Covert action has been a favoured means of waging war since at least the start of the first Cold War, with such covert action often part of what has been variously termed vicarious or proxy warfare. It has been used by Empires for a long time, employing the resources of their conquests, such as the British with Hindu Sepoys, Nepalese Gurkhas and the French with Algerian Berber Zouaves. In the middle of the 19th century Britain ruled India with almost 278,000 troops of which only around 45,000 were European

From the Truman administration onwards the typical US intervention into other countries has also involved economic and financial sanctions, with the proxy element involving the demand that third countries implement these measures as well. These are usually followed by clandestine or ‘special’ operations and then conventional war; the preferred agency of the CIA thus became involved in over 900 major covert actions between 1951 and 1975.

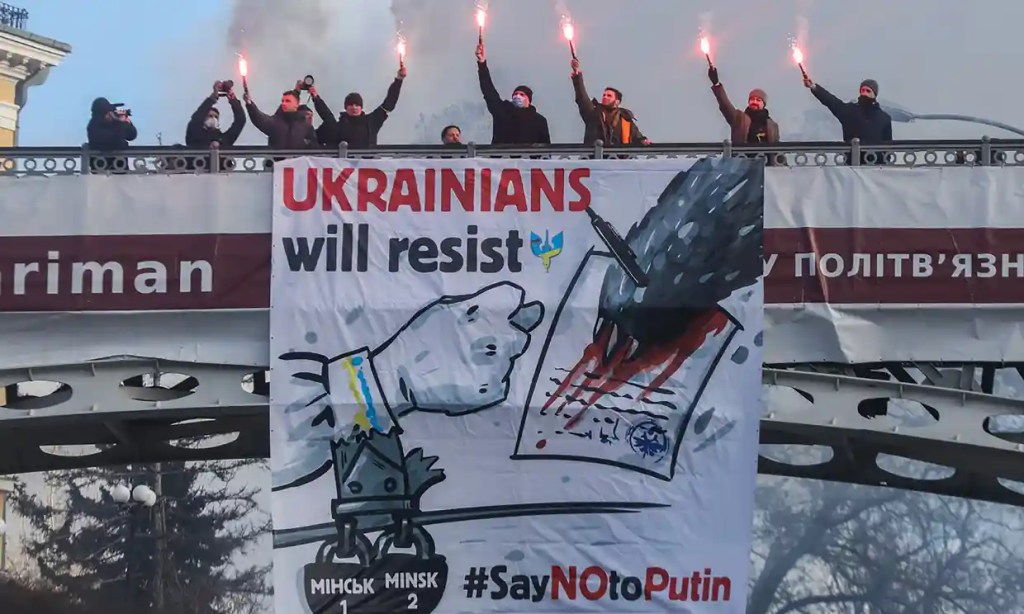

The supposed advantage of this approach is that it is less expensive in terms of money, troops and political capital. The proxy war being waged by US imperialism today shows all these features except on a much larger scale. Almost an entire, and relatively large, country is being employed as a proxy – unless one believes that the US is really concerned with the independence of the Ukrainian state and not the significant degrading of Russia. The US has demanded that every other country impose its economic and financial sanctions even to the point of incurring massive damage to their own economies.

While proxy wars are supposed to be less expensive the sheer scale of this one involves massive cost, which however is incurred unequally. The arms and energy industries, especially in the US are doing just fine. Massive political propaganda has improved the political position of US imperialism, at least in the West, including the subordination of much of what passes for the Left in these countries, so that in this respect as well the proxy war has fulfilled its function. Whether this continues to hold good is another matter.

The first Cold War appeared to make direct war between the US and Russia unthinkable because of the risk of nuclear escalation, but the US has sought counterforce and nuclear primacy strategies that would supposedly make a nuclear war winnable in some meaningful sense. The potential escalation involved in this proxy war is therefore greater than previous conflicts.

* * *

In a review of three books on proxy warfare In the London Review of Books Tom Stevenson notes that ‘America is the world’s most prolific sponsor of armed proxies’ and that it ‘has done most to develop the proxy war doctrine. In January 2018 the US military introduced the ‘by-with-through’ approach. It was the work of J-2, the intelligence directorate of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: ‘the US military must organise, resource and train’ local forces and ‘operate by, with and through’ its ‘partners’ and ‘nations that share our interests’ (note that the word ‘proxy’ is avoided in favour of more anodyne terms). Using proxies has been common practice for the CIA for decades, but the J-2 doctrine describes an increasingly common style of war.’

He noted when writing (in the second half of 2020) that ‘around half the US troops in Afghanistan are technically mercenaries: they are deployed for private profit.’ In Iraq in 2008 the US had a proxy army of 103,000 ‘Sons of Iraq’ fighting in Anbar. In Afghanistan the US trained over 50,000 mujahedeen, providing nearly $3bn in aid between 1979 and 1989. As the CIA Director William Casey put it: ‘Here’s the beauty of the Afghan operation . . . Usually it looks like the big bad Americans are beating up on the little guys. We don’t make it our war . . . All we have to do is give them help.”

The current war has been precipitated by Ukraine seeking to formally join NATO while securing the approval of US imperialism for its security strategy aimed at the conquest of the Crimea, which Russia considers its own territory. Nancy Pelosi, before the provocative visit to Taiwan, said after a visit to Kyiv and a meeting with President Zelensky, that America stands “with Ukraine until victory is won.” US defence secretary Lloyd Austin said “we want to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.”

US objectives are therefore not limited to those internal to Ukraine but to requirements in relation to Russia, its economy and security, and the balance of power between it and both Russia and China, to which the US quickly turned its sights on the pretext of the Ukraine war. There can be no doubt that the amount of military aid provided by western imperialism has materially affected the dynamics of the war with the effect of turning almost the whole of Ukraine into a proxy for its own interests.

Since these interests are truly world-wide the potential for a global conflict is obvious, even the pro-war left acknowledges this danger while cheerleading Ukrainian armed forces. This awareness does not translate into opposition to the war itself but only to the imposition by the US and NATO of a no-fly zone over Ukraine and the open introduction of their troops on the ground.

It appears therefore that the only inter-imperialist war that can exist for this Left is one that creates the immediate potential for a nuclear exchange. This currently has the effect of allowing an underestimation of the potential for this happening through anything short of direct kinetic combat. Even the right-wing RAND corporation presents scenarios in which US intervention can trigger direct warfare with the potential use of nuclear weapons. Others were noted in the previous post.

It has been argued that there has been no nuclear war between the United States and Russia because conventional war between them is also inconceivable. Except that it has reasonably also been suggested that direct conventional war between them has not occurred because no conflict between them has occurred that has involved the vital interests of both, and from which therefore neither can retreat.

NATO membership of Ukraine, with the possibility of stationing long-range missiles within a short distance from Moscow, coupled with an avowed policy of a direct conventional attack on territory claimed to be part of Russia containing its Black Sea fleet, would obviously seem to involve vital strategic Russian interests. That this scenario has precipitated aggressive Russian action can be a surprise to no one. To pretend therefore that only Russia is responsible for this war lacks any credibility.

Russia has time and time again warned that Ukrainian membership of NATO is a red line. Putin in 2008 ,after the summit in which NATO declared Ukraine would become a member, said that “we view the appearance of a powerful military bloc on our borders . . . as a direct threat to the security of our country.”

It does not matter whether Russian action is morally reprehensible and should be condemned. It is not the job of socialists to right the moral wrongs of world capitalism and the states that it comprises. The job of socialists is to argue and fight for a new society in which such wrongs are abolished, and this means starting from current society and seeking how it can be changed. This is the subject of the long series of posts on this blog on Marx’s alternative to capitalism (here for example), which relies on the independent social and political organisation of the working class across the world supported by other oppressed and exploited classes and layers of the population.

This will not be done by defending the prerogatives of capitalist states on the grounds that they have provoked invasion by other bigger capitalist powers, or the idiot view that we should defend their right to join imperialist military alliances. We should oppose both the Russian invasion and the participation of western imperialism because only this identifies the sources of the war and the enemies of workers suffering from it directly and indirectly.

Gilbert Achcar of the Fourth International says that the war in Ukraine is not an inter-imperialist war because such a war ‘is a direct war, and not one by proxy, between two powers . . .’ In the last couple of decades the phenomenon of imperialist proxy wars has had a resurgence and the most significant wars of the last few decades have all been proxy wars of one variety or another, either originating or developing as such, including Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya and others.

It does indeed matter that US and NATO imperialism is not attempting to impose a no-fly zone or placing large numbers of troops on the front-line but refusal to call this an inter-imperialist proxy war has led to a position in which the actions of US/NATO imperialism is supported (through supply of arms) and the actions of the reactionary proxy (the Ukrainian state) are openly celebrated.

The war in Ukraine has brought the proxy mode of war increasingly adopted by imperialism to a new level, not only because of the scale of the war and the military support provided, not only because the proxy is a large state and is directly fighting Russia and not some Russian proxy, but because it involves the perceived vital interests of Russia. We need only consider the response of US imperialism if Russia was pouring weapons into an anti-US Mexico that had declared its intention to reconquer Texas to appreciate the view of the Russian capitalist state. We can now see the provocation involved by successive reactionary Ukrainian governments including putting the objective of NATO membership into the constitution guided by an increasingly ultra-nationalist ideology.

Understanding that what we are seeing is an imperialist proxy war leads us to oppose both US imperialism and the Russian state and in doing so strengthens the independent political position of the working class. If the road to freedom lies in appealing to the assistance of either US imperialism or Russia the working class will never learn to look to itself.

Back to part 5