The widespread revulsion among many in the West at the genocide in Gaza explains the increasing clampdown by governments on protests against it. These tend towards opposition against the Western states themselves, whose complicity is too obvious to hide, while the attempts to disguise and justify it by the likes of the BBC etc. reduces their influence.

This comes at a difficult time when Western political and military leaders and their propagandists in the media announce that the populations of the West should be preparing for war themselves. The latest is a report stating that:

‘The European Commission should facilitate the prolongation of the conflict in Ukraine in order to contain Russia and prepare for war within the next five years. European Commissioner for Defence Andrius Kubilius made such a statement during the annual conference of the European Defence Agency in Brussels.’

“Every day that Ukraine continues to fight is another day for the EU and NATO to become stronger,” he said, calling on European countries to “prepare for war in the next five years” and to move the European economy to ” turbowarfare regime”.’

“We should spend more on weapons, produce more and have more weapons than Russia,” Kubilius added.’

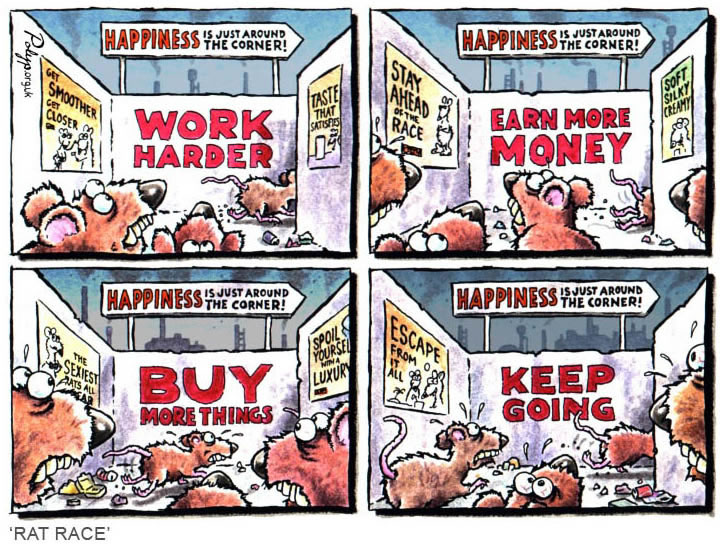

This is the inescapable logic of all those, from the right to the pro-war left, who currently support the war. It follows from their claims that Ukraine must be supported because it is fighting for democracy – for ‘us’ – against an aggressive imperialism. If it is acceptable for Ukraine to ally with NATO and for workers in the West to support it in doing so, then the same Russian threat exists not only to Ukraine but also to Eastern Europe. After all, is this not the inevitable course of an aggressive imperialism? If this imperialism threatens Eastern Europe only the stupid could deny that the same threat would then not also be posed to Western Europe.

So far, some groups like that promoted by Anti-capitalist Resistance are committed to this view in relation to Eastern Europe; but a war they believe can spread from Ukraine to Eastern Europe has, for similar causes, no rationale not to spread from Eastern Europe to Western Europe. This means that there is no reason not to support their own states in this future war and accept the preparations necessary to fight it, those demanded by the EU Commissioner for Defence.

Since most of the Western left has failed to oppose the war it is therefore politically disarmed against the bellicose demands for rearmament by their own capitalist states. This is true both of those who pretend that the war by Ukraine is one of national liberation and of those who believe it is an imperialist proxy war and a war of national liberation at the same time. The latter simply import into their position the contradiction that the real world outside damns in the former.

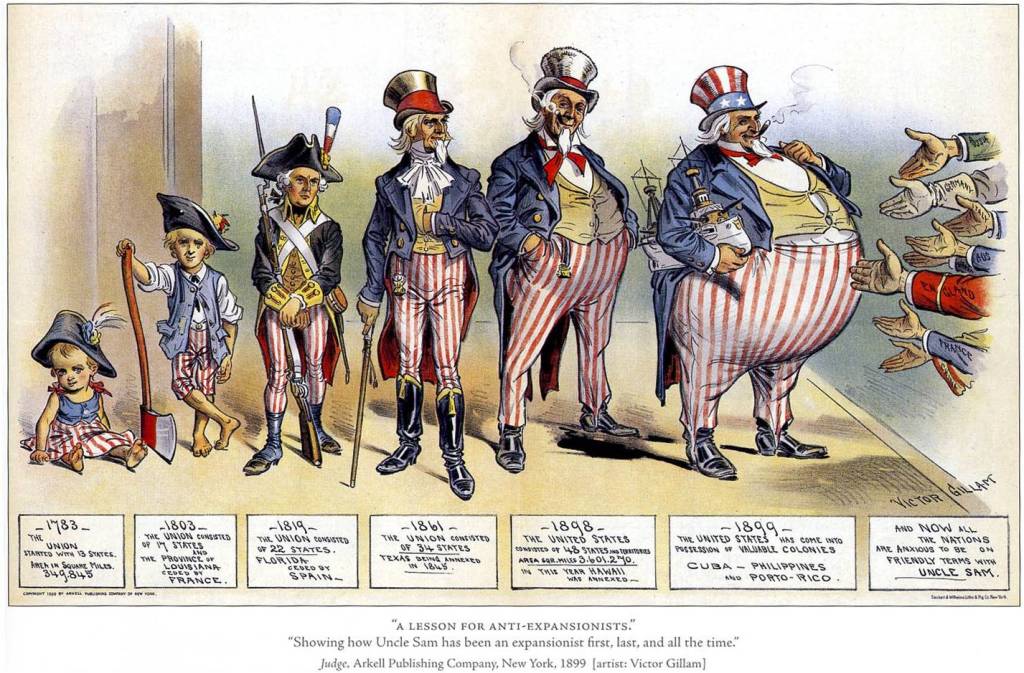

Now, along comes Donald Trump to make it clear that imperialist rivalry really is aggressive by its nature, including the Western variety. The attempt therefore to claim that it is the Russian variety that is solely responsible for war must explain in what way it is not just one instance of a world-wide phenomenon; why the expansion of NATO to include Ukraine is not central to the cause of the war; why Ukraine should be supported when its criticism of Israel has been that it hasn’t provided it with weapons – something now being rectified; why support should be given to the Western variety of imperialism when it is participating in genocide in Palestine; and most importantly, why opposition to the invasion requires support for the alliance of Ukraine and Western imperialism.

Of course, the pro-war left opposes Trump, but more as an anomaly – rather like others in the bourgeoisie media – who will highlight the differences but ignore the continuities with the previous Biden administration. However, some of these commentators have already admitted that what stands out about Trump is his open espousal of the same principles as his predecessors without the hypocritical rhetoric that has usually accompanied it. He is as much a product of Western bourgeois democracy that the pro-war left defends as the Obamas and Bidens.

Trump’s threat of ethnic cleansing will compete against Biden’s genocide for barbarity. Sanctions and creeping economic war against China started under Trump but were maintained and expanded by Biden. Trump’s threat to make Europe pay for the war in Ukraine follows Biden’s existing imposition of its costs on Europe through sanctions, blowing up European infrastructure, and selling it more expensive energy and lots of US weapons.

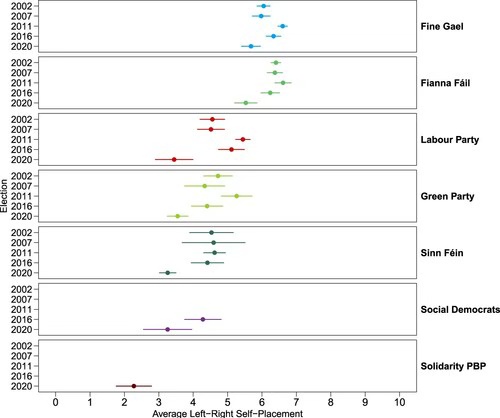

Trump is evidence of there being more than one way to pursue US primacy. Of course, this doesn’t mean there isn’t a difference, but it is necessary not to limit opposition only to them. The petty bourgeois character of the left is exposed by its seizing on such differences to drop principled opposition to other bourgeois forces and ally with them in opposition to what is called the far-right or fascism. This includes the same forces whose rule led to the growth of the far-right in the first place. We see this process again and again in support for the Democrats in the US, Macron in France, and Starmer’s Labour Party in Britain. In Ireland it is Sinn Fein that is supposed to be central to a left alternative despite its record in office in the North of the country.

All these have failed, or will fail, because these forces are not an alternative to what is called the far-right, which in many cases is just the further right. These far-right formations represent, or are composed of, the reactionary sections of the petty bourgeoisie with their narrow nationalist ideas that must inevitably under current conditions gravitate to those they seek to replace, or shift their ground to achieve the same outcomes with different methods. The accommodation that many so-called centrist bourgeois formations are making with the far-right should be all the evidence needed that the dividing line is not some notion of a more and more discredited bourgeois democracy against right wing populism and authoritarianism but between the working class and the bourgeoisie that is attempting to conscript it for war and get it to pay the price in money and blood.

Forward to part 2