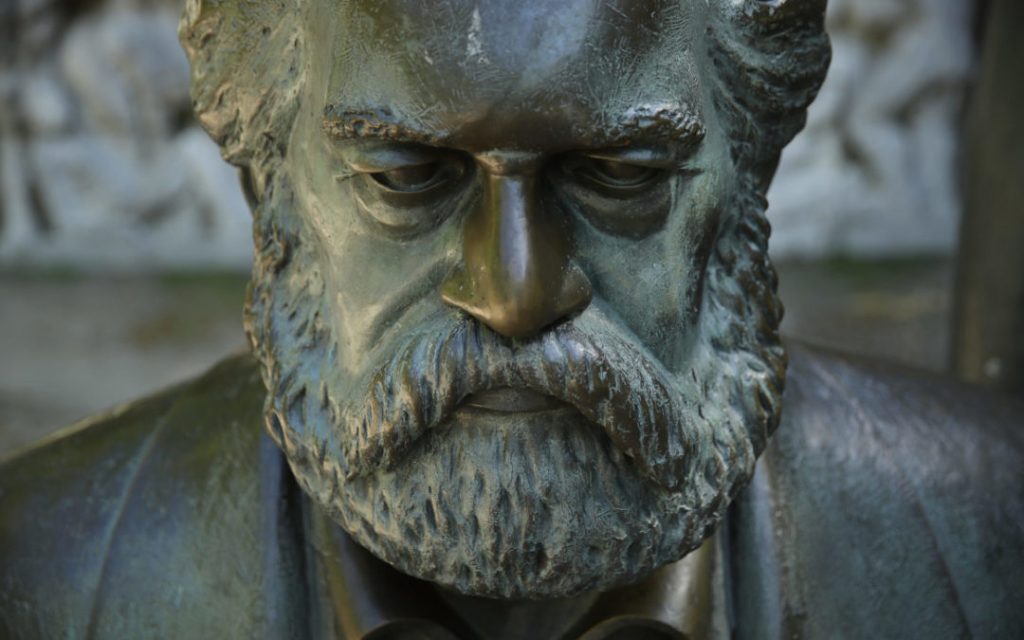

“Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.” (Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme, Collected Works Vol 24 p 95)

The qualitatively greater degree of freedom to which the dictatorship of the proletariat is directed is explained firstly by Marx’s opposition to the idea of a “free state”: “Freedom consists in converting the state from an organ superimposed upon society into one completely subordinate to it, and even today forms of state are more free or less free to the extent that they restrict the “freedom of the state.”

The mistaken view of the state as the mechanism that can bring about freedom arises from the view that instead “of treating existing society (and this holds good for any future one) as the basis of the existing state (or of the future state in the case of future society), it treats the state rather as an independent entity that possesses its own “intellectual, ethical and libertarian bases”. (Critique of the Gotha Programme) This false idea is today more or less widespread among many ‘Marxists’ who champion nationalisation, ‘the public sector’, income redistribution and welfarism, or ‘national sovereignty’ and ‘self-determination’.

The basis of the state under the dictatorship of the proletariat is the development of cooperative economy to the national level and beyond so that society as a whole becomes a cooperative venture consciously moulded to human need by being consciously planned. Capitalism begins this transition through its socialisation of production but only by raising its contradictions to a higher level while cooperative production begins its positive supersession.

This development within capitalism, however, cannot be adequate or sufficient to achieve its replacement, as Marx explained: “Restricted, however, to the dwarfish forms into which individual wages slaves can elaborate .. by their private efforts, the co-operative system will never transform capitalist society. To convert social production into one large and harmonious system of free and co-operative labour, general social changes are wanted, changes of the general conditions of society, never to be realised save by the transfer of the organised forces of society, viz., the state power, from capitalists and landlords to the producers themselves.” Marx Instructions for the delegates of the Provisional Geneal Council, Collected Works Vol 20 p.)

If the road to socialism can loosely be called rule by the working class Marx explains more clearly the steps which the dictatorship of the proletariat must take upon the conquest of political power (which, to emphasise, is inseparable from social power more generally): “What we are dealing with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society, which is thus in every respect, economically, morally and intellectually, still stamped with the birth-marks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society—after the deductions have been made—exactly what he gives to it.”

Marx explains that in these “altered circumstances no one can give anything except his labour, and . . . on the other hand, nothing can pass to the ownership of individuals except individual means of consumption.” The accumulation of capital by a minority class, and therefore also a class that must work on its behalf, cannot arise, so that with this “abolition of class distinctions all social and political inequality arising from them would disappear of itself.” (Critique of the Gotha Programme, Collected Works Vol 24 p 96 & 92)

This must lead ultimately “In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labour, and thereby also the antithesis between mental and physical labour, has vanished; after labour has become not only a means of life but life’s prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-round development of the individual, and all the springs of common wealth flow more abundantly—only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs!”

Not only did Marx and Engels put forward this prospectus, but they lived long enough to see an initial attempt to begin it, if only in a very limited fashion – in one city, for a short time, and by an undeveloped working class still short of full consciousness of its task:

“Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat”. (Engels) “The political rule of the producer cannot coexist with the perpetuation of his social slavery. The Commune was therefore to serve as a lever for uprooting the economical foundations upon which rests the existence of classes, and therefore of class rule.” (Marx, The Civil War in France, Vol 22 p334)

“ . . the present “spontaneous action of the natural laws of capital and landed property”—can only be superseded by “the spontaneous action of the laws of the social economy of free and associated labour”, by a long process of development of new conditions, as was the “spontaneous action of the economic laws of slavery” and the “spontaneous action of the economical laws of serfdom”. “But they know at the same time that great strides may be taken at once through the Communal form of political organisation and that the time has come to begin that movement for themselves and mankind.” (Marx, The Civil War in France, Vol 22 p491-2)

“Its true secret was this. It was essentially a working-class government, the produce of the struggle of the producing against the appropriating class, the political form at last discovered under which to work out the economical emancipation of Labour.” (Marx, The Civil War in France, Vol 22 p334). This “economical emancipation of Labour” was thus to be ‘worked out’ by the working class itself, not by the new state or its governmental executive, but ‘under’ a ‘political form’ that obviously would require organisations of the working class separate from the state, even its own workers’ state to carry out this task..

The new relations of production, which it is the role of the workers’ state to defend, are the means by which the collective and associated labour will develop “by a long process” towards socialism: t”he superseding of the economical conditions of the slavery of labour by the conditions of free and associated labour can only be the progressive work of time.” (Marx, The Civil War in France, Vol 22 p 491)

This, in practice, and not just in theory, demonstrated the wholly democratic credentials of proletarian dictatorship in its earliest form. In order to avoid bourgeois political corruption, Engels claimed that “the Commune made use of two infallible expedients. In this first place, it filled all posts—administrative, judicial, and educational—by election on the basis of universal suffrage of all concerned, with the right of the same electors to recall their delegate at any time. And, in the second place, all officials, high or low, were paid only the wages received by other workers. The highest salary paid by the Commune to anyone was 6,000 francs. In this way an effective barrier to place-hunting and careerism was set up, even apart from the binding mandates to delegates to representative bodies, which were also added in profusion” (Engels, postscript to The Civil War in France, Collected Works Vol 27 p190)

Back to part 72

Forward to part 74