Reading ‘Fragments’ I was reminded of the statement by Marx that ‘We develop new principles for the world out of the world’s own principles. We do not say to the world: cease your struggles, they are foolish; we will give you the true slogan of struggle. We merely show the world what it is really fighting for, and consciousness is something that it has to acquire, even if it does not want to.’

Fragments sets out to record the struggles of the Irish left (in the Irish state) over the past few decades so that the reader can form a view on its successes and failures. In doing so we can apply Marx’s prescription and determine to what extent it shows the left ‘what it is really fighting for’ so that it can be conscious of the lessons that should be learned.

There are some obstacles in the way, including the variety of authors with different viewpoints although an introduction and conclusion is meant to summarise the results. The major problem is the definition of what it means to be ‘left’. In the introduction Sinn Fein and the Green Party are listed as left even though the major theme of the book is the response to the implementation of austerity following the collapse of the Celtic Tiger and the consequent bankruptcy of the State.

During this period Sinn Fein presided over austerity while in a coalition government with the DUP in the North, while the Green Party entered into a coalition with Fianna Fáil in 2007 that bailed out the banks and inaugurated widespread cuts in social welfare and wages.

As part of the relaunch of Stormont in 2015 the ‘Fresh Start’ agreement committed the parties, including Sinn Fein, to reducing NI civil service staff numbers: ‘Between April 2014 and March 2016, the NICS is set to reduce headcount by approximately 5,210 and between April 2015 and March 2016 a further 2,200 will exit from the wider public sector.’ The Green Party supported the bank bailout that the state could not afford, which resulted in the intervention of the Troika of the European Commission, European Central Bank and IMF, along with the huge austerity necessary to satisfy their demands.

Even taking account of the elastic possibilities permitted by employing a relative term such as ‘left’, it is difficult to sustain any claim that these parties are in any substantial or verifiable way left-wing. Sinn Fein was described by a comrade of mine a long time ago as containing members with left-wing opinions and right-wing politics. The party has, in the meantime, fully confirmed this judgement while in government. The Green Party began life as The Ecology Party promising ‘a radical alternative to both Capitalism and Socialism’ but in office twice it has displayed no alternative to capitalism and therefore no alternative to socialism.

Looking at political struggle through the lens of ‘left’ versus ‘right’ has therefore the potential to obfuscate as much as it clarifies. A more illuminating approach is to set out the class nature of the politics of a political party and to explain why different parties with generally similar class natures have the politics that they do, even if they have different colouration.

Thus, as a nationalist party, Sinn Fein is a petty bourgeois party that considers the Irish people as one, with any class distinctions completely secondary and subordinate to the interest of the nation and its state, which can represent the true interests of all the people simply because of their nationality. The Green Party claimed at its birth to have a radical alternative but also rejected a class approach through its largely petty bourgeois base and ideology. It confirmed its class character by its members enthusiastically joining Fianna Fáil in government (voting 86% in favour) and by its commitment to the banks and austerity.

It might appear difficult to assign a class identity to some parties, and any classification has to be justified, but this is precisely the point of identifying the class nature of the forces involved. As petty bourgeois parties, both Sinn Fein and the Greens have imposed austerity on workers while espousing radical rhetoric. Calling them left is an attempt to obscure this and works to introduce doubt that they will not always fall on the side of the capitalist class in a struggle.

Fragments demonstrates this repeatedly, even when making secondary observations, for example that individual members of Sinn Fein were active in the Campaign Against the Household and Water Taxes but that the party was not: ’This form of partial (non-)commitment proved to be the defining feature of Sinn Fein’s approach to most political struggles of the time.’ (p37)

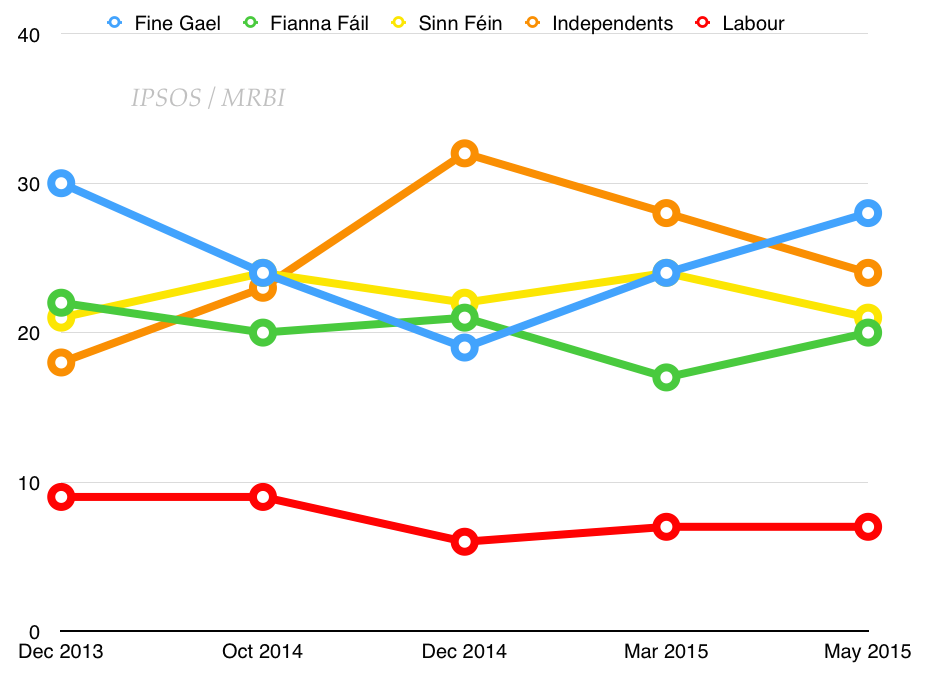

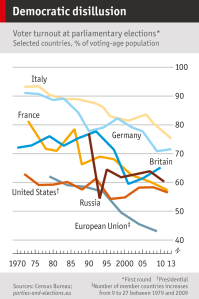

Approaching politics this way allows us to make judgements of other ‘left’ parties such as the Labour Party and Social Democrats etc. and permits an understanding of their behaviour during this period. While the Labour Party paraded its ‘Labour’s Way’ as resistance to ‘Frankfurt’s Way’ while in opposition, it had no alternative to austerity when in government. The doubling of its vote in the 2011 general election was a prelude to its consequent decimation in the next one. ‘Labour’s Way’ didn’t become Frankfurt’s Way’, not having an alternative meant it always was.

Was the 2011 vote for Labour therefore a victory for the ‘left’ and was its subsequent decimation a defeat? Did those who voted Labour in 2011 make an advance in consciousness or do so by deserting it in 2016? Or were they just registering disappointment and resignation?

Fragments offers the view that despite Labour delivering austerity when in office ‘the new government retained a huge amount of goodwill . . . the crisis was clearly not their fault and . . . the harsh austerity measures they took were seen as both forced by the Troika and, while painful, necessary’, while ‘the ‘honeymoon lasted for much of 2011 . . .’ (p31) So, were these views completely discarded when the Labour Party was dumped out of office? Was there any real advance in consciousness of an alternative when it happened? Is roping the Labour Party into ‘the Left’ clarifying either history or the future?

Today, all these parties are allied in supporting Catherine Connolly for the post of President with the additional enthusiastic support of People before Profit and Solidarity. The latter’s politics are supposed to be based on the view that existing power in capitalist society does not come from parliament but from the permanent state apparatus and the economic and social power of the capitalist system, yet they promote the idea that election to a post that is admitted not only to be without power, but forbidden to exercise any, would be a major advance.

Paul Murphy, People before Profit TD, states on Facebook that ‘this is a rare opportunity for the left to come together, and elect a voice for workers, for women and for neutrality. Change starts here.’ This is a left that includes all the parties above that have been tried and tested.

In doing so all sorts of illusions in the role of bourgeois politics and institutions; about the ability of one person to represent the nation, and all the people within it; because of a one-off vote, and of the way ‘change’ can be made, are strengthened against an alternative view that real change comes from the organisation and struggles of the working class itself.

Are such views ‘Trotskyist’, as Paul Murphy’s organisation is called in the book? Or is this term used because that is just how it is usually described, or should such a designation not require some comparison of its political practice to a reasonable account of what Trotskyism is? The umbrella term of ‘left’ addresses these questions by rendering them unimportant, and this is a problem.

To anticipate one message of this review; Fragments provides enough testimony to show that a different approach is necessary and that an alternative is required to the illusion that there is a ‘left’ that should be united to advance the cause of the working class.

It demonstrates, in its own way, that only a class analysis can explain events, including the actions of the state, why it succeeded in imposing austerity and why the resistance to it was unable to rise to the challenge. Explaining all this in terms of whether certain actors, institutions or policies were ‘left’ or ‘right’ is hopeless not only because of the vagueness of the terms but because all of these acted out of material interests, as they perceived them, and these in turn were based on objective factors that were fundamentally determined by class relations.

Forward to part 2