There are three take-aways from the Westminster election in the North of Ireland.

First, Sinn Fein continued to make progress, defending its existing eight seats, including securing bigger majorities in a number of constituencies, and making gains in others that promise two more in the future. It sealed its position as the biggest party in the Westminster elections, to rank alongside earlier local and Assembly successes, although small comfort for its failure in the local and European elections in the South a month ago.

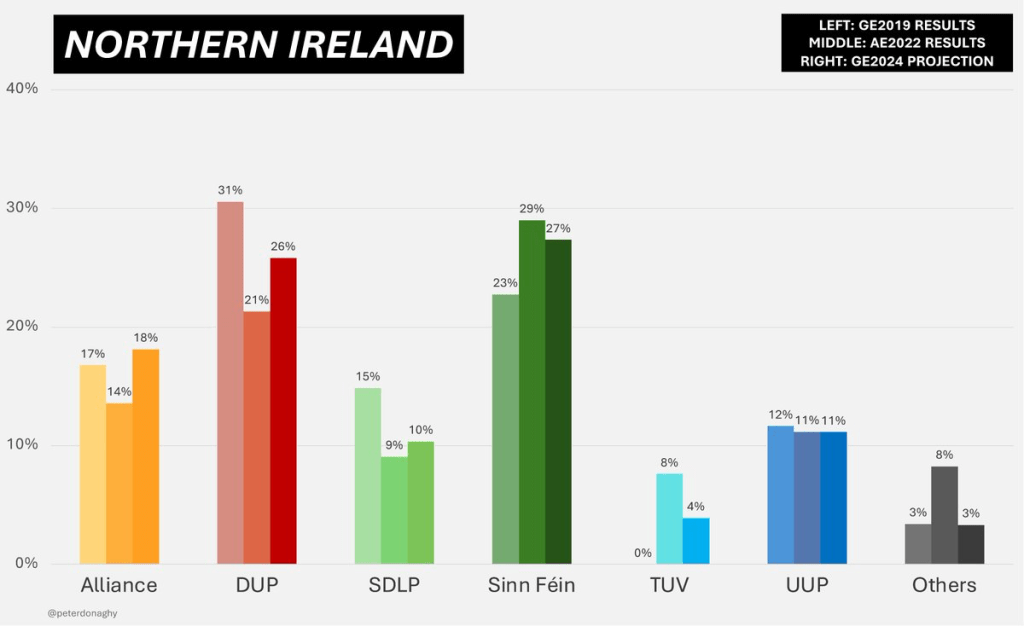

Second, the Alliance Party, as the main face of ‘others’ in the North – neither Orange nor Green, Unionist or Nationalist – lost one seat and gained another, so stood still with a small drop in the share of the vote of 1.8% on the 2019 election. The ‘Alliance surge’ has stopped surging. At 15% of the vote it does not come anywhere near marginalising the sectarian division and the basic conflict over the existence of the Northern state.

Thirdly, and most dramatically, the DUP lost three of its eight seats, very neatly lost another in East Derry and saw a dramatic fall in its majority in East Antrim. It lost from all directions: from the Alliance Party, Ulster Unionist Party and the uber-unionist TUV. In the case of the last, the defeat of Ian Paisley junior brought a smile to most faces in spite of the identity of the victor, such is the likeability of the loser. Even some of his colleagues were reported not to be too displeased. The only real bright spot was securing the seat of its new leader in East Belfast. A fall in the share of the vote of 8.5%, or a proportionate fall of 28%, is a disaster.

So what does it all mean?

Some nationalist commentary repeated familiar lines about ‘the writing on the wall’ and ‘the arrow pointing in one direction’ into the ‘inevitable future’ (Brian Feeney in The Irish News) – all references to the writing pointing to a future united Ireland. Unfortunately it’s not so simple, even for the biggest party. It won 27% of the vote, and when you factor in the lowest turnout for a Westminster election in the history of the North of 57.47%, we can readily see that 15.5% of the electorate does not a revolution make.

Over 42.5% found no reason to vote, which undoubtedly reflects a number of things, including apathy in constituencies in which a nationalist candidate hasn’t a chance, but even in the 2022 Assembly election, with a more proportionate system, Sinn Fein got 29% in a 63% turnout, or 18% of eligible voters. In this election the pro-united Ireland vote was just over 40%. If this is the writing on the wall, the wall is far away, the arrow points to a very long road, and the inevitability of a united Ireland is not quite the same as that of “death and taxes.”

Sinn Fein continues to advance in the North without any justification deriving from its now long record in office at Stormont. The latest reincarnation of devolution managed to set a budget for departments without agreeing what they were going to spend it on – what were its priorities? It spent plenty of time passing motion after motion lauding all sorts of good things with zero commitment to doing anything about them, while utterly failing to account for the public services it has been responsible for. These, such as the health service, have fallen into a crisis worse than anywhere in the rest of the UK.

For Alliance, its still second order existence testifies to the inability of the status quo to satisfy Northern nationalists or provide evidence that Unionists really are as confident that the state is as British as Finchley. Its existence at all, however, is held to define what is necessary to change this status, which is not simple growth of Irish nationalism. Convincing the ‘others’ of a united Ireland is argued as the key task for nationalism, which must include current Alliance supporters.

In this, Sinn Fein is not succeeding, in fact it doesn’t realise it isn’t even trying. It continually berates other nationalist parties, especially in the South, for not joining ‘the conversation’ on a united Ireland, and calls out the necessity of planning for it; as if talking about it brings it any closer never mind making it inevitable. It’s like being lifted by the cops who want to have a conversation with you – where you do all the talking. Where are Sinn Fein’s plans?

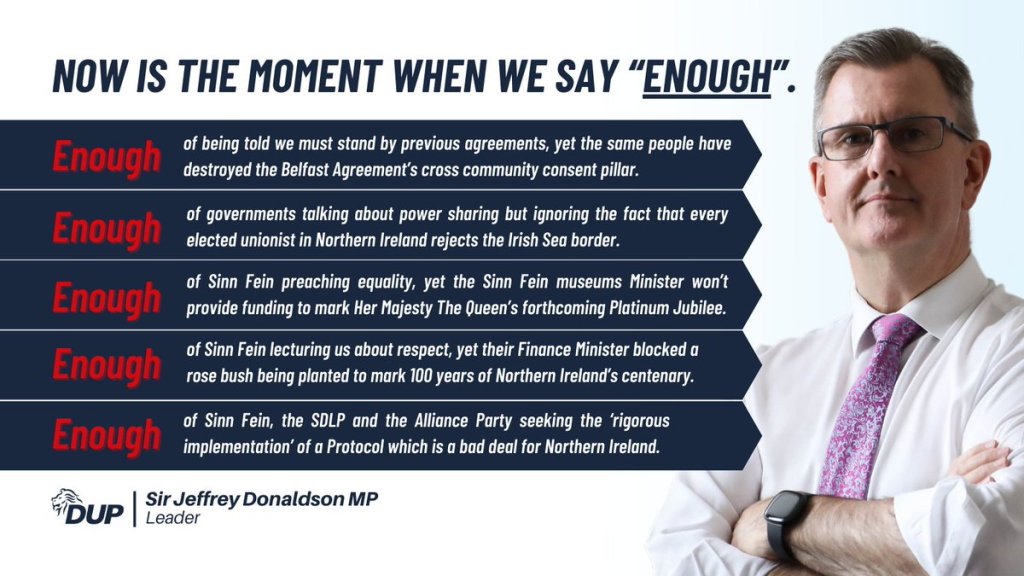

The biggest issue however, that has signalled a step to a united Ireland, has been Brexit, and it is this that has done to the DUP what it did to the Tories in Britain. While the victory of the TUV was most obviously a result of the failure of the DUP to prevent ‘the Irish Sea border’ that resulted from Brexit, it also lost because it lied about its deal with the British government that would supposedly make it disappear.

The Alliance victory in Lagan Valley was partly due to the constituency MP Jeffrey Donaldson being sent for trail on sex-offence charges, but this copper-fastened a prior loss of personal credibility as author and prime advocate for the deal. With the Brexit disaster in the background every credible opposition to the DUP looked that bit more attractive and its most vocal supporters, such as Ian Paisley and Sammy Wilson, suffered.

The local political commentator Newton Emerson noted that the DUP losses in very different directions made it difficult for the DUP to know where to pivot. This dilemma exposes the real demoralisation within unionism that sought to strengthen partition by supporting the UK leaving Europe but found itself inside a part of Ireland less aligned with the sovereign power. There is no mileage in continuing to fight it, so they won’t follow the TUV in doing so, but this means that it remains exposed to this more rabid unionism with only the old age of its leader Jim Allister as the pathetic hope of future redemption.

It can keep quiet about the whole thing and hope it disappears as an issue but there are at least three problems with this. First, its opponents will remind people, people will remember DUP stupidity themselves, and much as Keir Starmer might try to ignore it and think he can evade its worst effects, it’s not going away and neither are its effects.

A bit like the election in Britain, a thoroughly boring campaign had some more noteworthy results. The stasis, if not stagnation, in politics within the North continues but events elsewhere are not so stable and have their effect.