Fragments makes a series of observations about the political consciousness of the Irish working class, some of which we have already noted, such as the view of many on the Labour Party entering office that ‘the crisis was clearly not their fault and . . . the harsh austerity measures they took were seen as both forced by the Troika and, while painful, necessary.

It records the view of another author that the first year of crisis saw a large number of demonstrations but these ‘dried up once the public realised the magnitude of the banking crisis, and they were replaced by years of “muted protest”. Certainly, there was a sense of powerlessness at the scale and suddenness of the economic crash, a degree of acceptance of the official narrative . . .’ (p31)

It notes that the muting of protest was partially the result of emigration, particularly of the young with 106,000 leaving from 2009 to 2013. ‘However, the muting of opposition was also due to the influence of the Labour Party and trade unions, which contained protest and channelled anti-government anger down institutional routes from 2009 to 2011.’ (p30). These organisations did indeed push anger down the road of inevitable failure, and yes, they were betrayed, but how was this possible?

One contributor notes that by late 2013 ‘it is difficult to overstate the feeling of exhaustion and disillusionment’, with the radical left ‘comprehensively defeated on the one anti-austerity struggle they’d seriously fought – household taxes.’ The ‘public mood was judged sullen but compliant’ and was successfully ‘blackmailed’ into voting yes to the EU’s fiscal Treaty in 2012 ‘even though this treaty restricted the possibility of future government spending” (p 40-41)

I wrote about this result at the time, noting that: ‘At 60 per cent Yes against 40 per cent No there is no room for doubt. It is a decisive endorsement of government policy and a mandate for further cuts and tax increases. The result should not have been unexpected given the political forces ranged in support of the Treaty, the support of big and small business, the failure of the trade union movement to oppose it and the inevitable support of the mass media. In the general election last year the Irish people voted by a large majority for a new government in no important way different from the previous one and with no claim to pursue significantly different policies.’

I also noted that ‘Austerity isn’t popular despite the vote and never will be. Even the Yes campaign was under instructions not to celebrate its victory . . . In October last year when the Austerity Treaty was originally being negotiated an opinion poll recorded 63 per cent opposed to it with only 37 per cent supporting.’ I noted that some people had changed their minds or perhaps did not have the confidence to follow through on their opposition. This might have united around the demand to repudiate the debt taken on by the state on behalf of the banks and their bondholders, but this also meant opposition to the Troika upon whom the state had become reliant. It also meant opposition to the administration in the US, even though its Secretary to the Treasury Timothy Geithner thought it was ‘stupid’ to guarantee the banks liabilities.

I wrote a number of blogs on the issue of repudiating the debt here, here and here, and the disastrous and ‘stupid’ decision to bail out the bondholders in the first place. Doing so was a real political challenge and required an alternative that didn’t exist. Without this the failure of the opposition to austerity was inevitable, even if the question of the debt was only one element of the necessary political alternative.

Where the book completely fails is the neglect of what the political content of the alternative might have been, although this is revealing. In recording the activity of the left its non-appearance reflects the absence of this in the anti-austerity movement as a whole and the failure to win any significant section of it to a socialist perspective.

The same contributor noted above goes on to say that at a later time ‘A proper balance sheet would recognise how the Labour Party and the aligned section of the union movement were rendered powerless to influence or sidetrack the anti-austerity movement.’ (p 42). He points to the drop on the Labour vote from 19 per cent in the 2011 general election to 7 per cent in the 2014 local elections and the ‘victory for left-wing independents and Trotskyist parties alike.’ (p 43)

He argues this was possible because in 2014 100,000 marched against water charges in October followed by 150,000–200,000 in November and 80,000 (in Dublin alone) in December in what was ultimately a winning struggle. We have already noted the limp role that was expected of the trade unions and political parties in the campaign in the previous posts but the argument that the Labour Party and trade union leaders could not divert the campaign is correct.

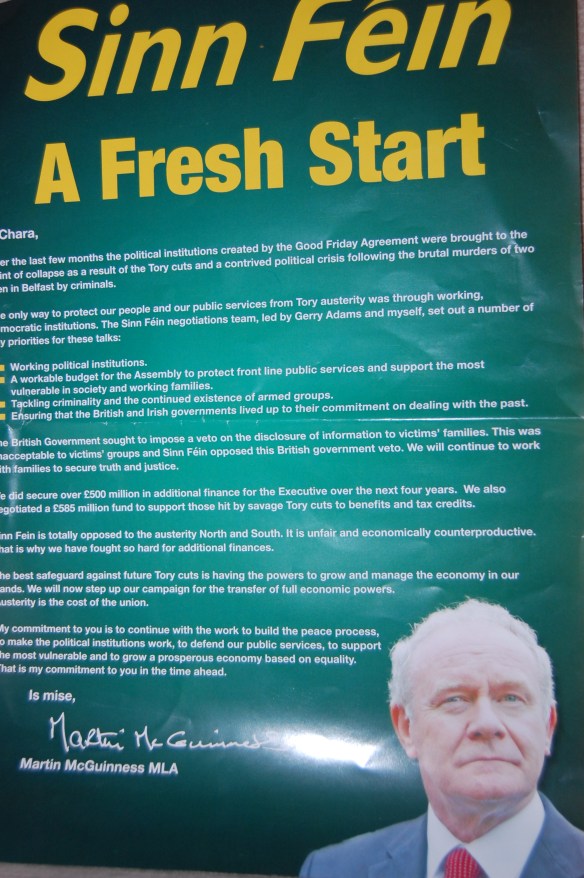

It won because it was a community campaign based on mass protests, blocking the installation of water meters and non-payment of bills. Independents and left wing candidates benefited from their role in the campaign which also distinguished itself by exposing the equivocating role of Sinn Fein. Despite the political weaknesses of the campaign that we noted previously its tactics were able to beat the counter-measures of the government where the previous campaign against household charges could not.

The campaign proved that individual campaigns, given the right circumstances, could defeat particular austerity measures even where the wider offensive was continued successfully. It should be recalled that the water charges campaign took off almost a year after the state exited the Troika bailout programme. It is also worth recording again the failure to draw the right political lessons as the trade union official who contributed the chapter on the campaign finishes his story by endorsing the statement by ‘one of the world’s greatest authorities on water’ that:

‘The Irish system of paying for water and sanitation services through progressive taxation and non-domestic user fees, is an exemplary model of fair equitable and sustainable service delivery for the entire world.’ (p 61)

In fact, the Irish water industry was wasteful and inefficient and state ownership is neither democratic nor socialist. For this, workers’ cooperative ownership or the demand for workers’ control would have been necessary but the Irish left, like so much in the rest of the world, have become habituated to statist views of socialism that Marx repudiated but that have become entrenched through the domination of social democracy and Stalinism over the last one hundred years.

With such a political platform the problem of the state being the solution, when the solvency and policy of the state was the problem, was once again avoided because doing otherwise would raise the question of ownership and control that would show the platform’s inadequacy.

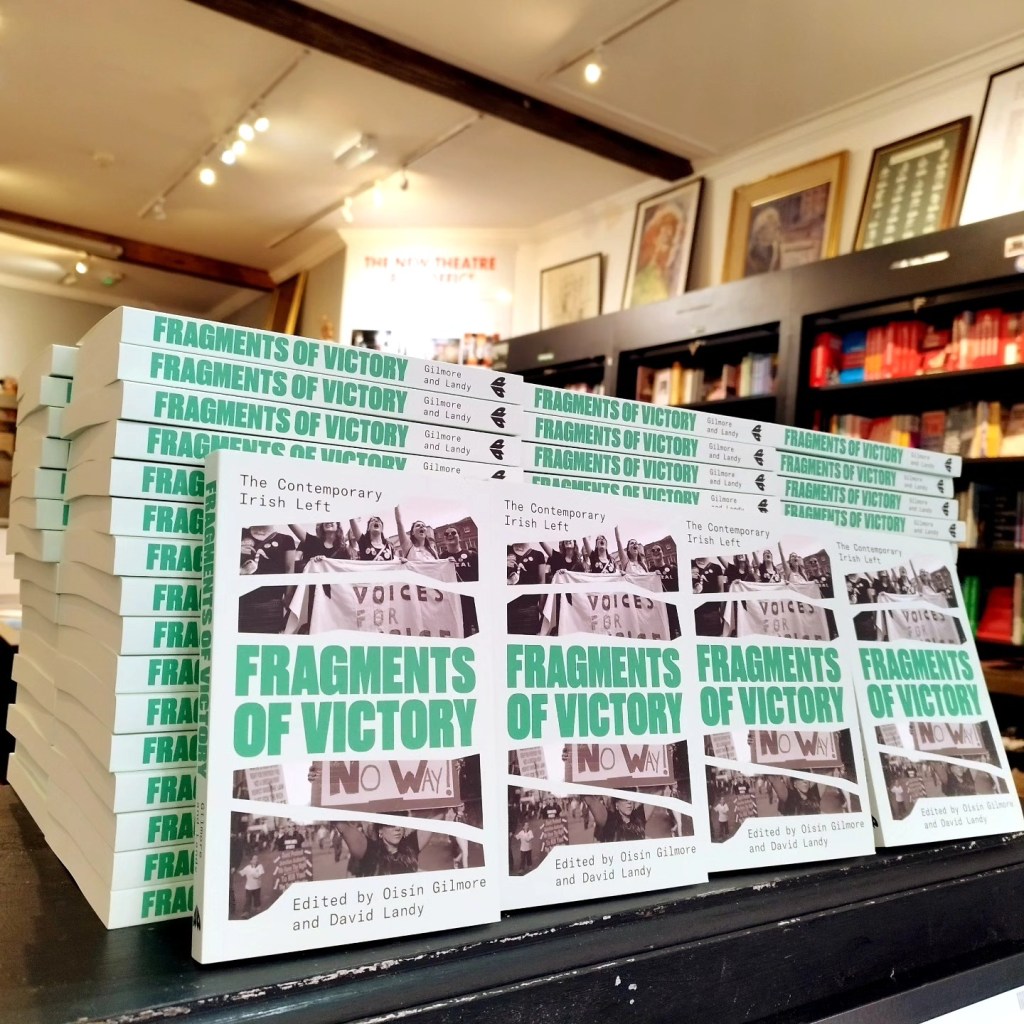

The main victory in Fragments of Victory was thus necessarily limited and could not be a springboard to address the many deficiencies of the resistance identified in the book. These included the failure ‘to build lasting political and social institutions’ and ‘no lasting form of working-class self-organisation.’ Reliance on capitalist state ownership as ‘an exemplary model’ illustrates why a problem could not be addressed: that ‘the steps between the current situation and the long-term goal of socialism are less clear than ever before.’ (p192)

The view that the trade union bureaucracy was ‘rendered powerless to influence or sidetrack the anti-austerity movement’ is therefore only partially true. The politics of the bureaucracy, and of the Labour Party, were not challenged by a wider political alternative and the much-trumpeted militant tactics of the campaign were no substitute for it.

back to part 4

Forward to part 6