Like all organisations, the state’s abiding interest becomes its own preservation and health, which interests are separate from that of society. So a new society still marked by commodity production, “just as it emerges from capitalist society, which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges”; it cannot be assumed that the interests of the workers’ state will not be inimical to some degree with that of society–or the working class–as a whole. It was steps taken by the Paris Commune to address this that received affirmation from Marx and Engels, even if these were incomplete.

Marx noted that all previous revolutions perfected the state, unlike working class revolution that will seek to break its capitalist form, with the abolition of classes consequently meaning that there is no requirement for its existence–the organisation of the domination of one class by another would become redundant. The dictatorship of the proletariat would itself disappear as there would be no proletariat.

‘One of the first decisions of the Paris Commune was replacement of the standing army and police. The Commune made that catch-word of bourgeois revolutions, cheap government, a reality, by destroying the two greatest sources of expenditure—the standing army and State functionarism. Its very existence presupposed the non-existence of monarchy, which, in Europe at least, is the normal incumbrance and indispensable cloak of class-rule. It supplied the Republic with the basis of really democratic institutions. But neither cheap government nor the “true Republic” was its ultimate aim; they were its mere concomitants.’ (Karl Marx The Civil War in France, Collected Works Vol 22 p 334)

What Marx envisaged after the achievement of the political power of the working class was the abolition of the state – as a mechanism of class rule – along with the classes that made it necessary. This would not happen immediately, but neither did it involve the massive expansion of the state and its role, under the claim that the class struggle would intensify as later claimed by Stalinism. Instead the rule of the working class would increasingly involve the takeover of functions previously carried out by the state by society itself.

This would take some time; the working class “know that in order to work out their own emancipation, and along with it that higher form to which present society is irresistibly tending by its own economical agencies, they will have to pass through long struggles, through a series of historic processes, transforming circumstances and men.” (Karl Marx The Civil War in France, Collected Works Vol 22 p 335)

The idea that it is the state that would free the working class was therefore alien to Marx and Engels’ politics, never mind the bloated and parasitic place it had in the Stalinist states of the 20th century. While the workers’ state would deploy political power to defend the collective property of the working class, like all states it would rest on this form of property itself and upon which the working class would in turn base its social power, with the state subordinated to it, ‘not the master but the servant of society’. In any other circumstances the view of both men – that the state would die away – would be impossible, something confirmed by the experience of the Stalinism in the following century.

“When at last it becomes the real representative of the whole of society, it renders itself unnecessary. As soon as there is no longer any social class to be held in subjection; as soon as class rule, and the individual struggle for existence based upon our present anarchy in production, with the collisions and excesses arising from these, are removed, nothing more remains to be repressed, and a special repressive force, a state, is no longer necessary. The first act by virtue of which the state really constitutes itself the representative of the whole of society – the taking possession of the means of production in the name of society – this is, at the same time, its last independent act as a state. State interference in social relations becomes, in one domain after another, superfluous, and then dies out of itself; the government of persons is replaced by the administration of things, and by the conduct of processes of production. The state is not “abolished”. It dies out (Engels Anti-Duhring Vol 25 p268). The state does not therefore become the agent of transformation but “dies out” as this is achieved.

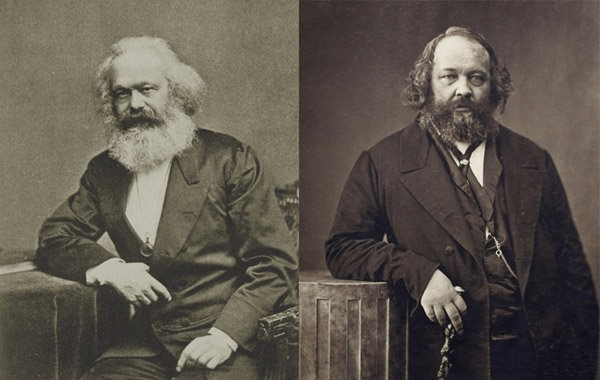

In some marginal notes, in the form of an imaginary conversation, Marx criticised the book Statism and Anarchy by the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, throwing more light on what was meant by abolishing the state:

Bakunin – “If there is a state [gosudarstvo], then there is unavoidably domination [gospodstvo], and consequently slavery. Domination without slavery, open or veiled, is unthinkable — this is why we are enemies of the state. What does it mean, the proletariat organized as ruling class?”

Marx – “It means that the proletariat, instead of struggling sectionally against the economically privileged class, has attained a sufficient strength and organisation to employ general means of coercion in this struggle. It can however only use such economic means as abolish its own character as salariat, hence as class. With its complete victory its own rule thus also ends, as its class character has disappeared.”

Bakunin – “Will the entire proletariat perhaps stand at the head of the government?”

Marx – “In a trade union, for example, does the whole union form its executive committee? Will all division of labour in the factory, and the various functions that correspond to this, cease? And in Bakunin’s constitution, will all ‘from bottom to top’ be ‘at the top’? Then there will certainly be no one ‘at the bottom’. Will all members of the commune simultaneously manage the interests of its territory? Then there will be no distinction between commune and territory.”

Bakunin – “The Germans number around forty million. Will for example all forty million be member of the government?”

Marx – “Certainly! Since the whole thing begins with the self-government of the commune.”

Bakunin – “The whole people will govern, and there will be no governed.”

Marx – “If a man rules himself, he does not do so on this principle, for he is after all himself and no other.”

Bakunin – “Then there will be no government and no state, but if there is a state, there will be both governors and slaves.”

Marx – “i.e. only if class rule has disappeared, and there is no state in the present political sense.”

Bakunin – “This dilemma is simply solved in the Marxists’ theory. By people’s government they understand (i.e. Bakunin) the government of the people by means of a small number of leaders, chosen (elected) by the people.”

Marx – “Asine! This is democratic twaddle, political drivel. Election is a political form present in the smallest Russian commune and artel. The character of the election does not depend on this name, but on the economic foundation, the economic situation of the voters, and as soon as the functions have ceased to be political ones, there exists 1) no government function, 2) the distribution of the general functions has become a business matter, that gives no one domination, 3) election has nothing of its present political character.”

(Marx, Conspectus of Bakunin’s Statism and Anarchy, Collected Works Vol 24, p518-519)

In response to Bakunin’s argument that a worker, once elected to a post, ceases to be a worker and becomes only a bureaucrat seeking his own aggrandisement, Marx refers to “the position of a manager in a workers’ cooperative factory”. A social authority therefore will still exist but with the existence of collective and cooperative relations of production; the end of the need for the suppression of antagonistic class relations and generalised social equality; the political role as performed by the newly formed (and today by the existing capitalist state) will “die out”. The workers’ state must therefore have a very different dynamic than today’s capitalist one – to shrink and decline rather than expand and grow.

The dictatorship of the proletariat is therefore not a dictatorship in the currently understood sense of that term but is a period of development of society in which the rule of the majority, of the working class, leads to the dying out of the mechanism that makes such a dictatorship possible – the state. The Paris Commune, celebrated by Marx was, he said, a “revolution against the state itself.”

Back to part 74

Forward to part 76