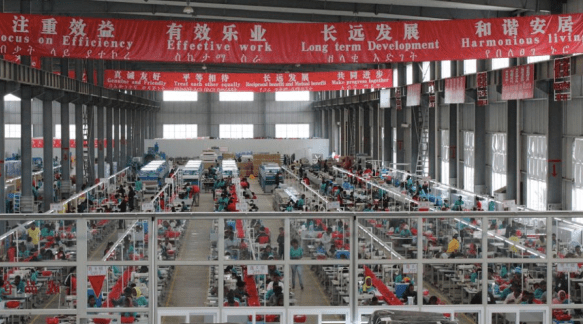

Marx states in ‘The Communist Manifesto’: ‘In proportion as the bourgeoisie, i.e., capital, is developed, in the same proportion is the proletariat, the modern working class, developed . . . Modern Industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalist. Masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, are organised like soldiers. As privates of the industrial army they are placed under the command of a perfect hierarchy of officers and sergeants . . . The more openly this despotism proclaims gain to be its end and aim, the more petty, the more hateful and the more embittering it is.’

‘The proletariat goes through various stages of development. With its birth begins its struggle with the bourgeoisie . . . At this stage, the labourers still form an incoherent mass scattered over the whole country, and broken up by their mutual competition. If anywhere they unite to form more compact bodies, this is not yet the consequence of their own active union, but of the union of the bourgeoisie, which class, in order to attain its own political ends, is compelled to set the whole proletariat in motion, and is moreover yet, for a time, able to do so.’

‘. . . but with the development of industry, the proletariat not only increases in number; it becomes concentrated in greater masses, its strength grows, and it feels that strength more . . . The growing competition among the bourgeois, and the resulting commercial crises, make the wages of the workers ever more fluctuating. The increasing improvement of machinery, ever more rapidly developing, makes their livelihood more and more precarious; the collisions between individual workmen and individual bourgeois take more and more the character of collisions between two classes. Thereupon, the workers begin to form combinations (Trades’ Unions) against the bourgeois; they club together in order to keep up the rate of wages; they found permanent associations in order to make provision beforehand for these occasional revolts.’

‘Now and then the workers are victorious, but only for a time. The real fruit of their battles lies, not in the immediate result, but in the ever expanding union of the workers. This union is helped on by the improved means of communication that are created by modern industry, and that place the workers of different localities in contact with one another. It was just this contact that was needed to centralise the numerous local struggles, all of the same character, into one national struggle between classes. But every class struggle is a political struggle.’

‘This organisation of the proletarians into a class, and, consequently into a political party, is continually being upset again by the competition between the workers themselves. But it ever rises up again, stronger, firmer, mightier.’

‘Altogether collisions between the classes of the old society further, in many ways, the course of development of the proletariat. The bourgeoisie finds itself involved in a constant battle. At first with the aristocracy; later on, with those portions of the bourgeoisie itself, whose interests have become antagonistic to the progress of industry; at all time with the bourgeoisie of foreign countries. In all these battles, it sees itself compelled to appeal to the proletariat, to ask for help, and thus, to drag it into the political arena. The bourgeoisie itself, therefore, supplies the proletariat with its own elements of political and general education, in other words, it furnishes the proletariat with weapons for fighting the bourgeoisie.’

‘Of all the classes that stand face to face with the bourgeoisie today, the proletariat alone is a really revolutionary class.’

‘The advance of industry, whose involuntary promoter is the bourgeoisie, replaces the isolation of the labourers, due to competition, by the revolutionary combination, due to association. The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers.’

Marx goes on to set out the tasks of the working class revolution, which involves ‘the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.’ This revolution is not an eschatological thunderstrike out of the blue that suddenly transforms the world but a juncture arising within existing society through the development of its contradictions.

As a conscious process of real people, it cannot be the outcome of impetuous and spontaneous apprehension, but must arise from the considered and passionate commitment of the vast majority of the working class, arising from the history and development of their struggles as a class.

We can note at least three aspects of what Marx said that has obvious relevance to today. The first is ‘the growing competition among the bourgeois’, which now takes place between previously inconceivably large corporations that span the globe that makes this competition an international phenomenon. This both unites the interests of the world working class and divides it according to the strength of the capitalist system and political weakness of the working class.

The second is the the improved means of communication that can help ‘in the ever expanding union of the workers.’ We no longer need to merely read about wars but have daily, if not hourly, video coverage of its barbarity in Gaza and Ukraine. What the working class movement has failed abysmally to do is to create its own international media, which remains in Lilliputian proportions in comparison to that of the bourgeoisie.

Through this media the bourgeoisie is compelled to appeal to the proletariat, to ask for help, and thus, to drag it into the political arena. Hence the bias in coverage of the genocide in Gaza and the war in Ukraine. Unfortunately again, we see the weakness of the working class movement that is happy to wallow in the lies about the imperialist character of the proxy war in Ukraine and line up behind its own ruling class. The very saturation of the media allows those comfortable in this position to have their deception confirmed again and again. A working class media would at least allow a wider source of information and debate, although again, such is the degeneration of much of the current left that petty bourgeois moralism is employed to silence critical voices.

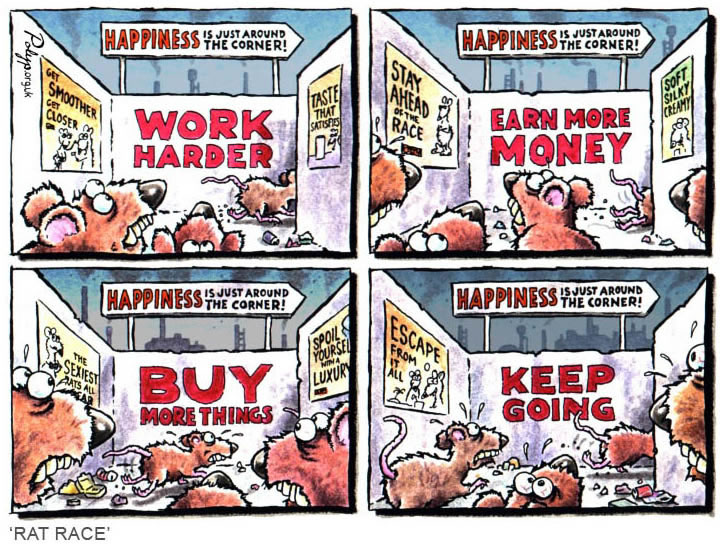

In previous posts, we noted one result of such moralism in the call to hate capitalism more as a spur and guide to action. We argued in response that a revolution conceived out of ‘negativity’ and ‘hate’, even if it is born out of oppression and exploitation, is utterly insufficient. Such a view faces the problem of how such a social revolution could become the long-term goal of the working class and could be achieved by it.

Miéville, for example, can say that ‘capitalism is unbearable and yet, mostly, it’s borne’, resulting from the success of ‘capitalist-realist common sense that it’s impossible, even laughable, to struggle or hope for change.’ In part he puts this down ‘to a deliberate ruling-class propaganda strategy to discourage any belief in any such possibility’, but ‘also, at a base level, because it’s so difficult to think beyond the reality in which one has been created, lives and thinks now . . . conditioned as we are by existing reality, we cannot prefigure or simply ‘imagine’ such radical alterity.’

The result is that ‘it’s beyond our ken – we can only yearn for it, glimpse some sense of betterness out of the corner of the eye.’ (A Spectre Haunting: On the Communist Manifesto, p 89)

Such is the idealist view of the possibility of social revolution that cannot ground the future society from the current one but sees the current in purely, or at least mainly, decisively and definitively, in negative terms for which the appropriate emotion is hate. This is why he states that ‘it’s so difficult to think beyond the reality’ when it is precisely this reality, clearly seen – not out of the corner of the eye – that provides the grounds for the social revolution, giving rise to the appropriate emotions of hope and courage derived from passionate belief in the cause, with hatred of oppression as a motivation but not determining the struggle.

This reality, according to Marx, includes the development of the forces of capitalist production and the associated relations of production that include the creation, expansion, development, organisation and growing consciousness of the working class. The prosecution of this class struggle involves the creation of a mass, political working class movement that demonstrates not only its power to increasingly defend the interests of the working class but its potential to lead to the creation of a new society ruled by it.

This alternative is built upon the conditions and circumstances of the real world and not by thinking a prefigured ‘radical alterity’ – some largely imagined future alternative – but by changing this reality through prosecuting the class struggle, ranging from the creation of democratic and militant trade unions, to workers’ cooperatives and their association with each other, to the creation of mass working class parties committed to socialism. The forces recognised by Marx that governed the development of the working class still exist today and are the grounds for the concomitant development of socialist politics.

Back to part 70

Forward to part 72

In 1921 Leon Trotsky argued that “If the further development of productive forces was conceivable within the framework of bourgeois society, then revolution would generally be impossible. But since the further development of the productive forces within the framework of bourgeois society is inconceivable, the basic premise for the revolution is given.”

In 1921 Leon Trotsky argued that “If the further development of productive forces was conceivable within the framework of bourgeois society, then revolution would generally be impossible. But since the further development of the productive forces within the framework of bourgeois society is inconceivable, the basic premise for the revolution is given.”