Hudis claims that in those countries where capitalism had been overthrown the statist ‘socialism’ that existed ‘eliminated private property and the ‘free market’ by bringing the process of distribution and circulation under the control of the state. But they did little or nothing to transform production-relations. Concrete labour was still reduced to a monotonous, routinised activity through the dominance of abstract labour. Abstract labour continued to serve as the substance of value.’ (p104)

By this is meant that social labour was fragmented and produced commodities that exchanged with each other based on the abstract labour contained within them, which was determined by the labour time necessary to produce them and not by the conscious decision on the distribution of social labour according to a preconceived conception of need and human development. Almost immediately he states that ‘instead of a surplus of products that cannot be consumed (which characterises traditional capitalism), there is a shortage of products that cannot be produced.’ (p 104).

However, this eventuality demonstrates that these societies, while not abolishing alienation – far from it – had abolished the market to the degree that meant all commodities were not produced according to the socially necessary abstract labour required to produce them and not under capitalist relations of production with a labour market producing a free working class employed by capital, either private or state. Even the creation of healthy worker’s states will not immediately end alienation, by definition the continuation of any state denotes the continuation of classes, however much their antagonism is attenuated.

Further, as Marx explained in Critique of the Gotha Programme: ‘What we have to deal with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society – after the deductions have been made – exactly what he gives to it. . . .’

‘But one man is superior to another physically, or mentally, and supplies more labour in the same time, or can labour for a longer time; and labour, to serve as a measure, must be defined by its duration or intensity, otherwise it ceases to be a standard of measurement. This equal right is an unequal right for unequal labour. It recognizes no class differences, because everyone is only a worker like everyone else; but it tacitly recognizes unequal individual endowment, and thus productive capacity, as a natural privilege. It is, therefore, a right of inequality, in its content, like every right.’

‘Further, one worker is married, another is not; one has more children than another, and so on and so forth. Thus, with an equal performance of labor, and hence an equal in the social consumption fund, one will in fact receive more than another, one will be richer than another, and so on. To avoid all these defects, right, instead of being equal, would have to be unequal.’

‘But these defects are inevitable in the first phase of communist society as it is when it has just emerged after prolonged birth pangs from capitalist society. Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby.’

Hudis is correct that it is the active role of labour that creates private property, but when he quotes Marx saying that ‘though private property appears to be the reason, the cause of alienated labour, it is rather its consequence, just as the gods are originally not the cause but the effect of man’s intellectual confusion. Later this relationship becomes reciprocal’, he leaves out the last sentence, which makes (bourgeois) private property constitutive of this alienated labour. (Marx quoted in Hudis p 61) Unlike ‘the gods’, this private property is real.

Marx says: ‘It is only at the culminating point of the development of private property that this its secret re-emerges, namely, that on the one hand it is the product of alienated labour, and on the other it is the means through which labour alienates itself, the realization of this alienation.’ C.W.3, 280;(Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, Early Writings, p 392)

“Communism is the positive supersession of private property as human self- estrangement, and hence the true appropriation of the human essence through and for man; it is the complete restoration of man to himself . . . which takes place within the entire wealth of previous periods of development. (Marx and Engels Collected Works Vol..3, p 296; Early Writings p 348).

Elsewhere Hudis quotes Marx that ‘[P]rivate property, for instance, is not a simple relation or even an abstract concept, a principle, but consists in the totality of the bourgeois relations of production…a change in, or even the abolition of, these relations can only follow from a change in these classes and their relationships with each other, and a change in the relationship of classes is a historical change, a product of social activity as a whole’ (p83 -84)

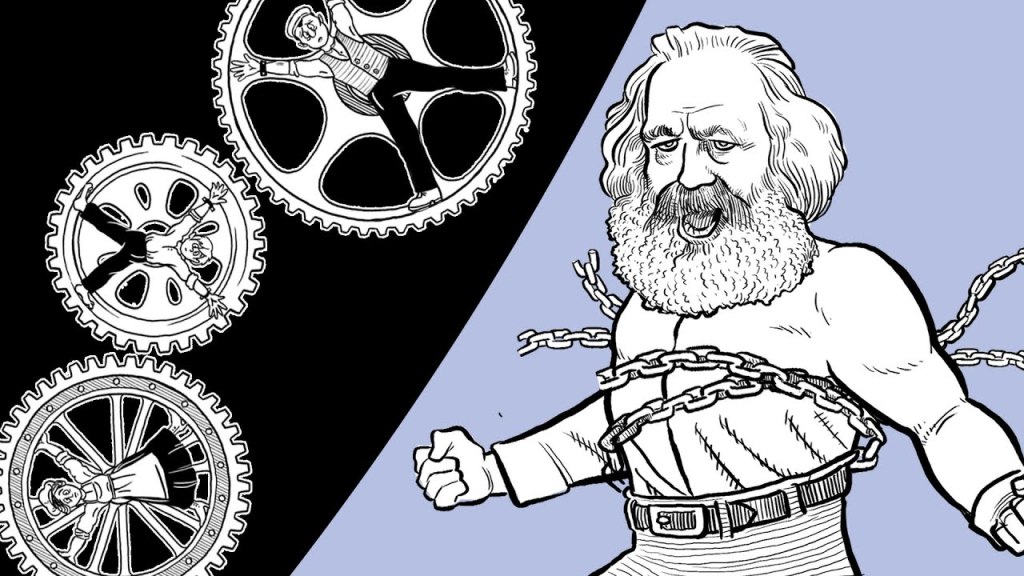

‘Marx grasps the situation as one of labour’s self-alienation in and through private property. Only if labour is grasped as the overriding moment in the alienated labour/private property complex can the conditions of a real transcendence of estrangement be established. Grounded in the alienation of labour, the immanent movement of private property necessarily produces ‘its own grave diggers’ (in the famous phrase of the Communist Manifesto). But in the dialectical opposition of private property and alienated labour the principal aspect of the contradiction then becomes the latter; hence Marx says that the fall of wage-labour and private property – ‘identical’ expressions of estrangement – takes place ‘in the political form of the emancipation of the workers’. Marx and Engels Collected Works Vol 3 p280).

Private property in its capitalist form entails the capital-wage labour relationship – the relations of production between capital and working class – from which class struggle arises, which struggle must eventuate in social revolution that makes the working class collective owners of the means of production and whose political emancipation entails overturing the capitalist state and creation of its own.

As Hudis himself notes: ‘Communism does not deprive man of the power to appropriate the products of society; all that it does is to deprive him of the power to subjugate the labour of others by means of such appropriation’.

Hudis continues: ‘In the Manifesto, Marx also writes that ‘the theory of the Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property’. It may seem that Marx has muted, if not moved away from, his perspective of 1844, in that the abolition of private property here seems to be posed not just as a mediatory stage, but as the ultimate goal. However, this would be too facile a reading. Marx focuses on the need to negate private property because it is the most immediate expression of the power of bourgeois society over the worker. Through the bourgeois property-relation, the workers are forced to sell themselves for a wage to the owners of capital, who appropriate the products of their productive activity. Without the abolition of this property-relation, the economic and political domination of the bourgeoisie remains unchallenged.’ (Hudis p82-3)

The abolition of bourgeois private property means the overthrow of the capital-wage relationship and exploitation, which are the grounds for the abolition of all classes. This objective is therefore not just required because ‘it is the most immediate expression of the power of bourgeois society over the worker’ but because, to put it in its active sense, it is thereby the most immediate expression of the power of the workers to overcome the exploitation and oppression of bourgeois society.

It is why Marx also said in The Communist Manifesto that “The distinguishing feature of Communism is not the abolition of property generally, but the abolition of bourgeois property . . . In short, the Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things. In all these movements, they bring to the front, as the leading question in each, the property question, no matter what its degree of development at the time.’

Back to part 60

Forward to part 62

Part 1 is here