For some on the left the executive order by Donald Trump that the Federal Government will recognise only two sexes – that gender identity “cannot be recognized as a replacement for sex’, and that it will not replace ‘the biological category of sex with an ever-shifting concept of self-assessed gender identity, permitting the false claim that males can identify as and thus become women and vice versa’ – will be seen as confirming their support for these views. His decision, it will be said, is one from an arch-reactionary who is only being consistent with his other reactionary views.

It is a pity for the holders of such views that their perspective on consistency should lead them to celebrate the progressiveness of the previous Presidential champion of gender ideology, Joe Biden – the sponsor of war in Ukraine and accomplice in the carrying out of genocide in Gaza. The ability of Trump to weaponise simple truths is as much a feature of identity politics as its pernicious role in undermining socialist politics and the primacy of working class unity. The role it has played in the Presidential election and in Western media reports demonstrates the salience of the issue for the health of socialist politics, quite apart from the threat the ideology poses to women’s rights.

I remember, when I was a young teenager and had joined the International Marxist Group, an older gay man telling me that there was nothing inherently left-wing or socialist about being gay and that this was also true of the gay movement. Socialists may have been heavily involved in the fight for gay and lesbian rights, but this has not prevented their incorporation by capitalism into questions of individual identities and attitudes, with no question of structural oppression. In seeking acceptance and equality, capitalist society in many countries has accepted their demands through incorporation on its terms by commodifying them.

The constraints on this incorporation are strict. The UK may have had three women Prime Ministers, but the names Thatcher, May and Truss are hardly symbolic or symptomatic of progress for anything but the most miserable form of feminism. The rotten character of this liberal feminism is demonstrated in its willingness to erase the essential nature of women altogether by prioritising the demands of men who claim to be women. Ireland has had a right-wing gay Taoiseach, and the sectarian arrangement in the North is headed by two women, but belonging to a social group that suffers some form of oppression does not by that fact entail resistance or opposition to the social system that generates it.

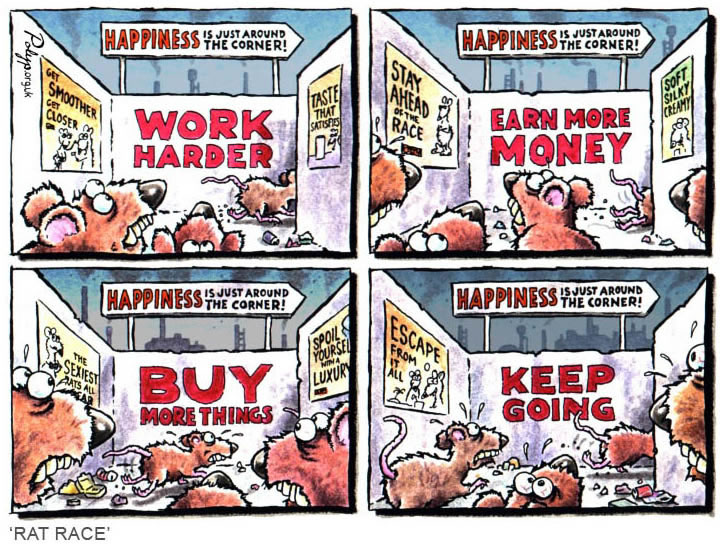

Moves to equal representation under capitalism get you closer to equality, but only equality of exploitation and oppression, which affects the working class, including in its ranks the majority of women, black people, gays, and lesbians. It doesn’t get you anywhere near emancipation or liberation from exploitation and oppression. Identity politics creates division that breeds competition, undermining the grounds for the unity required to remove capitalist exploitation as well as sexual oppression and homophobia.

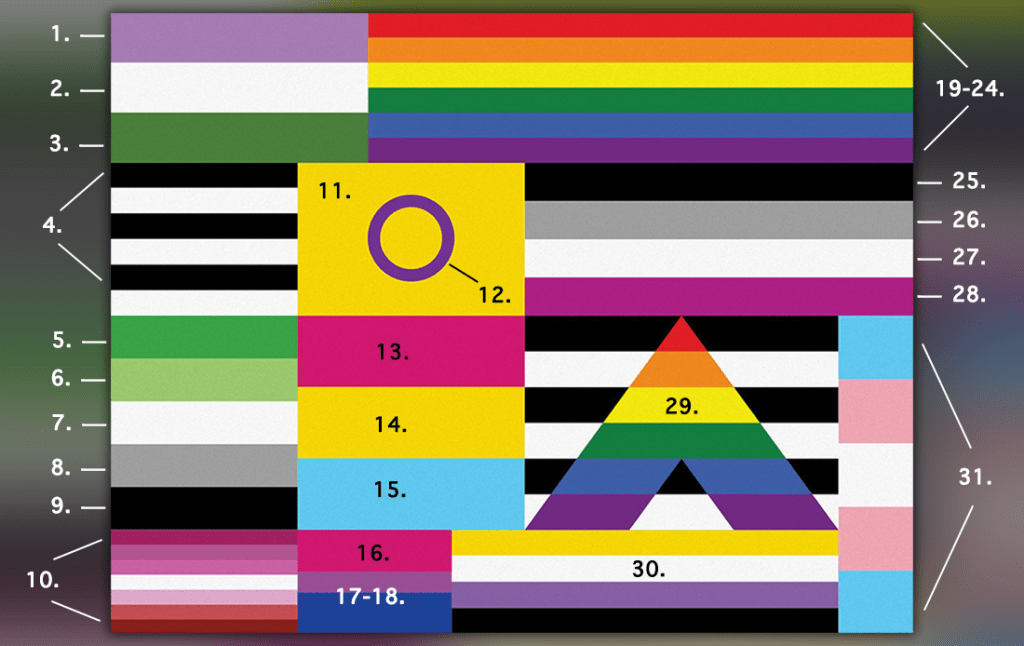

Gender identity ideology is an extreme example of this sort of politics that has commodified sex by pretending that it can be changed while simultaneously denying its centrality. This, for example, removes coherence to any claim to same sex attraction. Ironically, it has done this through attaching its letter to LGB alongside an expanding set of letters – LGBTQQIP2SAA+ – that bear no relation to the initial three, except to cannibalise them, with a + for whatever can be imagined next.

One feminist has described it as akin to religious belief, ‘that trans ideology’s appeal rests on a metaphysical salvation fantasy, that would help explain why it functions far more like a religious cult than a political discourse—and why true believers are so impervious to rational argument and so fond of denouncing heretics and apostates’, ‘the primacy of gender identity would then express the drive to transcend bodily limitation analogous to the thought of The Resurrection’. (Jones, Jane Clare. The Annals of the TERF-Wars and Other Writing (p. 351-2). Kindle Edition.)

While this may be true of some adherents and provides clear parallels of the ideology with religious belief – based on faith and not material reality – it does not explain its attraction to the left in more secular western societies. Ironically, the more religious, with traditional views of sexuality, are less prone to swallow it because they recognise that their conservative sexual norms apply to real sexes.

Instead, the vulnerability of certain sections of the left to gender identity ideology is due to their abandonment of socialist politics based on the material world and their flight into a more congenial and comforting world of moralistic claims, of good and bad, to be addressed through the assertion of rights to be imposed by the state. The liberal left now dominates as its natural home is the state, which provides the environment of NGOs and other state-funded organisations that substitute for the working class movement as the agent of radical change. The long-standing view that the state can embody socialism eases the journey to this destination even of it does not make it inevitable.

Identity politics is a world of the sanctity of self-identity (no matter how detached from reality); of self-determination of the individual (how is this possible and what does it permit or not permit?); of the claims of the oppressed and their ‘lived experience’ (what other kind is there?); with an absolute value placed on ‘inclusion’ and absolute exclusion of ‘exclusion’. The solipsism involved prevents the liberal left responding in the standard way to the claims of the religious – that extraordinary claims demand commensurate explanations – and instead pronounce the empty and ignorant mantra of ‘no debate’. It forgets that freedom of religion also requires freedom from religion just as the freedom to associate requires the freedom not to associate. The freedom for women to associate also requires their freedom not to associate with men, those ‘identifying’ themselves as women or not.

Politics based on moral values free from actual struggle can find its grounding on the claims of oppressed groups, irrespective of their politics, based simply on the fact that they are oppressed, or claim to be. No need to elaborate theories or political programmes that analyse oppression, ground it on an analysis of material conditions, seek to learn from historical struggles and test alternatives in debate.

When these struggles do not exist, or have not existed for some time, or have been defeated, and thus do not impose their requirements on participants, all this is unknown – especially to generations in which mass working class struggle is largely history. Hence the attraction to youth, highlighted by the generational divide over gender identity ideology, and the noteworthy fact that this ideology has flourished especially, although no longer solely, in English speaking Western countries where working class struggle has suffered long term defeats. In such reactionary periods reactionary ideas take hold, and this is one.

Unfortunately, the experience of some countries in Latin America illustrates its compatibility with left presenting regimes accommodating reactionary policies, such as gender ideology in the constitution of Ecuador and Bolivia and legislated in Argentina and Brazil, while in all except Argentina legal abortion is not allowed. In the latter it was introduced in 2020 for ‘pregnant people’, while women became a ‘gestating person’. (Women’s Rights, Gender Wrongs p66 and 68)

That the left is identified with this ideology is one more piece of alien baggage it will have to discard and to do so not by ignoring it but by exposing and defeating it.

Back to part 7