it been punished for its failures, lies, hypocrisy and previous much more authoritarian measures? In what way do impassioned speeches by People before Profit TDs excoriating government ministers to an almost empty Dáil chamber – shown regularly on social media – embody holding these ministers to account?

The man in the centre of it all,’independent’ TD Michael Lowry, has been found by a state tribunal to be “profoundly corrupt” but here he was giving two fingers to the PbP TD Paul Murphy! Why is he not in jail, never mind inducing the government to tear up Dáil standing orders on his behalf? Tribunal after tribunal has demonstrated that there is no justice from the state and the Dáil chamber is incapable of delivering it either. More evidence of the sham that is bourgeois democracy! Why not say this?

Rather than use the episode to demonstrate this to the Irish working class, to further explain the limits and hypocrisy of bourgeois democracy, and to call out the alternative, People before Profit has decided to become bourgeois democracy’s most vocal defender. Rather than use it as support for the argument that the working class will not find real democracy within a bourgeois parliament, it declares the vital need to support its fraudulent claims that it can allow workers to hold the government to account’, i.e. criticise and punish it. Instead of exposing the hot-air bloviating that passes for democracy it holds out the necessity for extra hours of fine speeches.

Illusions in bourgeois democracy run deep in Irish society, as in most advanced capitalist states, with the continued election of Lowry and the ugly party twins as plenty of evidence. Every opportunity to expose it should be grabbed. Ironically, a previous posture of doing this – of exposing the hollowness of bourgeois democracy evidenced again by this latest stroke – would have been more powerful in embarrassing the government than the strident claims that more time to ask questions and talk to an almost empty room is vital to democracy.

To go back where we started – with Marxist principles. These declare that the emancipation of the working class will come from the activity of the working class itself, a principle precisely counterposed to the parliamentary illusions of much of the left. Real power comes from outside, that of both the capitalist system and of the working class. It is on the power of the working class and its organisations outside that socialists need to focus, and which could do with much greater democratic functioning. Illusions in the Dáil are only for those for whom these illusions are comforting and who seek a career within it.